Worthington Corporation

The Worthington Corporation was a diversified American manufacturer that had its roots in Worthington and Baker, a steam pump manufacturer founded in 1845. In 1967 it merged with Studebaker and Wagner Electric to form Studebaker-Worthington. This company was in turn acquired by McGraw-Edison in 1979.

The Worthington "Flying W" logo | |

| Industry | Manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Fate | Merged |

| Successor | Studebaker-Worthington |

| Founded | 1845 |

| Founder | Henry Rossiter Worthington |

| Defunct | 1967 |

| Headquarters | United States |

Worthington Pump Works (1845–1899)

Worthington and Baker, manufacturers of hydraulic machinery such as steam pumps and meters, was founded by Henry R Worthington and William H. Baker.[1] Worthington was the inventor of the direct acting steam pump.[2] The first foundry was near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In 1854 the partners moved to Van Brunt Street in Brooklyn. The partnership was dissolved around 1860 when Baker died.[1] A new partnership called Henry R. Worthington, or Worthington Hydraulic Pump Works, was formed in 1862.[1]

The United States Navy used Worthington pumps to pump: boiler feed water, bilge water, fire fighting, and general services (https://www.asme.org/about-asme/engineering-history/landmarks/262-worthington-steam-pumps-uss-monitor) aboard various ships during the American Civil War (1861–1865), including the USS Monitor.[3] After Henry Worthington died in 1880 he was succeeded by his son Charles Campbell Worthington (1854–1944). While head of the company, Worthington contributed many useful improvements to pumps, compressors, and other machines.[4] The company moved from Brooklyn to Harrison, New Jersey in 1904.[1]

In 1885 the Worthington Pumping Engine Company, representatives of Worthington pumps of the US, obtained an order from the British Army to deliver ten high-pressure pumps to deliver water needed by the British Expeditionary army coming to the aid of General Gordon in Khartoum, Sudan.

The British pump suppliers could not deliver the pumps fast enough. The British company James Simpson & Co. learned of the Worthington company because of this order, and on 13 December 1885 signed an agreement with the Worthington Pumping Engine Company under which they gained exclusive manufacturing rights for Worthington pumps in Britain.[5] The British company's pumps were sold in the English and Colonial markets.[6][lower-alpha 1]

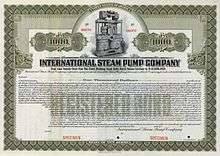

International Steam Pump Company (1899–1916)

Benjamin Guggenheim was a member of a family that had made a fortune in the smelting business in the United States, largely through his efforts, and that controlled the American Smelting and Refining Company.[9] Guggenheim founded the International Steam Pump Company (ISPC).[10] The ISPC was organized by the Seward legal firm in 1899. Lehman Brothers were the bankers.[11]

The ISPC merged Blake and Knowles Steam Pump Works, Ltd. (BKSPW), Worthington Pump Works and other companies that together made up a large part of total American capacity for making steam pumps.[12] The company's products were diverse, including the elevators for the Eiffel Tower.[10] Worthington Pump Works was the largest of the merged firms.[13] Charles Campbell Worthington was president of the company until he retired in 1900.[14] Guggenheim became president of the ISPC.[9] The ISPC soon ran into financial difficulties, and Guggenheim invested increasing amounts of capital to keep it afloat.[10]

BKSPW had been registered in England in 1890 with a capital of £300,000 to purchase in full the George F. Blake Manufacturing Company and the Knowles Steam Pump Works, with three plants in the United States.[12] In its 1901 Annual Report the ISPC reported holding £200,000 of ordinary shares in BKSPW. The George F. Blake Manufacturing Company, an ISPC subsidiary, had liabilities that included $1 million of mortgage bonds and $500,000 of preferred stock of BKSPW. The ISPC 1904 Annual Report noted that BKSPW had been dissolved in 1903, replaced by a company with the same name based in New Jersey.[15] An October 1908 description of the Blake-Knowles Steam Pump Works in Cambridge, Massachusetts, part of the International Steam Pump Company, said it was the second largest of its kind in the United States, employing more than 1,700 men.[16]

In 1903 Guggenheim founded a factory in Milwaukee to manufacture mining machinery. In 1906 it was merged into the ISPC.[9] By 1909 the ISPC as a whole was employing 10,000 men.[9] In May 1910 Benjamin Guggenheim reported strong results with net earnings of about $2 million and profits of about $700,000. The company had purchased the JeanesvilIe Iron Works Company and had obtained a controlling interest in the Denver Rock Drill and Machinery Company, adding at least 30% to capacity.[17] The Holly Manufacturing Company (1859–1912) was acquired in 1912.[18]

Guggenheim was a passenger on RMS Titanic and died on 15 April 1912 when the ship sank.[19] The International Steam Pump Company went into receivership in 1914. A plan of reorganization was issued on 5 August 1915 and under this plan the firm was reorganized in 1916 as the Worthington Pump & Machinery Corporation.[20]

Worthington Pump and Machinery Corporation (1916–1952)

The Worthington Pump and Machinery Corporation had subsidiaries in Buffalo, New York, Holyoke, Massachusetts, Cincinnati, Ohio and London, England.[18] In 1917 the independent but associated British Worthington Pump Co. changed its name to Worthington Simpson.[7] The Worthington Pump and Machinery Corporation purchased a stake in Worthington-Simpson in 1933.[8]

Worthington Corporation (1952–1967)

