Zalužnica

Zalužnica (Serbian Cyrillic: Залужница) is a village in the Gacka valley in present-day Lika-Senj County, Croatia. It is located around the road between the market town of Otočac and the Plitvice Lakes National Park. It was likely mainly populated in the early to mid-17th century. The existing village church dates from 1753[2] and anecdotal evidence suggests it was preceded by an earlier wooden built church. A peak population was reached in the late 19th century and from there progressively reduced due to migration and war. It was almost totally de-populated in 1995 during the war that saw the breakup of the former Yugoslavia when the high majority of the population left for Serbia. A handful of old people remained in the village unable or unwilling to make the long trek. A few new people subsequently established holiday homes over the last 10 years and a few returned from Serbia. More recently, local authorities have given Roma people use of the many empty farm properties. The annual Petrovdan celebrations were re-established in the 2000s attracting people with a connection to the village from Serbia and from abroad (see 'YouTube' for films from various years).

Zalužnica | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Country | |

| Municipality | Vrhovine |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 220 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

There are many people scattered around the world who have some connection with the village resulting from the many migrations away from the village throughout its history. For the village diaspora, there are many issues in trying to find their family ties and heritage. This is reviewed in the below section on 'Ancestor Records....'.

Population

Manojlo Grbić [3] lists that in 1768 Zaluznica comprised 68 households (the author estimates a population of around 600). A German publication, https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Jahrbücher_für_slawische_Literatur,_Kunst_und_Wissenschaft, from 1847 has the population at 1,561 with 271 households (on page 91). This probably presents the pinnacle of the population. The 1848-49 upheavals in the Austrian Empire, Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire, which required intervention of Russian forces on the side of the Austrians and the subsequent migrations to Northern Bosnia (Bosnia annexed by the Austrians in 1878) and the 'liberated' Lika border lands took its toll on the village population. The 1866 book by Vinko Sabljar,[4] states 75 houses and a population of 990. A survey from 1895,[5] had the population at 1139 with 178 households (made up of the main village and the hamlets of Draga Brakusa, Čelina, Gola Brdo and Cvijanović Kuca. In the first decade of the 20th century many people left for the US with the many millions of others from Europe.[6] Subsequently, the impact of the two World Wars (death and migration), the 1960/70s economic migration to cities both in Yugoslavia and central and Western Europe reduced the total population. Ultimately, the wholesale migration of the village to Serbia in 1995 due to war resulted in the near-total depopulation of the village. According to the 2011 census, there were 220 inhabitants living in 157 housing units.[7] Based on anecdotal evidence from various visits to the village after this date, the number of permanent inhabitants is significantly lower, estimated at less than 30.

Family names and households in the village is listed by Radoslav Grujić in 1915: Agbaba - 1 household, Borčić/Delić - 1, Borovac - 20, Brakus - 46, Dorontić - 5, Grbić - 1, Grozdanić - 1, Hinić - 40, Ivančević - 31, Kosić - 6, Krainović/Krajnović - 4, Milinović - 2, Mirković - 5, Novaković - 4, Popović - 33, Srbinović/Srbjanović - 1, Srdić - 1, Uzelac - 10, Vukovojac - 12.

Where there are only 1 or 2 houses of the same surname, they are likely to be most recently settled in the village. For example, the Srdić and Grbić surnames are mainly to be found in Vrhovine. The Grozdanić name is mainly found in Ponori and associated hamlets. Borovac, Brakus, Hinić, Ivančević, Popović, and Vukovojac amongst a few others appear in the earliest Austrian army records; from at least 1756.

As many households had the same family name although not related (in living memory) the practice of giving nicknames, called 'špicnamen' (German origin) to differentiate themselves, was widespread. These nicknames originated for a variety of reasons and similarly to how surnames originated. In many cases, it referred to the given name of the head of the family at a point in time, although for the most populous surnames different nicknames evolved.

