Ye Qianyu

Ye Qianyu (or Yeh Ch'ien-yü; 31 March 1907 – 5 May 1995) was a Chinese painter and pioneering manhua artist. In 1928, he cofounded Shanghai Manhua, one of the earliest and most influential manhua magazines, and created Mr. Wang, one of China's most famous comic strips.

Ye Qianyu 叶浅予 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ye Qianyu and wife Wang Renmei | |||||||||

| Born | Ye Lunqi (葉綸綺) 31 March 1907 | ||||||||

| Died | 5 May 1995 (aged 88) | ||||||||

| Known for | Manhua and Chinese painting | ||||||||

Notable work | Shanghai Manhua Mr. Wang Liberation of Beiping | ||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Luo Caiyun (1930s) Dai Ailian (1940–51) Wang Renmei (1955–87) | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 葉淺予 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 叶浅予 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Ye was also a master of traditional Chinese painting and served as the head of the Department of Chinese Painting of the China Central Academy of Fine Arts. During the Cultural Revolution he was persecuted and imprisoned for seven years.

Ye was married three times. His first two marriages, to Luo Caiyun and dancer Dai Ailian, ended in divorce. His third marriage, to movie star Wang Renmei, lasted more than 30 years until Wang's death.

Early life

Ye Qianyu was born Ye Lunqi (葉綸綺) in Tonglu county, Zhejiang province in 1907. Although he loved to paint since childhood, he had neither the money nor the opportunity to seek professional training, forcing him to teach himself how to paint.[1]

Career in Shanghai

.jpg)

At age 18 Ye moved to Shanghai,[2] where he found work at a small, short-lived journal Sanri Huabao (Three Day Pictorial). The journal shut down when Chiang Kai-shek's Northern Expedition army reached Shanghai in April 1927.[3]

Out of work, Ye Qianyu, then 20 years old, together with fellow cartoonists Huang Wennong and Lu Shaofei released a publication dedicated to manhua, called Shanghai Manhua (or Shanghai Sketch). The first effort looked like a propaganda poster and was a failure. Undeterred, the original three, joined by eight more artists including Zhang Guangyu, Ding Song, and Wang Dunqing, formed the Shanghai Sketch Society (also translated as Shanghai Cartoon Association) in the autumn of 1927.[3] It was China's first association dedicated to manhua, and its debut was a major event in the history of Chinese comics.[4]:30

Under the leadership of Zhang Guangyu, who recruited the wealthy poet Shao Xunmei as a sponsor,[3] the association successfully relaunched the Shanghai Manhua on 21 April 1928.[5] Ye drew several covers for the magazine[3] and the back page of the publication carried his comic strip, Mr. Wang. Inspired by the American strip Bringing Up Father and portraying the daily life of the middle and lower classes of Shanghai,[6] Mr. Wang became one of China's most famous cartoons, eventually being made into 11 films in the 1930s and 40s.[7]:86

In June 1930 Shanghai Manhua was merged into Modern Miscelleny (or Modern Pictorial, 时代画报),[5] of which Ye became an editor while continuing his Mr. Wang series.[6]

In September 1936, Ye Qianyu, Lu Shaofei, and Zhang Guangyu organized the First National Cartoon Exhibition in Shanghai. It displayed over 600 cartoons from all over the country. After the overwhelming success of the exhibition, the artists formed the National Association of Chinese Cartoonists in the spring of 1937. The blossoming movement, however, was brought to a halt by the Japanese invasion a few months later.[4]:34

Second Sino-Japanese War

When Japan invaded China and occupied Shanghai in 1937, Ye Qianyu, together with a group of fellow Shanghai cartoonists, formed the "National Salvation Cartoon Propaganda Corps", which included well-known artists Zhang Leping, Lu Zhixiang, Te Wei, and Hu Kao.[7]:79 Ye's lover, Liang Baibo, was the only female member.[8] Funded by the Kuomintang government, the corps left Shanghai for the interior to spread anti-Japanese propaganda.[7]:79 They first went to Wuhan, but were forced to leave when that city fell at the end of 1938. They then travelled to Changsha, Guilin, and eventually to the wartime capital Chongqing. They published 15 issues of Resistance Cartoons before the government discontinued funding.[7]:91

Ye went to Hong Kong prior to its fall to the Japanese in December 1941, and traveled through Guizhou, Guangxi, and Vietnam. In 1943 he temporarily worked for the US General Joseph Stilwell as a war correspondent in India. Throughout his travels he drew many sketches of wartime scenes, including a series entitled Escape from Hong Kong.[7]:92

After World War II

After the surrender of Japan in 1945, Ye Qianyu went to the United States, where he held a series of exhibitions to show and sell his artworks.[1]

In 1947, Ye became a professor at the Beiping (Beijing) Art Academy. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, he remained at the academy, which was transformed into the China Central Academy of Fine Arts.[1] He was also elected vice-chairman of the China Artists Association.[9] In 1954, he was appointed head of the Chinese Painting Department of the academy. He painted prolifically in the 1950s, including such representative works as Indian Dancing, Autumn of the Summer River, and The Liberation of Beiping.[1]

When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, Ye Qianyu was accused of being a Kuomintang (KMT) agent for having drawn propaganda paintings and cartoons for the KMT government during the Japanese invasion. The Red Guards labeled him as a KMT "Major General" because he was better paid than a real general. He was imprisoned for seven years.[10] After his release in 1975, he was allowed to return to work at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, as a janitor.[10] He nearly died of a heart attack the following year, and underwent a major operation in 1978. His wife Wang Renmei supported the family during this period.[10]

