Xépôn

Xépôn (also known as Tchepone and Sepon), is a village in the Seponh District of Savannakhet Province, Laos. It was approximately 0.65 kilometres (0.40 mi) east of the intersection of the Sepon River and the Banghiang River. It was the target of Operation Lam Son 719 in 1971, an attempt by the armed forces of South Vietnam and the United States to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The village now known as Old Xépôn (Xépôn Kao in Lao) was destroyed. In the 1990s, gold mining began at the site, helping to create Lao's largest private industry. Expansion of mining in the area has dislocated indigenous villages around Old Xépôn.[1]

Geography

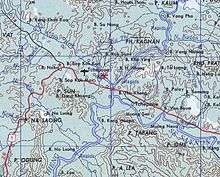

Xépôn was on the north bank of the Sepon River at an elevation of 170 metres (560 ft).[2] The countryside is mountainous, broken, and covered in subtropical forest. Average rainfall each year is 189 centimetres (74 in). In the rainy season (July to September), rainfall could be 41 to 51 centimetres (16 to 20 in) a month.[3]

The Sepon River runs in a trough between two natural, high ridges. The trough itself is only 3.5 to 5 kilometres (2.2 to 3.1 mi) wide. This geologic feature begins just west of the town of Khe Sanh in Vietnam. The northern ridge ends near Xépôn, while the southern ridge continues for another 80 kilometres (50 mi). A shallow bowl forms between the ridges (permitting north-south traffic out of the valley) near the Laotian town of Ban Dong. The southern ridge turns southwest (followed by Route 9 on the north side and the Banghiang River on the south side), and ends near the town of Mường Phìn. However, the best break in these ridges occurred at Xépôn, where land traffic could move east, southeast, and southwest.[4]

History

Human occupation of Xépôn goes back at least 2,000 years. There is evidence of a large copper mining complex, with some shafts up to 66 feet (20 m) deep, in the area around the village.[5] Human burial sites from the same period are also located near these ancient copper mines, making them (as archeologist Charles Higham concludes) one of the most important burial sites in all of Southeast Asia.[5]

Xépôn was most likely settled in the 1500s by settlers from the Muong Thanh Valley in Vietnam.[6]

During the period when France ruled Laos as a colony, the French constructed Route 9. Opened about 1930,[7] Route 9 ran from the major city of Savannakhet on the Thai-Laotian border in the west across the entire country to the border with Vietnam in the east.[8] It met National Route 9, a major Vietnamese highway, at the border.[9] Just a few meters upriver from where the Sepon and Banghiang rivers met, Route 9 crossed the Banghiang. The bridge here had three spans, and could accommodate much traffic.[10]

Xépôn also played a role in anti-colonial movements in Laos. In the aftermath of World War II, a Laotian independence movement, the Lao Issara, formed to seek national independence. Thao Ō Anourack, a native of Xépôn, was appointed commander of all Lao Issara forces in the district.[11] Initially successful, French forces seized the capital of Vientiane by April 1946. Most of the Lao Issara fled to Thailand. In September 1946, however, several Laotian leaders met in the Vietnamese city of Vinh and, with the sponsorship of the Viet Minh movement, formed the Committee for Lao Resistance in the East to carry on the fight for independence. Thao Ō Anurak was one of the founding members of the committee.[12]

Due to its location near the ridge breaks and two major rivers, the village of Xépôn is estimated to have had about 1,500 inhabitants in 1960. Just five years later, half of the residents had fled due to war.[9]

Air base

During the 1950s, the French military built a military airfield near Xépôn. The airfield was located about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) northwest of the village on the south bank of the Nam Se Kok River. At 1,128 metres (3,701 ft) in length, the dirt airstrip was the largest in Savannakhet Province, and the second largest airfield of any in the nearby South Vietnamese provinces. The Royal Lao Army ceased defending the airfield in 1961, and it fell into North Vietnamese hands.[2]

Xépôn proved to be a critical point on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The trail was a series of supply routes along through Laos which North Vietnam used to supply forces of both the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Viet Cong guerrilla forces, both of which were operating in South Vietnam. Route 9 provided a quick way to move supplies east. The light Vietnamese trucks could also cross the Banghiang River at Xépôn which, although 30 metres (98 ft) across was just 1 metre (3.3 ft) deep most of the year, and then travel further south.[4] This made Xépôn the choke point for almost all motorized traffic passing through Mu Gia Pass, the main Ho Chi Minh Trail entry point into Laos.[13] Only Route 23, which led south from Mường Phìn, provided a good alternative.[14] The North Vietnamese invested Xépôn in December 1958,[15] and built a large, heavily defended military base there to defend the area.[2]

Operation Lam Son 719

U.S. officials believed that Xépôn was abandoned by 1970.[16]

In 1971, Xépôn was the focus of Operation Lam Son 719.[8] On 8 February, I Corps of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)—supported by long-range artillery, bombers, and helicopters provided by the U.S. armed forces—invaded Laos. The objective was Xépôn, where the air base was to be made operational. The goal was to interdict the Ho Chi Minh Trail for three months. The operation was a complete failure. Instead of attacking at the end of the rainy season (when North Vietnamese troops would be very under supplied), the attack began three months later, long after their supplies had been replenished. I Corps officers, many of whom were suspected of North Vietnamese sympathies, were told of the operation at the last minute. Press reports of the operation leaked almost as soon as the attack began, alerting North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces. Logistical planning by the South Vietnamese and the U.S. was poor. Nearly 8,000 ARVN troops were lost, and more than 100 U.S. helicopters. Nearly US$1 million in military equipment was abandoned as ARVN forces fled Laos in a near-rout on 24 March.[14]