Grujić also documented some of the špicnamen: Baćini, Bekuti, Brašnari, Guslice, Kuća, Seperi, Šamendulje, Vargani aka Hinić, Čulumi, Mezani aka Ivančević (an army record in the early 1800s lists a Čulumi from Zalužnica), Dejići, Dvogroške, Sajići, Šare aka Popović, Karapandže, Keseri, Pišnjaci aka Brakus, Korice aka Krajnović.

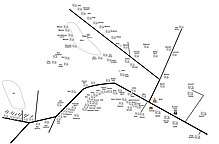

The rough plan to the right is an incomplete view of farmhouses from the 1970s, including some of the 'špicnamen'. Major exceptions are farmhouse details for Draga Brakus and the Hinić concentrated around Um.

Language

Given the relative isolation, mixed origins, neighbouring Croats who spoke a different dialect (and accent) and the influence of the ruling Austro-Hungarian state, the language used by people in Zalužnica and other nearby Serb villages developed its own character. From an academic perspective the people spoke the Štokavian dialect and over-time mixed Ijekavian and Ekavian variants in every day language, which again reflects their origin e.g. in the mainly Serbian ekavian sub-class the word for 'milk' is 'mleko' compared to mljeko in the ijekavian form. Some words in an otherwise mainly shared south slav lexicon were different e.g. the Serbian 'hleb' for 'bread' compared to Croatian 'kruh'. Some Zalužnica villagers used the slang 'krua-leba'. German words (and corrupted forms) also became inter-mingled into everyday use, influenced by the direct Habsburg rule, e.g. German 'grau' for 'grey' as opposed to the Slavic 'siv', 'šnider' for 'tailor' instead of 'krojač', 'stoff' used for 'cloth' instead of 'tkanina'. There could be some Latin-based influence, originating from close by Venetian territories on the coast or from true vlachs e.g. 'čeno' for 'dog' instead of Slavic 'pas'. The rural upland setting naturally stamped its own influences.

Surrounding area

Zalužnica sits on the eastern slope of the Gacka valley and the main pass to the Plitvice plateau from the valley. It sits around the main road running from Plitvice Lakes National Park to Otočac via Vrhovine. By car, it takes about 45 minutes to drive from the village to Plitvice and 20 minutes to Otočac. The to the west, at the edge of the village, the road splits. What used to be the Markovac country lane before 1995 is now the main road to Otočac and the next village is Podum /Podhum (Serb village). Taking the road to the south-west, the first village is Sinac (Croatian village). Otočac is the major market town in the Gacka Valley. Before 1995, it was populated by a Croat majority and large Serb minority. At the centrally located school house on the main road, a country lane runs northwards towards Doljani and Škare. Following the main road eastwards towards Plitvice, the first village is Vrhovine (high majority Serb village) about 15 minutes drive. Vrhovine is probably the highest above sea level in the immediate area ('Vrh' literally means the 'top' or 'peak'); 700m above sea level compared to Zalužnica's 500 m. Vrhovine has a railway station. While there were a few households off the beaten track there are was no other settlement between the villages; to the immediate south, south-east and north-east are mountain peaks. Beyond the schoolhouse and church along the main road is a limestone cavern and underground river, which until WW2 was the main drinking water supply for the village. A number of common use wells were dug around the village that tapped into the same underground water supply. Farmhouses are predominately located along the main and Škare roads at the base of large hills.

Farming

Farming in Zalužnica was a matter of self-subsistence made difficult by the limestone geology and rough terrain. The mainstays of the average farm was sheep, cattle, pigs, grains, and potatoes. Plum orchards were a very important resource from which the local spirit called Šlivovic (otherwise rakija) was made. The winters are typically harsh, and the summers are hot. Until the early 1960s, most work on farms was manual throughout the year using bullocks/ox (or a few families who could afford to keep horses) as the main power source for heavy farm work. By the mid-1970s, farming became almost fully mechanised. Farms were small with many small fields scattered around the village resulting from historical family inheritance customs, which further limited the scope for larger farmsteads. For those farms away from the main road electricity was only connected in the late 1950-60's and piped water in the 1970-80's.

