Zamoyski Family Fee Tail

The Zamoyski Family Fee Tail (Polish: Ordynacja Zamojska) was one of the first and largest fee tails in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was owned by the Zamoyski family, the richest aristocratic family in Poland.[1] It was established upon the request of Crown Hetman Jan Zamoyski,[2] on 8 July 1589. The fee existed until the end of World War Two, when it was abolished by the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland, which in 1944 initiated an agricultural reform.[3]

Background

For more information about fee tails in Poland, see Fee tail in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the Kingdom of Poland and later in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, fee tail estates were called Ordynacja (landed property in fideicommis). Ordynacja was an economic institution for the governing of landed property introduced in late 16th century by King Stefan Batory. Ordynat was the title of the principal heir of an ordynacja, and each new ordynat was obliged to uphold the statute of the fee tail.

Creation

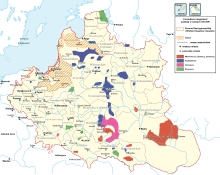

Chronologically, Ordynacja Zamojska was the second fee tail in the Commonwealth, after the Radziwiłł family estate. At the beginning, Jan Zamoyski had four villages, which he inherited from his father, Castellan of Chełmno Stanisław Zamoyski. At the moment of its creation, this estate consisted of two towns and thirty nine villages.[4] At the end of Zamoyski's life it included as many as 23 towns and together with 816 villages, it was called the Zamość State (Państwo zamojskie). Its total area was app. 17,500 km2., and it included estates both in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, and Livonia, with main centers around Zamość and Podolia. Annual income of Zamoyski was estimated at 700,000 zlotys (by comparison, the cost of Siege of Połock in 1579 was some 330,000 zlotys[5]). According to another source, Jan Zamoyski's estates generated a revenue of over 200,000 zloties in the early 17th century.[6]

The capital of the estate was established in the newly built private Renaissance town of Zamość, a private fortress of Jan Zamoyski with its own college, the Zamojski Academy, printing shop, and court. Due to its wealth, economic, and administrative independence Ordynacja Zamojska has been considered a state within a state,[7] with large parts of it covered by extensive forests.[8]

17th Century

As the statute stipulated, the estate continued to be inherited in full by the eldest son of the ordynat. Each time the new owner was approved by the king, and all financial arguments in the family were to be solved by the Polish Parliament (Sejm). In the course of the time, the arguments over the property became commonplace.

The first crisis took place in 1665 after the death of Jan Sobiepan Zamoyski, who did not have a son. Sobiepan's sister, Princess Gryzelda Wiśniowiecka (the wife of Jeremi Wiśniowiecki and the mother of King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki) regarded herself as the heiress of Zamoyski fortune. At the same time the Koniecpolski family, headed by Sobiepan's sister Joanna Koniecpolska, also demanded their share of the estate. A legal war ensued in which Joanna Koniecpolska seized the fee tail, ruling it until her death in 1672. The estate remained in the hands of the Koniecpolski family until 1674, when the Sejm ordered that the estate should be transferred to Marcin Zamoyski. Stanisław Koniecpolski disagreed with the decision and used his private army to try and prevent Zamoyski from taking control over the estate. In the end Koniecpolski gave up, as Zamoyski had the supported of the local szlachta, as well as that of King John III Sobieski.

New line of owners

Marcin Zamoyski took control of the estate in 1676, becoming one of the wealthiest landowners of Europe.[9] The fee remained in the hands of his family until its end in 1944 - 1945. Zamoyski turned out to be a skillful owner, and the property flourished under his management. In 1688 he ordered the map of the estate (Mappa Ordynacyey Panstwa Zamoyskiego), which shows that the fee included nine towns (Zamość, Goraj, Janów Lubelski, Kraśnik, Krzeszów, Szczebrzeszyn, Tarnogród, Tomaszów Lubelski, and Turobin, as well as 157 villages. Furthermore, Zamoyski owned glass and iron works, breweries, mills and other enterprises. Marcin Zamoyski closely cooperated with King Sobieski, which resulted in him being nominated the Voivode of Lublin Voivodeship.

18th century

In the early 18th century, the estate suffered destruction during the Great Northern War. After the conflict, its owners tried to rebuild the Zamość State, establishing new settlements and supporting trade. The 7th ordynat, Tomasz Antoni Zamoyski, promoted river transport, building ports along the San and the Vistula. In 1773, the 9th ordynat, Jan Jakub Zamoyski, opened a soap and porcelain plant at Zwierzyniec.

