Wrestling mask

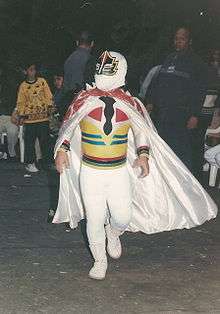

A wrestling mask is a fabric based mask that some professional wrestlers wear as part of their in-ring persona or gimmick. Professional wrestlers have been using masks as far back as 1915 and they are still widely used today, especially in Lucha Libre in Mexico.

History

At the 1865 World's Fair, Theobaud Bauer debuted the mask, wrestling as "The Masked Wrestler" in Paris, France. He continued wrestling using the mask throughout France as part of a circus troupe in the 1860s before moving on the United States in the early 1870s.[1]

In 1915 Mort Henderson started wrestling as the "Masked Marvel" in the New York area making him the first North American wrestler to perform with such a gimmick. In the subsequent years many wrestlers would put on a mask after they had been used in an area, or territory, that their popularity and drawing ability diminished, it would be an easy way for a wrestler to begin working in a new area as a "fresh face". Sometimes workers wore masks in one territory and unmasked in another territory in order to keep their two identities separate.

The mask in the US and Canada

Many wrestlers have had very successful careers while masked such as The Destroyer/Dr. X, Mr. Wrestling, Masked Superstar and the Spoiler. In the days where professional wrestling was more regional, with less national television coverage, it was not uncommon for more than one person or team to use the same gimmick and mask, and there have at times been several masked "Interns", "Assassins" and "Executioners" working simultaneously. Tag team wrestling has seen more masked teams, using identical masks to create unity between wrestlers. Successful masked teams include the Masked Assassins, Blue Infernos and the Grapplers.

One of the best-known North American masked wrestlers was Big Van Vader, who was also known for his in-ring agility despite his large frame during the 1980s and 90s. Other notable examples are Rey Mysterio, Mankind, Kane, Edge & Christian as 'Los Conquistadores' & Owen Hart as 'Blue Blazer'.

Today, masked wrestlers are not a common sight in the United States and Canada, but masked wrestlers have a long history in that region, dating back to 1915. A mask sometimes will be used by a well known wrestler in a storyline where they must get around various "stipulations" or betray a trust without revealing their true identity. For instance wrestlers who are suspended in a storyline return under a mask under another name, usually with it being very obvious who is under the mask. Examples of this include: Hulk Hogan as Mr. America, Dusty Rhodes as The Midnight Rider, André the Giant as Giant Machine, Brian Pillman as The Yellow Dog, The Miz as The Calgary Kid, Dan Marsh as Mr. X and Bo Dallas as Mr. NXT. Jimmy Valiant once returned under a mask as Charlie Brown from Outta Town after losing to Paul Jones in a "Loser Leaves Town" match (a stipulation where the loser of the match must resign from the organization for which he worked). Mickie James also revealed to be under the mask when she returned to WWE as Alexa Bliss's partner.

The mask in Lucha Libre

When I put on the mask, I'm transformed. The mask gives me strength. The mask gives me fame. The mask is magical. When I remove the mask, I'm a normal human who can walk right by you, and not even get a "hello". Usually with the mask on, everything is positive. Without the mask I'm a normal being who has his problems, who cries, who sometimes suffers. I could tell you that I really admire El Hijo del Santo. But do you know who I admire more ? The human being. Thanks to him, El Hijo del Santo has a life. And this human being sometimes sacrifices a lot to give this other identity life.

— El Hijo del Santo, [2]

It is a common misconception that masks in Lucha Libre spring from the Aztec, Inca or Mayan tradition but the mask, or "Máscara" in Spanish, was first introduced in Mexico when a promoter saw American wrestler "Cyclone" McKey working in Texas and decided to bring McKey to work for his promotion, Empresa Mexicana de la Lucha Libre (EMLL). The Mexican fanbase quickly took to the mystery of the masked man and soon after Mexican wrestlers themselves started wearing masks, becoming "Enmascarados". Early masks were simplistic with strong, basic colors designs that could be recognized even in the back row of the arena. Over the years the masks evolved to become very intricate and colorful drawing on Mexico's rich history. Unlike in other parts of North America the popularity of the masked wrestlers has not waned over the years, with souvenir masks being sold at events and online. In modern lucha libre, masks are colorfully designed to evoke the images of animals, gods, ancient heroes, and other archetypes, whose identity the luchador takes on during a performance. Most wrestlers in Mexico start their career wearing a mask, but over the span of their careers a substantial number of them will be unmasked. Sometimes, a wrestler slated for retirement will be unmasked in one of his final bouts or at the beginning of a final tour, signifying loss of identity as that character. Sometimes, losing the mask signifies the end of a gimmick with the wrestler moving on to a new gimmick and mask, often without public acknowledgement of the wrestler's previous persona.

The wrestling mask is considered "sacred", so much so that the intentional removal of a mask is grounds for disqualification. If a wrestler is unmasked during the match their top priority is to cover up their face and usually gets help from people at ringside to hide his face. Most masked wrestlers wear their masks for any and all public appearances using the mask to keep their personal life separate from their professional life. Because of the mask most Mexican wrestlers also enjoy a higher degree of anonymity about their personal life. Some wrestlers become larger than life characters such as El Santo, one of the most popular cultural icons who always wore his mask in public, revealed his face only briefly in old age, and was even buried in his trademark silver mask.