History

From its establishment due to conflict, the village and its people continued to be moulded by almost constant conflict throughout its history. The main exceptions were the economic migration to the US in the early 1900s and the relative prosperity of the 1960-1980's. It is therefore no surprise that village life was ended during conflict in 1995.

The regular occurrence of war and conflict has seemingly destroyed most social and communal documents. The church records are missing. Most readily available documentation provides small snippets of tangential information; Austro-Hungarian Army records (18th to 20th century), 19th and early 20th century ecclesiastical and population surveys, and the Ellis Island information (1890 to 1920).

Pre-1300s The presence of a notable opening at ground level to an underground river and caverns would have likely attracted people through the ages. In addition, the narrow pass at the eastern part of the village provides one of the few access points from the Gacka valley to the extensive lakes system of Plitvice.

Beyond Draga Brakus towards the Vatinovac peak is the Bezdanjača cave[8] where around 200 burials were discovered dating to the middle to late Bronze Age (1500-750 BC).

While there are Roman remains in Lika, there's nothing of note within the area of the village. Vrhovine had been a Roman settlement, called Arapium.

From 1300, Otočac became part of the Frankopan family estate, which probably extended to include the area that became Zalužnica.

Prior to the Ottoman incursions, there was possibly a Croatian settlement. Fras[9] claims that in the general vicinity of the village there are traces of church ruins of which nothing is known other than its name of Sv.Mihovil. (Note: The reference to Fras is taken from a 1988 Croatian translation and not from the original book.).

The name of the village evolved. A history of the Otočac regiment by Franz Bach,[10] mentions the village in the mid-18th century as "Sct Peter (Založnica)", for example on page 51. The book by Vinko Sabljar lists the village as "Založnica (Zalužnica, Sveti-Petar)". The name refers to the church in the village, its full title 'Sveti Petar i Pavao' (St Peter & Paul).

Ottomans

In the aftermath of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 the Ottomans pushed northwards further into South Eastern Europe, progressively taking control of Serbia, Bosnia, and Dalmatia hinterland. Venice maintained control of key cities on the coast. The spread of the Ottoman Empire forced large numbers of Slavic and other peoples into Austrian and Hungarian territories. The limited record in Venetian, Austrian and Hungarian lands report the arrival of people variously called Rascians, Serbs, and Vlachs from the 1500s.

The Ottoman decimation of the Croatian nobility in 1493 at the Battle of Krbava Field in southern Lika caused major depopulation in Lika, people fleeing further northwards. The Ottomans settled Lika establishing a new border. The aforementioned possible Croatian settlement in the area of Zalužnica likely disappeared around this time.

Through the 1500s and particularly following the Hungarian defeat of 1526 at the Battle of Mohacs the Ottomans extended their territory. In Lika, this reached immediately to the south of Otočac. From around the 1520s, it saw the emergence of the Uskoks. Catherine Wendy Bracewell's 'The Uskoks of Senj', describes the nature of this borderland, of skirmishes and raids.

In 1553, Emperor Ferdinand granted this military border full civil and military authority to a general officer, to the displeasure of the Croatian nobility and Hungarian Diet. The regular and ongoing antagonism of the Croatians towards the Serb communities in the Military Border (Krajina) over the subsequent centuries seemingly stems from this time. Orthodox peoples were encouraged by the Austrian authorities to settle the de-populated borderland as they provided the means to defend the border without the high cost of deploying its own forces. These settlers were soldier/farmers and became known as Grenzers ( graničari - literally 'border guards'). From around 1600 a large number of Serbs arrived in Croatia and Slavonia and were granted various rights including freedom of religion by the Emperor. From this time Krajina came under the direct control of the Austrian authorities.

At around the same time, the Uskoks were forced out of Senj by Austrian authorities at the behest of Venice. Some were settled around Otočac. A local Austrian official reports the arrival of 'Walachen' around the Otoćac area in 1611 ('families and their animals'). Although this could be confused for the Uskoks, the official further reports that they were fleeing the Turks.