It is not clear whether Xépôn was still occupied by the North Vietnamese troops at the time. U.S. officials reported large quantities of food, ammunition, and other supplies cached in and around Xépôn, and that ARVN troops and U.S. aircraft destroyed them.[17] But other reports indicate that, while supply caches were destroyed, Xépôn had already been abandoned by the North Vietnamese in favor of other routes.[18]

Operation Lam Son 719 destroyed Xépôn and left it deserted.[19]

Modern Xépôn

During the Laotian Civil War, the Pathet Lao captured Xépôn in early May 1975.[20] The Pathet Lao toppled the constitutional monarchy of Laos on December 2, 1975. In the years after the new government took power, a new town using the name Xépôn was built on the site of the old French airfield. By 1998, the new town had a population of about 35,600.[21]

The site of Old Xépôn (Xépôn Kao in Laotian) has few remains. A new temple was constructed on the site of the town wat, and a safe and pile of bricks marks the town's former bank.[22]

Gold was discovered near Xépôn by Conzinc Riotinto of Australia/Rio Tinto Group in 1993. More gold deposits were identified by Oxiana in 2000. Known gold deposits total 110,000 kilograms (240,000 lb) of gold. Industrial gold mining began in late December 2002.[23]

Extensive copper deposits were discovered 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Xépôn in 2000. Construction of a large copper mine, the most technologically advanced in Asia, began in 2003. Copper production began in 2005.[24] These mines produced 67,561 metric tons (10,639,000 st) of copper, 3,267 kilograms (7,203 lb) of gold, and 1,031 kilograms (2,273 lb) of silver in 2009. The same year, the company Lane Xang Minerals Limited began a US$60.4 million expansion of the copper mine designed to raise yearly production to 85,000 metric tons (13,400,000 st).[25] As of 2010, the copper and gold mine at Xépôn was Laos' largest private business, and its largest private employer.[26]

Fourteen villages directly within the core mine zone had been relocated. About seventy more villages are within the mine concession but these had not yet been asked to move. Communities impacted by the Sepon mine include Makong, Tri (Try), Kri and Lao Loum, the dominant ethnic Lao. Although many of the communities have not been asked to relocate, water pollution and deforestation forced many to leave their villages. Some resettled at the mine resettlement site.[1]

References

- Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact. Indigenous Women in Southeast Asia: Challenges in Their Access to Justice. Chiang Mai, Thailand: March 2013. Accessed 2013-12-16.

- Collins, p. 373.

- Collins, p. 375.

- Collins, p. 371.

- Higham, p. 184.

- Cheesman, p. 152.

- Stuart-Fox, p. 49.

- Nguyen and Dommen, p. 252.

- Collins, p. 372.

- Collins, p. 335.

- Savada, p. 29.

- Stuart-Fox, p. 71.

- Perlstein, p. 546.

- Collins, p. 378.

- Phraxayavong, p. 76.

- Van Atta, p. 347.

- Van Atta, p. 346-347.

- "Crossroads at Tchepone." Life. March 26, 1971, p. 31. Accessed 2013-03-25; "LAM SON 719, Operation," in Vietnam War: The Essential Reference Guide, p. 131.

- Miller, p. 146.

- Savada, p. 54.

- Cummings, p. 262.

- Burke, Vaisutis, and Cummings, p. 250.

- Manini, Tony and Albert, Peter. Exploration and Development of the Sepon Gold and Copper Deposits, Laos. Oxiana Limited. 2006. Accessed 2013-01-10.

- Thomaz, Carla. "Sepon Mine, Laos." The Australian. November 30, 2007. Accessed 2013-01-10.

- Fong-Sam, p. 16.1.

- Chandrasekaran, p. 256.

Sources

- Burke, Andrew; Vaisutis, Justine; and Cummings, Joe. Laos. London: Lonely Planet, 2007.

- Chandrasekaran, V.C. Rubber as a Construction Material for Corrosion Protection: A Comprehensive Guide for Process Equipment Designers. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Cheesman, Patricia. "The Spirit Skirts of the Lao-Tai Peoples in Laos." In The Secrets of Southeast Asian Textiles: Myth, Status, and the Supernatural. Jane Puranananda, ed. Bangkok: James H. W. Thompson Foundation, 2007.

- Collins, John M. Military Geography for Professionals and the Public. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1998.

- Cummings, Joe. Laos. London: Lonely Planet, 1998.

- Fong-Sam, Yolanda. "The Mineral Industry of Laos." In Minerals Yearbook. Volume III, Area Reports, International 2009, Asia and the Pacific. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 2011.

- Higham, Charles. "Southeast Asia." In The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Neil Asher Silberman, Alexander A. Bauer, et al., eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- "LAM SON 719, Operation." In Vietnam War: The Essential Reference Guide. James H. Willbanks, ed. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2013.

- Miller, John Grider. The Co-Vans: US Marine Advisors in Vietnam. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2000.

- Nguyen, Phu Duc and Dommen, Arthur J. The Viet-Nam Peace Negotiations: Saigon's Side of the Story. Christiansburg, Va.: Dalley Book Service, 2005.

- Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010.

- Phraxayavong, Viliam. History of Aid to Laos: Motivations and Impacts. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Mekong Press, 2009.

- Savada, Andrea Matles. Laos: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1995.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. A History of Laos. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Van Atta, Dale. With Honor: Melvin Laird in War, Peace, and Politics. Madison WI.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008.