First partition of Poland (1772) divided the estate into two parts. Four towns and 39 villages remained within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, while six towns and 150 villages became part of Austrian province of Galicia. Austrian authorities confirmed legal status of the fee tail, but its division made management difficult. Andrzej Zamoyski, who was the 10th ordynat, trying to buy support of Austrian Emperor Joseph II, invited some 100 native German families to settle in the estate. In return, the Emperor in 1786 confirmed the statute of the fee tail, and its legal and territorial separation.

In the 1790s, when the Commonwealth ceased to exist, the estate's future existence depended on the good will of both Austrian and Imperial Russian courts. The 10th ordynat, Aleksander August Zamoyski, hoping to avoid punishment from the Russians did not join the Kosciuszko Uprising. Finally, after the Third partition of Poland (1795), the whole estate found itself under Austrian rule. In the late 18th century, August Zamoyski established a faience plant at Tomaszow Lubelski which employed 50 workers.

19th century

After the Polish–Austrian War, West Galicia was incorporated into the Duchy of Warsaw, and the estate was once again divided. In 1812, its capital was moved from Zamość to Zwierzyniec, as the Zamość Fortress was being transferred to the Polish government (the transfer itself was not completed until 1821, when the fortress together with the town of Zamość officially became property of the government of Congress Poland). In exchange, the Zamoyski family was given estates in Mazovia and Podlasie. In 1811, Stanislaw Kostka Zamoyski, the 11th ordynat, opened in Warsaw a public Library of the Zamoyski Fee Tail, which was based on the Zamojski Academy, closed down in 1784.

The 13th ordynat, Konstanty Zamoyski, introduced several changes to the estate. In 1833, he created the Central Office of Goods and Businesses of the Zamoyski Family, as well as General Administration Office in Zwierzyniec. Zamoyski divided the office into four departments (legal, administrative, political and economic), each with its own manager.[10] At the same time, serfdom was gradually withdrawn and replaced by money wages (15 grosz per one day of work). Furthermore, to increase profits several folwarks were rented to private owners, and the management of the forests took on a planned shape. In the mid-19th century, the estate had an area of 373,723 hectares, and its population was 107,764, with nine towns, 291 villages, 116 folwarks, 41 mills, eight breweries, seven distilleries and several other enterprises. Altogether, the profits of the fee tail were estimated at 1.4 million zlotys annually.

Following the Emancipation reform of 1861, which in 1864 was introduced in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland, the area of the estate was reduced, as well as its income, since peasants ceased to pay their feudal obligations. Nevertheless, due to skillful management, the fee tail was profitable, allowing the 14th ordynat Tomasz Franciszek Zamoyski to expand the palace at Klemensow, together with the neglected library. Among most important items kept in the library was the Codex Suprasliensis.

At the outbreak of World War One the estate was a well-functioning enterprise, with 156 folwarks divided into three keys. The fee tail had several factories, and its own narrow gauge rail line. The war devastated the estate, and further destruction was brought on by the Polish-Soviet War, when soldiers of Semyon Budyonny captured Klemensow. Altogether, the losses of the estate were estimated at 8.5 million roubles. Maurycy Klemens Zamoyski, the 15th ordynat, actively supported Poland's fight for independence, and in the 1922 presidential elections he was a candidate of the conservative parties, running against Gabriel Narutowicz. During the Polish-Soviet War, he handed his estate as a lien to the French government, to pay for the military materiel which had been provided to the Polish Army.[11]

Second Polish Republic and World War Two

In 1922, the fee tail had the area of 190,279 hectares, and was the largest estate of the Second Polish Republic. Due to poor management, its debt increased and profits decreased, so Tomasz Zamoyski sold more than 30,000 hectares of forest to the government. The estate did not became profitable until the mid-1930s, and before the outbreak of World War Two, its area was 56,199 hectares, with brickyards, sawmills, a brewery, a sugar refinery at Klemensow, and several other enterprises.