In November 1630, the Austrian Emperor announced the so-called Statuta Valachorum, establishing the status of settlers in the Austrian Empire. The Croatian nobility on regular occasions made efforts to remove Austrian control of Krajina, subsume the settlers into their feudal property and convert the 'schismatic' Orthodox population to Uniat or Catholicism. On more than one occasion this led to rebellion, for example, the 1728 major uprising in Lika.[11] The Austrian authorities were forced to re-assert the rights of the Grenzers fearing the loss of their loyalty and therefore an important fighting force.

On the other side of the border, the Ottomans resettled Christian subjects form their southern conquered lands into Northern Bosnia and Southern Lika, notwithstanding the settlement of Muslim converts from Bosnia and Ottomans. The intent was to create their own buffer zone around the border.

Manojlo Grbić [12] wrote in 1890 that in 1658 people settled the Gacka valley who came from Usore in Bosnia and that in 1890 those people were Serb communities of Zalužnica, Škare, Doljani (etc.). However, there is no reference to the source of this information.

While the border remained roughly in the same position, Lika continued to be subject to population migration and turmoil until the early 18th century. This reached a peak in the late 17th century after the Ottomans failed for a second time to conquer Vienna in 1683 (Great Turkish War). In Lika, the Grenzers forced out the majority of Ottoman and other Muslim settlers. Lika was re-settled from the north and any remaining Muslims (Slavic or otherwise) converted to Christianity. For a short period, there was again a significant de-population of Lika.[13]

Following the Ottoman defeat, the Austrians encouraged the Slavic population in Serbia and Bosnia to rise against the Ottomans. It failed, resulting in the (Great Migrations of the Serbs) of 1690, to mainly eastern Krajina (Slavonia) and Hungary, and to a lesser extent into western Krajina. This major upheaval caused further population migration into Lika.

While the threat of Ottoman invasion had receded considerably since the early 18th century, the Grenzers continued to be involved in protecting the border with repeated incursions until the mid 19th century. The Austro-Turkish War (1788–1791) saw the last major conflict between the empires. In Lika more lands were taken from the Ottomans in the area around Korencia after this conflict. Austrian army records describe land given to local fighters for their efforts and included grenzers from Zalužnica, pre-empting migration to Bosnia some 80 years later.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there were multiple years of failed crops and famine. This again prompted population turmoil across Lika. The revolutions across the Austrian Empire in 1848-49 was a further major upheaval due to the losses of grenzers in the various failed efforts by the Austrians to regain control. With Ottoman power dwindling in Bosnia and its annexation in 1878 by Austria, further migration occurred from Lika to Northern Bosnia occurred.[14] It is therefore unsurprising of DNA links between people in the Gacka Valley and Korenica areas with those in Northern Bosnia.

Around this time Zalužnica people moved to Lika lands depopulated of Ottomans. There is anecdotal evidence that people from the Gacka Valley moved to the area that became the village of Turjanski. First farmed and grazed during summer months, around the 1870s people began to settle. This included at least one of the Hinić families from Zalužnica believed to be the Šegotini. A quick review of Turjanski surnames (before 1995) shows a very close match to Zalužnica, Doljani and Škare surnames.

The ethnicity of the peoples who settled and re-settled Lika has been debated extensively, but in effect it is of little consequence as after quick time these peoples assimilated and identified themselves as Orthodox Serbs, becoming the majority population across the Krajina.

The turmoil of the revolving cycle of war, raiding, migration, and settlement for around 300 years in Lika can be viewed simplistically as solely attributable to the Ottomans. While Ottoman aggression northwards was the cause of initial migrations, for much of this period the political machinations of Austrian foreign policy (and many non-Ottoman wars), Hungarian territorial claims, the Croatian nobility's efforts to hold onto feudalism, and Ottoman foreign policy (and many non-European wars), were the primary factors in the course of events that moulded Lika and therefore the people of Zalužnica.