Ye Qianyu was politically rehabilitated in 1979. In 1981 he was appointed Vice President of the Research Institute of Chinese painting, and re-elected vice-chairman of the China Artists Association and member of the National Committee of the CPPCC. He died in 1995 in Beijing, aged 88.[1]

Personal life

Ye Qianyu was married three times. At age 23, he married Luo Caiyun (罗彩云), who was from a prominent family in his hometown Tonglu. The marriage was arranged by their parents. She gave birth to a son Ye Shen (叶申) and a daughter Ye Mingming (叶明明).[11][12]

In 1935, while he was an editor with the Modern Sketch magazine, Ye fell in love with Liang Baibo, one of the first female Chinese cartoonists and creator of the comic strip Miss Bee. Luo Caiyun rejected Ye's request for divorce, but they agreed to become legally separated.[8][12]

At the start of the Sino-Japanese War, Liang Baibo joined Ye's Salvation Cartoon Propaganda Corps and went to Wuhan with him. However, Liang met and fell in love with an air force pilot in Wuhan, eventually following him to Taiwan.[8][12] She suffered from mental illness in her later years and committed suicide circa 1970.[8][11]

In 1940 Ye Qianyu met the dancer Dai Ailian in Hong Kong. An overseas Chinese born in Trinidad, Dai had come to Hong Kong to support the war effort. Although Dai could not speak Chinese and Ye spoke little English, they fell in love and got married within a few weeks. Soong Ching-ling, the widow of President Sun Yat-sen, presided over their wedding.[11] Because of a botched surgery in Hong Kong, Dai was unable to have children. According to Ye Qianyu's daughter Mingming, who lived with her father and was initially hostile to her stepmother, Dai treated her as if she had been her own child.[11]

In 1950 Ye spent more than half a year in Xinjiang. When he returned to Beijing, Dai Ailian unexpectedly asked for divorce, because she had fallen in love with her dance partner. Ye was devastated; the divorce was finalized in 1951. Dai Ailian lived until 2006, and is now known as the "Mother of Chinese ballet".[11]

Ye's last wife was Wang Renmei, a famous actress who had been previously married to the "Film Emperor" Jin Yan. Introduced by mutual friends, they got married in 1955. The marriage was stormy from the beginning, but it lasted more than 30 years, through the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, until Wang's death in 1987.[11]

Luo Caiyun, Ye Qianyu's first wife, lived with their son Ye Shen in Wuxi, Jiangsu.[12] When Ye Qianyu was accused of being a KMT agent and thrown into prison during the Cultural Revolution, Luo was persecuted for being his ex-wife.[11] She committed suicide in 1970.[12]

Selected works

.jpg) Woman and the Serpent, cover for Shanghai Manhua, 12 May 1928

Woman and the Serpent, cover for Shanghai Manhua, 12 May 1928.jpg) Summer Fashions from Shanghai Manhua, 26 May 1928

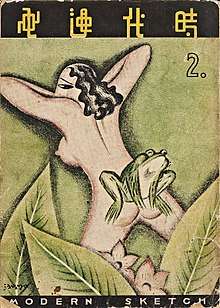

Summer Fashions from Shanghai Manhua, 26 May 1928 Cover of Modern Sketch issue 2, 1934

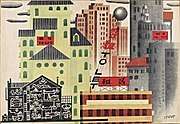

Cover of Modern Sketch issue 2, 1934 Supply Exceeds Demand and Demand Exceeds Supply, Nov. 1935

Supply Exceeds Demand and Demand Exceeds Supply, Nov. 1935

References

- Song, Yuwu (2013). Biographical Dictionary of the People's Republic of China. McFarland. p. 712. ISBN 9781476602981.

- Zou, Yong (2007-06-19). 有十个叶浅予,中国就文艺复兴了 (in Chinese). China Radio International. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- Laing, Ellen Johnston (October 2010). "Shanghai Manhua, the Neo-Sensationist School of Literature, and Scenes of Urban Life". Ohio State University. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- Hung, Chang-tai (1994). War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082366.

- 《上海漫画》 [Shanghai Manhua] (in Chinese). Phoenix TV. 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Lent, John A., ed. (2001). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. University of Hawaii Press. p. 114. ISBN 9780824824716.

- FitzGerald, Carolyn (2013). Fragmenting Modernisms: Chinese Wartime Literature, Art, and Film, 1937-49. Chapter 2: BRILL. ISBN 9789004250994.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Lent, John A.; Ying, Xu (2017). Comics Art in China. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-1-4968-1177-6.

- "中国美协简介" (in Chinese). China Artists Association. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- Meyer, Richard J. (2013). Wang Renmei: The Wildcat of Shanghai. Hong Kong University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9789888139965.

- Ye, Mingming (2013-04-20). 父亲叶浅予和我的三个妈妈 [My father Ye Qianyu and my three mothers]. Wen Hui Bao (in Chinese). Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Zhao, Zhen (赵朕); Wang, Yixin (王一心) (2009-02-01). "57. 覆水难收的婚姻悲剧:叶浅予与罗彩云和梁白波" [A tragic marriage: Ye Qianyu, Luo Caiyun, and Liang Baibo]. 文化人的人情脉络 (in Chinese). Beijing: Tuanjie Publishing House. ISBN 9787802145078. Retrieved 2014-01-07.