Kelvin

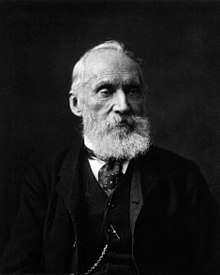

The kelvin is the base unit of temperature in the International System of Units (SI), having the unit symbol K. It is named after the Belfast-born, Glasgow University engineer and physicist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin (1824–1907).

| Kelvin | |

|---|---|

| Unit system | SI base unit |

| Unit of | Temperature |

| Symbol | K |

| Named after | William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin |

The kelvin is now defined by fixing the numerical value of the Boltzmann constant k to 1.380 649×10−23 J⋅K−1. This unit is equal to kg⋅m2⋅s−2⋅K−1, where the kilogram, metre and second are defined in terms of the Planck constant, the speed of light, and the duration of the caesium-133 ground-state hyperfine transition respectively.[1] Thus, this definition depends only on universal constants, and not on any physical artifacts as practiced previously, such as the International Prototype of the Kilogram, whose mass diverged over time from the original value.

One kelvin is equal to a change in the thermodynamic temperature T that results in a change of thermal energy kT by 1.380 649×10−23 J.[2]

The Kelvin scale fulfills Thomson's requirements as an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale. It uses absolute zero as its null point.

Unlike the degree Fahrenheit and degree Celsius, the kelvin is not referred to or written as a degree. The kelvin is the primary unit of temperature measurement in the physical sciences, but is often used in conjunction with the degree Celsius, which has the same magnitude.

History

In 1848, William Thomson, who was later identified as Lord Kelvin, wrote in his paper, On an Absolute Thermometric Scale, of the need for a scale whereby "infinite cold" (absolute zero) was the scale's null point, and which used the degree Celsius for its unit increment. Kelvin calculated that absolute zero was equivalent to −273 °C on the air thermometers of the time.[3] This absolute scale is known today as the Kelvin thermodynamic temperature scale. Kelvin's value of "−273" was the negative reciprocal of 0.00366—the accepted expansion coefficient of gas per degree Celsius relative to the ice point, giving a remarkable consistency to the currently accepted value.

In 1954, Resolution 3 of the 10th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) gave the Kelvin scale its modern definition by designating the triple point of water as its second defining point and assigned its temperature to exactly 273.16 kelvin.[4]

In 1967/1968, Resolution 3 of the 13th CGPM renamed the unit increment of thermodynamic temperature "kelvin", symbol K, replacing "degree Kelvin", symbol °K.[5] Furthermore, feeling it useful to more explicitly define the magnitude of the unit increment, the 13th CGPM also held in Resolution 4 that "The kelvin, unit of thermodynamic temperature, is equal to the fraction 1/273.16 of the thermodynamic temperature of the triple point of water."[6]

In 2005, the Comité International des Poids et Mesures (CIPM), a committee of the CGPM, affirmed that for the purposes of delineating the temperature of the triple point of water, the definition of the Kelvin thermodynamic temperature scale would refer to water having an isotopic composition specified as Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water.[7]

On 16 November 2018, a new definition was adopted, in terms of a fixed value of the Boltzmann constant. With this change the triple point of water became an empirically determined value of approximately 273.16 kelvin

. For legal metrology purposes, the new definition officially came into force on 20 May 2019, the 144th anniversary of the Metre Convention.[8]

Usage conventions

According to the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, when spelled out or spoken, the unit is pluralised using the same grammatical rules as for other SI units such as the volt or ohm (e.g. "the triple point of water is not exactly 273.16 kelvin"[9]). When reference is made to the "Kelvin scale", the word "kelvin"—which is normally a noun—functions adjectivally to modify the noun "scale" and is capitalized. As with most other SI unit symbols (angle symbols, e.g. 45° 3′ 4″, are the exception) there is a space between the numeric value and the kelvin symbol (e.g. "99.987 K").[10][11] (The style guide for CERN, however, specifically says to always use "kelvin", even when plural.)[12]