The Regiment

The settlers were soldiers first and farmers second, which ensured their status as freemen. The protection of the border dominated their lives and the settlers together with the Croatian populace in Lika progressively established themselves as a critical fighting force for the Austrian Empire.

This was formally recognised from 1746 when the Grenzers were organised into the Austro-Hungarian Army under a number of regiments. In western Krajina, Karlovac (Karlstadt) became the primary headquarters with regiments based in Otočac, Gospić, Ogulin and Slunj Grenz infantry. The Otočac regiment was initially called the “Karlstädter Otocaner Grenz-Infanterie-Regiment” and consisted of 4 battalions of around 5,000 men. The Otočac regiment recruited from all communities across coastal, central and northern Lika.

As the relative threat of the Ottomans retreated, the Grenzers became employed in the Empire's other wars in central Europe e.g. the Seven Years' War. With the Grenzer power base beginning to be perceived a problem by the Austrian authorities and following a Grenzer rebellion in 1800, the numbers were significantly reduced from around 57,000 to 13,000 together with various attempts to re-organise them. The regular wars with the French in the late 18th century and early 19th century ensured that the Grenzers remained an important force.

The Otočac regiment was on the battlefield against Napoleon. On defeating the Austrians, Lika and its regiments came under Napoleonic control for a short period from 1809 to 1814. Battalions from the various Lika regiments were part of the French army that invaded Russia. Following Napoleon's demise, Lika returned to Austrian control.

The extent of the regiment's role in everyday life is indicated by 'births, deaths and marriages' records in the mid-19 century. For example, church records for Vrhovine from 1856 show that for even births the regiment and company of the father is documented. For marriage records, the regiment and company of both the groom and bride's households is documented. Various Otočac Regiment records, from 1772 to 1819, document Zalužnica soldiers including; Borovac, Brakus, Hinić, Invačević, Kosić, Popović, Uzelac, and Vukovojac.

The last vestiges of the Krajina were removed in 1881 by Emperor Francis Joseph. Ahead of this the Otočac regiment, in 1880, was re-designated the 79th K.u.k. Infantry Regiment "Otocaner Graf Jellacic, which by in large remained intact until the end of WW1.

USA Migration

Towards the end of the 19th century, a trickle of individuals travelled to the USA seeking work and a better future, as millions of others did from Europe for the same reasons. From the turn of the century, the numbers leaving Zalužnica for the USA ramped up significantly. The immigration records for New York (Ellis Island) and other ports of entry reveal a pattern of specific villagers travelling to a specific town/city in the US, built on the back of the first few who travelled there. Zalužnica immigrants tended to favour Cleveland, Ohio. The immigrant stories are wide and varied. Some settled permanently in the US, some returned after a few years with enough money to make a difference to their families and inevitably became embroiled in WWI. The vast majority obtained manual work in factories (primary production such as steel making) and mining and of these many died or were significantly injured in industrial accidents.

While mostly men made the trip, the records include women and children, both together and separately. Surnames were changed, purposely and by accident. Changes ranged from 'no change', minor changes to improve pronunciation in an English speaking world and adoption of surnames that bore no resemblance to the original. Some were registered name changes while many just happened. Many 'disappeared' and only in the 2000s they have started to 'reappear' through DNA testings, their descendants discovering previously unknown lineage to Lika and their actual family name.

World Wars

Leading to World War I the Otočac regiment was designated k.u.k Infanterieregiment Graf Jellaèić Nr.79. The 'Nr.79' was sent to the Serbian front at the start of WWI, with many of the A-H Army's Serb soldiers becoming POWs in Serbia. At the start of 1915, it found itself on the Galician front, through the Carpathian Mountains, fighting against Russian forces and suffering heavy losses through 1915. Many were taken as POWs. On Russia exiting the war in 1917 due to revolution, the resulting military and political chaos proved to be a massive obstacle for POWs in returning home. In the aftermath of the war, the allies supported the creation of a new country from the vestiges of the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Serbian State, populated mainly by Slavic peoples. This new state came into being in 1918 as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In 1929 it was renamed Yugoslavia, which translates to 'South-Slavs'.

