Yoshinori Shirakawa

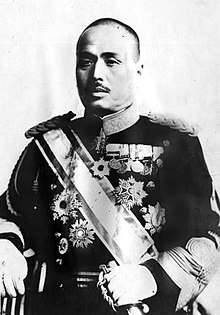

Yoshinori Shirakawa (白川 義則, Shirakawa Yoshinori, January 24, 1869 – May 26, 1932) was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army.

Yoshinori Shirakawa | |

|---|---|

白川 義則 | |

General Yoshinori Shirakawa, c.1921 | |

| 18st Army Minister | |

| In office April 20, 1927 – July 2, 1929 | |

| Monarch | Emperor Hirohito |

| Prime Minister | Tanaka Giichi |

| Preceded by | Kazushige Ugaki |

| Succeeded by | Kazushige Ugaki |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 24, 1868 Iyo, Japan |

| Died | May 26, 1932 (aged 64) Shanghai, China |

| Awards |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Empire of Japan |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1890–1932 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

Biography

Early life and education

Shirakawa was born as the third son of an ex-samurai of Matsuyama Domain in Iyo, Ehime, Shikoku. He attended Matsuyama Middle School, but was forced to leave without graduating due to the difficult financial situation of his family, and worked as a substitute teacher. In January 1886, he secured a position with a military cadet school and was enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Army as a sergeant in military engineering attached to the Guards Infantry Regiment. In December 1887 he was recommended as an officer cadet and served with the IJA 21st Infantry Regiment. He graduated from the 1st class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1890, where his classmates included Kazushige Ugaki. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in March 1891.

Military career

Shirakawa entered the Army Staff College in 1893, but was forced to leave the following year due to the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War. During the war, he was promoted to first lieutenant. He returned to graduate from the Army Staff College and was promoted to captain in 1898. Shirakawa was then assigned as section commander of the IJA 21st Infantry Regiment. In 1902, he was assigned to the staff of the Guards Division.

Promoted to major in 1903, Shirakawa returned to command the IJA 21st Infantry Regiment during the Russo-Japanese War. During the war, he was transferred to the staff of the IJA 13th Division. This division was given the independent assignment of occupying Sakhalin before the conclusion of the Portsmouth Treaty,[1] landing on Sakhalin on 7 July 1905, only three months after being formed, and securing the island by 1 August 1905. As a result of its successful operation, Japan was awarded southern Karafuto during the Portsmouth Treaty, one of Japan's few territorial gains during the war. After the war, Shirakawa was assigned to the Personnel Bureau of the Army Ministry from October 1905. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1907, colonel in 1909, and commander of the IJA 34th Infantry Regiment.[2]

In June 1911, Shirakawa became Chief of Staff of the IJA 11th Division, and was promoted to major general and commander of the IJA 9th Infantry Brigade.He served as Head of the Personnel Bureau from 1916 to 1919, and after his promotion to lieutenant general and commandant of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy.

In March 1921, he was given a combat command again, as commander of the IJA 11th Division, overseeing its withdrawal and return to Japan aferthe Japanese intervention in Siberia. In August 1922, he was transferred to command the IJA 1st Division. He was selected by General Yamanashi Hanzō to serve as Vice-Minister of the Army in October 1922 and also served as Head of Army Aeronautical Department.[3] during which time he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun. Shirakawa was appointed commander of the Kwangtung Army from October 1923.

Army Minister and death

Promoted to full general in March 1925, Shirakawa subsequently served on the Supreme War Council from 1926 to 1932, and was Army Minister from 1927 to 1929 in the cabinet of Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi.

During his tenure as Army Minister, the Kwangtung Army staged the Huanggutun incident as assassinate Fengtian warlord Zhang Zuolin in June 1928. Prime Minister Tanaka reported to Emperor Hirohito that the incident had been staged by rogue junior officers within the Imperial Japanese Army without orders from Tokyo and demanded that the perpetrators be punished. While Shirakawa's role in the bombing remains uncertain, he refused to punish the perpetrators and instead transferred them to other posts to avoid a court martial.

With tensions in China rapidly ramping up towards open war, with the Shanghai Incident starting in January 1932, Shirakawa was dispatched to China on February 25, 1932, to become commander of the Shanghai Expeditionary Army. he was under direct orders from Emperor Hirohito to bring the situation to a close. Shirakawa issued a cease-fire order on March 3 over the strong objections of his commanders and greatly angering The Imperial Japanese Army General Staff. However, the emperor was pleased, and the League of Nations General Assembly, which was poised to issue a strong condemnation of Japan, remained silent. However, two months later, on April 29, 1932, he was severely injured by a bomb set by Korean independence activist Yoon Bong-gil in Shanghai's Hongkou Park and died of his injuries on May 26.[4]

Legacy

Shirakawa was posthumously awarded with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers, Order of the Golden Kite 2nd Class, and elevated to the rank of danshaku (baron) under the kazoku peerage system.[5] His ashes were divided between graves located in his hometown of Matsuyama and in Tokyo's Aoyama Cemetery.

Decorations

- 1895 –

_6Class_BAR.svg.png)

- 1902 –

_5Class_BAR.svg.png)

- 1906 –

- 1906 –

- 1914 –

_3Class_BAR.svg.png)

- 1920 –

_2Class_BAR.svg.png)

- 1920 –

- 1922 –

- 1932 –

- 1932 –

References

- Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1992). Encyclopedia of Military Biography. I B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 1-85043-569-3.

- Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868–2000. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

External links

- Ammenthorp, Steen. "Shirakawa Yoshinori". The Generals of World War II.

- Wendel, Marcus. "List of Commanders of the Kwantung Army". Axis History Factbook.

Notes

- Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 107.

- Ammenthorp, The Generals of World War II

- Wendel, Axis History Factbook

- Dupuy, Encyclopedia of Military Biography

- 『官報』第1617号「叙任及辞令」1932年5月24日。

- 『官報』第5824号「叙任及辞令」1902年12月1日。

- 『官報』号外「叙任及辞令」1906年12月11日。

- 『官報』号外「叙任及辞令」1906年12月11日。

- 『官報』第2246号「叙任及辞令」1920年1月31日。

- 『官報』第2612号「叙任及辞令」1921年4月19日。

- 『官報』第3347号「授爵・叙任及辞令」1923年10月18日。

- 『官報』第1620号「叙任及辞令」1932年5月27日。

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Kazushige Ugaki |

Minister of War April 1927 – July 1929 |

Succeeded by Kazushige Ugaki |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by none |

Commander, Shanghai Expeditionary Army February 1932 – April 1932 |

Succeeded by Nobuyoshi Mutō |

| Preceded by Shinobu Ono |

Commander, Kwantung Army October 1923 – July 1926 |

Succeeded by Nobuyoshi Mutō |