Luchas de Apuestas

In Lucha Libre the highest achievement is not winning a championship but winning the mask of an opponent in a "Luchas de Apuestas" match, a "bet fight" where each wrestler bets their mask. The Luchas de Apuestas match is usually seen as the culmination of a long and heated storyline between two or more wrestlers with the winner getting the "ultimate victory”. It is customary for the loser of such a match to reveal his real name, where he's from and how long he has been a wrestler before taking the mask off to show his face. Unmasked wrestlers will wager their hair instead, risking having his or her head shaved bald in case of defeat. There can be several reasons to book a "Luchas de Apuestas" match beyond the obvious purpose of elevating the winner. If the loser is a younger wrestler then the loss of the mask can sometimes lead to a promotional push after unmasking, or the wrestler is being given a new ring persona. Older wrestlers often lose their masks during the last couple of years of their career, often for a big payday depending on how long and successful a career they've had, The more successful the wrestler that's unmasked the bigger the honor for the winner.

The first luchas de apuestas match was presented on July 14, 1940 at Arena México. The defending champion Murciélago was so much lighter than his challenger Octavio that he requested a further condition before he would sign the contract: Octavio would have to put his hair on the line. Octavio won the match and Murciélago unmasked, giving birth to a tradition in lucha libre.[3]

High profiled "Luchas de Apuestas" include El Santo winning the mask of Black Spirit, Los Villanos winning the masks of all three Los Brazos (El Brazo, Brazo de Oro and Brazo de Plata), Atlantis winning the mask of Villano III, La Parka unmasking both Cibernético andad El Mesias, Villano V taking Blue Panther's mask and Último Guerrero winning the mask of Villano V. Some wrestlers have made a career by the volume of masks they have won rather than the general quality of their opponents—wrestler Super Muñeco claims to have won over 100 masks, with at least 80 verifiable "Luchas de Apuestas" wins, while Estrella Blanca is said to have the most Luchas de Apuestas with over 200 masks won.

The mask in Japanese wrestling

The Destroyer, an American, was the first masked wrestler to work in Japan during the 1960s but remained a novelty with very few Japanese wrestlers choosing to wear a mask. In the 1970s Mil Máscaras became the first Mexican Luchador to work on a regular basis and became very popular with the fans. The original Tiger Mask, Satoru Sayama was inspired by Mil Máscaras to create the masked "Tiger Mask" persona. After the success of Tiger Mask several wrestlers have adopted the mask, mainly lighter wrestlers who like Sayama had a more high flying and flashy style. The wrestling mask is held in more regard by the Japanese fans than the North American fans but isn't as "sacred" as the Mexican mask, meaning that the wrestler can perform both masked one day and unmasked another if he so wishes. Famous Japanese masked wrestlers include Jyushin Thunder Liger, Último Dragón, El Samurai, The Great Sasuke, Dragon Kid and Bushi.

Anatomy of the wrestling mask

The original wrestling masks were often masks attached to a top that snapped in the groin making it very uncomfortable for the people wearing it. If the masks were not attached to the top, then they were made from uncomfortable material such as brushed pig skin, leather or suede. In the 1930s, a Mexican shoe maker called Antonio Martinez created a mask on request from Charro Aguayo that became the standard for wrestling masks created since then. The basic design consists of four pieces of fabric sewn together to create the basic shape that covers the entire head. The mask has openings for the eyes, nose and mouth with colorful trim around the open features, this trim is known as "Antifaz" in Spanish. The back of the mask is open with a "tongue" of fabric under laces to keep it tight enough to not come off accidentally during a match. The first variation in style came when the jaw and mouth area was removed from the mask to expose the skin. Other masks have solid material over the mouth, nose, eyes or all three, in the case of fabric covering the eyes a stretched fabric that is see through up-close is used.

Originally being made from fabric masks have evolved and are now made from a variety of materials from cotton to nylon to various vinyls in many different colours and patterns. Several additions have been made to the mask decorations over the years with the most prevalent and visually striking being foam horns and artificial hair attached to the mask. Mock ears are also commonly used, especially if the mask has an animal motif such as a tiger.

See also

Further reading

- Enciclopedia de las Mascaras, 11 volume magazine published 2007 - 2008. Covers the technical aspects of various luchador's masks from A to Z, details on fabric, construction, design and manufacturing.

References

- General

- Madigan, Dan (2007). Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre & honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- El Nacimiencito de un Sueño (the birth of a dream), Pages 41 - 51

- Masks, Pages 46-49

- The Mask in the match, Pages 60-61

- Los Enmascarados (the Masked Men), Pages 71-127

- Ranjan Chhibber (2007). "Lucha in the '80s and the demise of the masked Mexican wrestler in America". Mondo Lucha Libre: the bizarre & honorable world of wild Mexican wrestling. HarperColins Publisher. pp. 133–137. ISBN 978-0-06-085583-3.

- L.L. Staff (2007-11-05). "Lucha Libre: Revista de Mascaras" (in Spanish). Mexico. pp. 1–65. Mascareros Forjadores de Leyendas.

- Stacy Brandt (2002-12-05). "Who Was That Masked Man?". The Daily Aztec. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Greg Oliver & Steve Johnson (2005). The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-683-6.

- The Assassins, Pages 52-54

- The Interns, Pages 76-78

- The Infernos, Pages 199-201

- The Mysterious Medics, Pages 213-215

- Mr. Wrestling I & II, Pages 231-232

- Specific

- Shoemaker, David (2013). The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling. Penguin. p. 69. ISBN 1592407676.

- ESPN Interview Born + Raised: El Hijo del Santo Spanish version

- Lourdes Grobet; Alfonso Morales; Gustavo Fuentes & Jose Manuel Aurrecoechea (2005). Lucha Libre: Masked Superstars of Mexican Wrestling. Trilce. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-933045-05-4.