Although the creation of a 'south-slav' homeland had a basis of support from some sections of the 'south-slavs' themselves (and not just an Allied convenience), extreme nationalist forces quickly ensured a troubled existence throughout the inter-war period. It was however very predictable. The Independent Serbian state and the newly freed Croatian populace, having finally escaped 500 and 800 years respectively of domination by Imperialist powers, considered themselves forced into another unwelcome relationship.

WW2 saw a level of brutality and death in Lika unseen since the height of the Ottoman conflicts. It was driven by the fascist NDH state's principle policy of removing Serbs from Croatian territory. The NDH was created in 1941 on the back of the German invasion of Yugoslavia and with the full support of fascist Italy, which had sponsored and groomed its leaders since the mid 1920s. Conditions for the Serb communities in Lika throughout the war are documented elsewhere in Wikipedia et al. The population of the village was decimated. This includes the significant number of men who left the village in 1944, walking out to Italy. They were later resettled by the Allies across Allied countries (mainly USA, UK, Canada, and Australia) after the end of the war, together with the many other displaced persons from Eastern Europe.

At the onset of the conflict in 1941, the village associated itself with the Serbian Royalist forces led by Mihailović based in Ravna Gora and called themselves četniks. Their priority was the protection of the village from the NDH's Ustaše forces. Over time, they became embroiled with the broader regional conflict that involved multiple other fighting forces including Italian and German armies, the Ustaša and the communist Yugoslav Partisans under Josip Broz Tito. Some people from the village later joined the partisans and it was not uncommon for families to be split between četniks and partisans. When the Allies switched logistical and armament support to the partisans in late 1943, the četniks were effectively forced to leave.

Post WW2

At the end of WW2 the partisans re-established the Yugoslav state, securing additional territory. Some villagers who were in the partisans were given land by the authorities in Bačka in the new territory of northeast Yugoslavia, which had been gained from Hungary in the post-war carve up. At the expense of the 'volksdeutsche' (Danube Swabians who at best were expelled and their property confiscated, the Tito government repopulated the area with a major migration from across all Yugoslavia. A few villages in Bačka became 'Lika in the East', the migrants maintaining their Lika traditions.

With many men having left during the war and settled in the West, it left a significant proportion of women in Zalužnica without the prospect of marriage. The remaining families of those men abroad made matches and between 50 and 100 women left the village to join their new husbands following 'proxy' marriages. These marriages were officiated by the Yugoslav state and accepted by Western countries as valid marriage certificates for settlement purposes. The WW2 exodus and subsequent marriages were a second major source of the Zalužnica diaspora.

With Tito breaking from the Soviet Union, the country's economy started to open up in the 1960s. This was bolstered by the German economic explosion from the 1950s and the Yugoslav state's willingness to allow its citizens to work in Germany (also Austria and Switzerland at different times) by way of treaties with those countries. This had a dramatic effect on the village (and generally northern Yugoslavia) from the late 1960s and into the 1970s and 1980s. The most visible outcomes were; construction of new farmhouses across the village, the mechanisation of agriculture (which until the late-1960s was in the main still powered by oxen and horses), and the movement of young people to towns and cities across the country. Some of those working in Germany (and other countries) permanently settled there, forming the third major source of the Zalužnica diaspora.

The 'Croatian Spring' uprising of the late 1960s / early 1970s together with the heightened threat from Croat nationalists in the diaspora, who sought the re-establishment of an independent Croatia, raised tensions throughout the former Krajina. In Zalužnica, a large police presence patrolled the annual Petrovdan celebrations during the early to mid-1970s after widespread rumour of attack. How much of the latter was part of Tito's propaganda machine is open to question.