Before the 13th CGPM in 1967–1968, the unit kelvin was called a "degree", the same as with the other temperature scales at the time. It was distinguished from the other scales with either the adjective suffix "Kelvin" ("degree Kelvin") or with "absolute" ("degree absolute") and its symbol was °K. The latter term (degree absolute), which was the unit's official name from 1948 until 1954, was ambiguous since it could also be interpreted as referring to the Rankine scale. Before the 13th CGPM, the plural form was "degrees absolute". The 13th CGPM changed the unit name to simply "kelvin" (symbol: K).[13] The omission of "degree" indicates that it is not relative to an arbitrary reference point like the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales (although the Rankine scale continued to use "degree Rankine"), but rather an absolute unit of measure which can be manipulated algebraically (e.g. multiplied by two to indicate twice the amount of "mean energy" available among elementary degrees of freedom of the system).

2019 redefinition

In 2005 the CIPM embarked on a programme to redefine the kelvin (along with the other SI units) using a more experimentally rigorous methodology. In particular, the committee proposed redefining the kelvin such that Boltzmann constant takes the exact value 1.3806505×10−23 J/K.[14] The committee had hoped that the programme would be completed in time for its adoption by the CGPM at its 2011 meeting, but at the 2011 meeting the decision was postponed to the 2014 meeting when it would be considered as part of a larger programme.[15]

The redefinition was further postponed in 2014, pending more accurate measurements of Boltzmann's constant in terms of the current definition,[16] but was finally adopted at the 26th CGPM in late 2018, with a value of k = 1.380649×10−23 J/K.[14][17]

From a scientific point of view, the main advantage is that this will allow measurements at very low and very high temperatures to be made more accurately, as the techniques used depend on the Boltzmann constant. It also has the philosophical advantage of being independent of any particular substance. The challenge was to avoid degrading the accuracy of measurements close to the triple point. From a practical point of view, the redefinition will pass unnoticed; water will still freeze at 273.15 K (0 °C),[18] and the triple point of water will continue to be a commonly used laboratory reference temperature.

The difference is that, before the redefinition, the triple point of water was exact and the Boltzmann constant had a measured value of 1.38064903(51)×10−23 J/K, with a relative standard uncertainty of 3.7×10−7.[17] Afterward, the Boltzmann constant is exact and the uncertainty is transferred to the triple point of water, which is now 273.1600(1) K.

Practical uses

| from kelvins | to kelvins | |

|---|---|---|

| Celsius | [°C] = [K] − 273.15 | [K] = [°C] + 273.15 |

| Fahrenheit | [°F] = [K] × 9⁄5 − 459.67 | [K] = ([°F] + 459.67) × 5⁄9 |

| Rankine | [°R] = [K] × 9⁄5 | [K] = [°R] × 5⁄9 |

| For temperature intervals rather than specific temperatures, 1 K = 1 °C = 9⁄5 °F = 9⁄5 °R Comparisons among various temperature scales | ||

Colour temperature

The kelvin is often used as a measure of the colour temperature of light sources. Colour temperature is based upon the principle that a black body radiator emits light with a frequency distribution characteristic of its temperature. Black bodies at temperatures below about 4000 K appear reddish, whereas those above about 7500 K appear bluish. Colour temperature is important in the fields of image projection and photography, where a colour temperature of approximately 5600 K is required to match "daylight" film emulsions. In astronomy, the stellar classification of stars and their place on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram are based, in part, upon their surface temperature, known as effective temperature. The photosphere of the Sun, for instance, has an effective temperature of 5778 K.

Digital cameras and photographic software often use colour temperature in K in edit and setup menus. The simple guide is that higher colour temperature produces an image with enhanced white and blue hues. The reduction in colour temperature produces an image more dominated by reddish, "warmer" colours.