In late September 1939 (see Invasion of Poland), the estate was for two weeks occupied by the Red Army, whose units in October 1939 withdrew eastwards, leaving the estate in the hands of the Nazis. Short Soviet rule was marked by widespread looting by local peasants.[12] In the late 1939 German occupational authorities established control over the estate. The 16th ordynat Jan Tomasz Zamoyski officially remained in his post, but all decisions were taken by the Germans, who were very efficient, introducing mechanization. Soon it turned out however, that above all the Germans were interested in exploitation of the fee tail, especially its forests. It was due to efforts of the Polish officials that forests of the future Roztocze National Park were saved. During the war, the estate lost its collection of historic books, as its Warsaw library was destroyed,

End of the estate

In mid-1944, when the Red Army entered the area of Zamosc, the estate had the area of 59,054 hectares, and was a well-functioning, profitable enterprise. Its existence came to an end on 6 September 1944, when a land reform was declared by the Polish Committee of National Liberation. Soon afterwards, parts of the estate were divided between 1,208 families. The remaining land was transferred to the State Agricultural Farms, while 54,00 hectares of forests of the Zamoyski State were administered by the national government. Formally, the Zamoyski Family Fee Tail ceased to exist on 21 February 1945. The last owner of the estate, Jan Tomasz Zamoyski was imprisoned in Kielce by the Communist secret services, and the Communists stole family's treasure, hidden in a secret room at the Klemensow Castle.[13] Zamoyski himself with family was ordered to stay away from the estate, so he left to Sopot, to be imprisoned again and finally released in 1956. One of Communist agents who tortured him at Warsaw prison was Polish Jew Jozef Rozanski (Josek Goldberg), whom Zamoyski had saved from the Nazis in 1944.[14]

Ortynats of the Estate

I. 1589-1605 Jan Zamoyski,

II. 1605-1638 Tomasz Zamoyski,

III. 1638-1665 Jan "Sobiepan" Zamoyski,

IV. 1676-1689 Marcin Zamoyski,

V. 1704-1725 Tomasz Józef Zamoyski,

VI. 1725- 1735 Michał Zdzisław Zamoyski,

VII. 1735-1751 Tomasz Antoni Zamoyski,

VIII. 1760-1767 Klemens Zamoyski,

IX. 1767-1777 Jan Jakub Zamoyski,

X. 1777-1792 Andrzej Zamoyski,

XI. 1792-1800 Aleksander August Zamoyski,

XII. 1800-1835 Stanisław Kostka Zamoyski,

XIII. 1835-1866 Konstanty Zamoyski,

XIV. 1866-1889 Tomasz Franciszek Zamoyski,

XV. 1892-1939 Maurycy Klemens Zamoyski,

XVI. 1939-1945 Jan Tomasz Zamoyski.

References

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Historia Gospodarcza Polski By Andrzej Jezierski, page 40

- Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes, edited by Hannes Palang, page 77

- Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes, edited by Hannes Palang, page 77

- Ordynacja Zamojska at Wirtual Roztocze Archived February 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Sławomir Leśniewski (January 2008). Jan Zamoyski - hetman i polityk (in Polish). Bellona. p. 145.

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012

- Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes, edited by Hannes Palang, page 77

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

- Fortuna Zamoyskich kołem się toczy Wojciech Surmacz, Forbes, 28.03.2012 “Zamoyscy byli najbogatszym rodem arystokratycznym w Polsce“

Bibliography

- Tarnawski A., Działalność gospodarcza Jana Zamoyskiego. Kanclerza i Hetmana Wielkiego Koronnego (1572-1605), Lwów 1905.

- Glatman L., Sukcesorów imć Pana Ordynata Marcina Zamoyskiego spór o ordynację, Zamość 1921.

- Horodyski B., Zarys dziejów Biblioteki Ordynacji Zamojskiej w "Księga Pamiątkowa ku czci Kazimierza Piekarskiego", Wrocław 1951.

- Orłowski R., Działalność społeczno-gospodarcza Andrzeja Zamoyskiego (1757-1792), Lublin 1965.

- Orłowski R., Ordynacja Zamojska w "Zamość i Zamojszczyzna w dziejach i kulturze polskiej", pod red. K. Myślińskiego, Zamość 1969.

- red. Mencel T., Dzieje Lubelszczyzny, T. I. Warszawa 1974.

- Zielińska T., Ordynacje w dawnej Polsce w "Przegląd Historyczny", T.68, z.1, Warszawa 1977.

- Witusik A. A., O Zamoyskich, Zamościu i Akademii Zamoyskiej, Lublin 1978.

- Grzybowski S., Jan Zamoyski, Warszawa 1994.

- Bender R., Reforma czynszowa w Ordynacji Zamoyskiej w latach 1833-1864, Lublin 1995.

- Zielińska T., Poczet polskich rodów arystokratycznych, Warszawa 1997.

- Klukowski Z., Zamojszczyzna 1944-1959, Warszawa 2007, ISBN 978-83-88288-93-7