Tito's death inevitably and predictably led to the dissolution of the Yugoslav state as virulent nationalism took hold. Furthermore, political intrigues within the failing state and the machinations of historic Central European powers combined to force the disintegration of a nation state. The Serbs in the former Krajina established their own 'state', as other communities had done across the crumbling Yugoslavia, informed by the activities of the previous independent Croatian state during WW2. The final act saw the mass migration in 1995 of around one quarter of a million people to Serbia ahead of the known Croatian military offensive. Farmers in Zalužnica released their livestock to the fields and joined the long convoy through the ongoing hostilities in Bosnia to reach the Serbian border. The welcome there was less than warm. Zalužnica people blamed Serbian president Milošević for selling them out following his agreement with Croatian president Tudjman.

The Croatian government's obligations under its pursuit of EU membership resulted in efforts to encourage the former population to return to their homes. War-battered farmhouses of the few elderly who had remained were repaired. A handful of mainly older people returned from Serbia. Others return to their ancestral homes during holiday periods and there are a few new arrivals. Some Croatians have purchased property in the village. A few Roma people have been allowed by local authorities to occupy some farmsteads.

The village farmhouses remain in the most part derelict, particularly away from the main road. The new Zagreb-Split highway that passes close to Otočac has reduced the Plitvice traffic passing through the village as the national park is accessible from the highway. The planned extension from the highway directly to Plitvice and onwards to the south-west will result in the almost total isolation of the village. After nearly 400 years the village and its people were lost to history. However, the increasing popularity of DNA testing, mainly in the diaspora, is slowly starting to rebuild a cultural memory of its people, which for once will remain intact through the internet.

Ancestor Records, Family Trees and DNA

The availability of birth, death and marriage (BDM) records for the village is limited with many destroyed during the multiple conflicts since the village was established. Tracing ancestors beyond living memory is therefore made difficult. What local records do exist are with the Otočac registrars office. This office has access to computerised BDM records from 1910 onwards for the Otočac area, although it is not known how complete these records are. Some older books were moved to the Gospić registrars office the contents of which have not been digitised. Although limited in age, these records do however offer the possibility of finding the names of ancestors born from the early 19th century onwards if they passed after 1910 as well as their parents names on the death record.

The whereabouts of the Zalužnica church records is unknown, although the church survives intact since it was rebuilt in its current form in 1753.

The most readily available resources are in the countries Zalužnica people migrated to. These include records for immigration, BDM, naturalisation etc. Much of this is available online albeit normally at a cost, for example, at www.ancestry.com, although there are free websites such as Ellis Island and www.familyseach.org. Each country will have its own national archives and there are many other niche online information sources such as obituaries and graveyard records.

The main issues in finding ancestors in these 'foreign' records is the misspelling of names and places particularly in the digital records transcribed from the microfiche of the original handwritten documents. While websites offer some level of 'fuzzy' name searches, in many cases it requires patient review of many records of similarly named persons and the associated images (of original records) page by page. Where names and surnames were changed to aid assimilation in the new countries, the ability to trace ancestors through official records is made even more difficult.

Another important resource is Austrian Army records which date from around the mid-18th century to WW1. Some records exist for the various regiments that were located in Krajina and are held at the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb. Some of these records can be viewed at www.familyseach.org, although it is not known if this published collection is all the records from the Archive. You need to register with the website (free of charge). To find these army records choose the 'Catalog' option at the home page. Select the 'author' search term and type 'osterreich armee'. Again, it is not known if this 'search' finds all the Austrian Army records, but there are a substantial number. To find the relevant part of the army records you will need to know a little of the history of the Army. From 1744 to 1872 the Lika-based regiments were known as the 'Grenzer' regiments so for the 'Lika' regiment the relevant set of records scroll down the 'armee' list until you find 'Österreich. Armee. Grenzinfanterie Regiment 01'. The Otočac regiment records are immediately below this under 'Österreich. Armee. Grenzinfanterie Regiment 02'. From 1873, these regiments changed, so the Otocac regiment became known as the IR.79 and some can be found from the main 'armee' search list under 'Österreich. Armee. Infanterie Regiment 079'. Please note that any records in this section for the IR.79 before 1873 are not relevant to Lika.