Kelvin as a unit of noise temperature

In electronics, the kelvin is used as an indicator of how noisy a circuit is in relation to an ultimate noise floor, i.e. the noise temperature. The so-called Johnson–Nyquist noise of discrete resistors and capacitors is a type of thermal noise derived from the Boltzmann constant and can be used to determine the noise temperature of a circuit using the Friis formulas for noise.

Unicode character

The symbol is encoded in Unicode at code point U+212A K KELVIN SIGN. However, this is a compatibility character provided for compatibility with legacy encodings. The Unicode standard recommends using U+004B K LATIN CAPITAL LETTER K instead; that is, a normal capital K. "Three letterlike symbols have been given canonical equivalence to regular letters: U+2126 Ω OHM SIGN, U+212A K KELVIN SIGN, and U+212B Å ANGSTROM SIGN. In all three instances, the regular letter should be used."[19]

See also

- Comparison of temperature scales

- International Temperature Scale of 1990

- Negative temperature

References

- "BIPM - SI Brochure". www.bipm.org. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Mise en pratique" (PDF). BIPM.

- Lord Kelvin, William (October 1848). "On an Absolute Thermometric Scale". Philosophical Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Resolution 3: Definition of the thermodynamic temperature scale". Resolutions of the 10th CGPM. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1954. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Resolution 3: SI unit of thermodynamic temperature (kelvin)". Resolutions of the 13th CGPM. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1967. Archived from the original on 21 April 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Resolution 4: Definition of the SI unit of thermodynamic temperature (kelvin)". Resolutions of the 13th CGPM. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1967. Archived from the original on 15 June 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Unit of thermodynamic temperature (kelvin)". SI Brochure, 8th edition. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1967. pp. Section 2.1.1.5. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Draft Resolution A "On the revision of the International System of units (SI)" to be submitted to the CGPM at its 26th meeting (2018) (PDF)

- "Rules and style conventions for expressing values of quantities". SI Brochure, 8th edition. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1967. pp. Section 2.1.1.5. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "SI Unit rules and style conventions". National Institute of Standards and Technology. September 2004. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Rules and style conventions for expressing values of quantities". SI Brochure, 8th edition. Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 1967. pp. Section 5.3.3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- "kelvin | CERN writing guidelines". writing-guidelines.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Barry N. Taylor (2008). "Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)" (.PDF). Special Publication 811. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ian Mills (29 September 2010). "Draft Chapter 2 for SI Brochure, following redefinitions of the base units" (PDF). CCU. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "General Conference on Weights and Measures approves possible changes to the International System of Units, including redefinition of the kilogram" (PDF) (Press release). Sèvres, France: General Conference on Weights and Measures. 23 October 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Wood, B. (3–4 November 2014). "Report on the Meeting of the CODATA Task Group on Fundamental Constants" (PDF). BIPM. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2015.

[BIPM director Martin] Milton responded to a question about what would happen if ... the CIPM or the CGPM voted not to move forward with the redefinition of the SI. He responded that he felt that by that time the decision to move forward should be seen as a foregone conclusion.

- Newell, D B; Cabiati, F; Fischer, J; Fujii, K; Karshenboim, S G; Margolis, H S; de Mirandés, E; Mohr, P J; Nez, F; Pachucki, K; Quinn, T J; Taylor, B N; Wang, M; Wood, B M; Zhang, Z; et al. (Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA) Task Group on Fundamental Constants) (29 January 2018). "The CODATA 2017 values of h, e, k, and NA for the revision of the SI". Metrologia. 55 (1): L13–L16. Bibcode:2018Metro..55L..13N. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/aa950a.

- "Updating the definition of the kelvin" (PDF). International Bureau for Weights and Measures (BIPM). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- "22.2". The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA, USA: The Unicode Consortium. August 2015. ISBN 978-1-936213-10-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

External links

| Look up kelvin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2006). "The International System of Units (SI) Brochure" (PDF). 8th Edition. International Committee for Weights and Measures. Retrieved 6 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)