Within each set of published records there are inconsistencies. There are many instances of 'Lika' and 'Ogulin' regiment records mixed in with 'Otočac' regiment records. Until the start of WW1 the army books were written in German cursive writing, some neater than others. When printed headings started to appear they are still mainly in the German cursive style. Their records have not been transcribed and therefore requires review of every image, of which there are thousands. In a lot of cases the village of origin of a soldier is recorded and to a lesser extent his DoB. In fewer cases, there are a few details of the soldier's children. Further information about the format of these army records and some translations of the form headings will be posted at a later date.

The Austrian Army WW1 casualty lists called 'Verlustliste' are also available online and can be found on a number of free websites, for example, Verlustliste. As the original documents were typed and the Army records fairly accurate, most names are spelt correctly and therefore the 'search' function on the website is fairly accurate. In many cases, it lists the soldier's village (or the closest regiment command post) and date of birth in addition to name, rank, regiment, casualty status and for POWs some list the name of the POW camp. There are only a few entries that list Zalužnica as the village of origin, as Zalužnica soldiers listed the command post at which they enrolled. In order of frequency this is Vrhovine, Škare and Octočac. From 1815 to 1873, Zalužnica was part of the Vrhovine company within the Otočac Grenzer regiment.

The online resource at Croatia Church Records has a subset of 'Orthodox' Lika village church records, but only includes one or two specific years. For whatever reason 1833 and 1856 are the most common. There are no records for Zalužnica, but there are for Škare and Gornja Vrhovine. These may help in discovering any Zalužnica ancestors who married into these or other villages. Again, these records are not transcribed. They are difficult to read as the documents are a mix of printed and handwritten text in an archaic form of Cyrillic and in the language of the day. The 1833 records are unstructured making it even more difficult to transcribe, whereas the those of 1856 and similar years are based on a standardised form. The available records for Gornja Vrhovine have been transcribed by the author and will be posted in the near future.

A useful resource is Radoslav Grujic 'Plemenski rjecnik licko-krbavske zupanije'[15] published in 1915 it lists family surnames and the Lika village in which they were found. Other snippets of information about the village and its population can be found on the internet, but the source is rarely stated making them somewhat inconclusive.

Autosomal DNA tests offer the possibility of finding ancestral relationships, although without knowledge of respective family trees it is very difficult to confirm DNA relationships beyond second cousins. It is further complicated as Lika exhibits the characteristics of an endogamous community. In practice, this means that people often find they are related through both parents (where both parents are from Lika). However, as more people take the test the possibility of finding DNA linkages and relatives will increase substantially.

To preserve the heritage and culture of the Zalužnica and related people, the author encourages publication of family trees, however small, and Autosomal DNA tests to establish ancestral relationships.

Notes and references

- Government of Croatia (October 2013). "Peto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. p. 34. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Bach, Franz (1855). Otocaner Regiments-Geschichte.

- Grbić, Manojlo. Karlovacko Vladicanstvi. 1891.

- Sabljar, Vinko (1866). Miestopisni Riečnik, Dalmacije, Hervatske I Slavonije.

- Političko i sudbeno razdieljenje Kralj. Hrvatske i Slavonije i repertorij prebivališta po stanju od 31. svibnja 1895

- See Ellis Island online database

- "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2011 Census: Zalužnica". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- Uglešić, Antonio. "BEZDANJAČA".

- Fras, Franz de Paula Julius (1835). Cjelovita Topografija Karlovačke Vojne Kranije. p. 179.

- Bach, Franz (1855). Otocaner Regiments-Geschichte.

- Rothenburg, Gunther Erich. The Austrian Military Border In Croatia, 1522-1747. p. 108.

- Grbić, Manojlo. Karlovacko Vladicanstvi. 1891.

- Kaser, Karl (2003). POPIS LIKE I KRBAVE 1712. GODINE. p. 18. ISBN 953-6627-52-3.

- Grujic, Radoslav (1915). Plemenski rjecnik licko-krbavske zupanije. p. 283.

- Try an internet search to locate it.