In 1952 the company became the Worthington Corporation.[18] As of 1956 the Worthington Corporation had laboratories in Harrison, Holyoke, and Buffalo. The labs employed five chemists, forty engineers, four mathematicians, four metallurgists, two physicists and thirty five others. They conducted research into hydrodynamics, thermodynamics, mechanics and materials.[21]

In 1964 Worthington purchased the American Locomotive Company (Alco).[22]

Merger with Studebaker (1967)

In 1967 a merger with Studebaker was arranged by the entrepreneur Derald Ruttenberg.[23] He took the risk of buying Studebaker despite the liabilities that came with it, including dealer warranties and union agreements. He saw that Onan generators and STP engine additives were healthy businesses. The large tax loss was also valuable. Worthington was expected to continue to earn steady profits, but could use the tax loss to avoid paying taxes.[24] The stockholders of Studebaker and Worthington approved the merger despite rumors that the Federal Trade Commission considered the merger would be "substantially anti-competitive".[25] Studebaker was acquired by Wagner Electric, which in turn was merged with Worthington Corporation to create Studebaker-Worthington.[26]

The merger was completed in November 1967, creating a company with $550 million of assets.[27] The former chairman of Worthington, Frank J. Nunlist, was appointed president and chief executive officer.[25] Randolph Guthrie of Studebaker was chairman of the new company.[28]

McGraw-Edison purchased Studebaker-Worthington in 1978. McGraw-Edison was in turn acquired by Cooper Industries in 1985.[29]

References

Notes

Citations

- Worthington Hydraulic Pump Works, EMJ.

- Max McGraw Foundation.

- Quarstein 2010, p. 172.

- Maurer 1999, pp. 1-2.

- Roberts 2006, p. 158.

- Worthington 1887, p. 139.

- James Simpson and Co: Grace's Guide.

- A History of Excellence: Flowserve.

- Hines 2011, p. 61.

- Davis 1994, p. 204.

- Swaine 1946, p. 633.

- Wilkins 1989, p. 428.

- Chandler 2009, p. 198.

- Maurer 1999, p. 1.

- Wilkins 1989, p. 836.

- Blake-Knowles Steam Pump Works 1908.

- Steam Pump Has Good Year 1910.

- Worthington Corporation Records, 1859–1960.

- Hines 2011, p. 46.

- Swaine 1946, p. 196.

- Mauk 1956, p. 521.

- Engineering Corporation Acquires Alco Products Railway Transportation October 1964 page 8

- Worthington to merge Railway Age July 31, 1967 page 64

- Weir 2008, p. 85.

- Studebaker, Worthington Vote Merger.

- Studebaker History Timeline.

- Churella 1998, p. 144.

- Foster 2008, p. 187.

- Bonsall 2000, p. 396.

Sources

- "A History of Excellence" (PDF). Flowserve. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- "Blake-Knowles Steam Pump Works". Cambridge Sentinel. 4 (52). 31 October 1908. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- Bonsall, Thomas E. (2000). More Than They Promised: The Studebaker Story. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3586-5. Retrieved 2013-10-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, Alfred D (2009-06-30). Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02938-5. Retrieved 2013-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Churella, Albert (1998-08-03). From Steam to Diesel: Managerial Customs and Organizational Capabilities in the Twentieth-Century American Locomotive Industry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2268-3. Retrieved 2013-10-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, John H. (1994-08-01). The Guggenheims: An American Epic. SP Books. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-56171-351-6. Retrieved 2013-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Gerry Hempel (2011-11-16). Romancing the Roads: A Driving Diva's Firsthand Guide, East of the Mississippi. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-58979-620-1. Retrieved 2013-10-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster, Patrick (2008). Studebaker: The Complete History. MotorBooks International. ISBN 978-1-61673-018-5. Retrieved 2013-10-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hines, Stephen (2011-09-01). Titanic: One Newspaper, Seven Days, and the Truth That Shocked the World. Sourcebooks, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4022-5667-7. Retrieved 2013-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "James Simpson and Co". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- Mauk, James F. (1956). Industrial research laboratories of the United States. National Academies. NAP:14697. Retrieved 2013-10-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maurer, Joe (September–October 1999). "C. C. Worthington and the Worthington Mower". Gas Engine Magazine. Ogden Publications, Inc. Retrieved 2013-10-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Max McGraw". Max McGraw Foundation. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- Quarstein, John V. (2010). The Monitor Boys: The Crew of the Union's First Ironclad. The History Press. ISBN 9781596294554.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Gwilym (2006-01-01). Chelsea to Cairo-- 'Taylor-made' Water Through Eleven Reigns and in Six Continents: A History of John Taylor & Sons and Their Predecessors. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-3411-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Steam Pump Has Good Year". The New York Times. 12 May 1910. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- "Studebaker History Timeline". StudebakerHistory.com. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- "Studebaker, Worthington Vote Merger Despite Antitrust". The Montreal Gazette. 16 November 1967. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- Swaine, Robert T. (1946). The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors, 1819-1947. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-713-7. Retrieved 2013-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weir, William (2008-02-01). History of the Weir Group. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-886-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkins, Mira (1989). The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard University Press. p. 836. ISBN 978-0-674-39666-1. Retrieved 2013-10-28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Worthington Corporation Records, 1859–1960". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- Worthington, Henry R. (1887). The Worthington Steam Pumping Engine: History of Its Invention and Development... Retrieved 2013-10-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Worthington Hydraulic Pump Works". Engineering and Mining Journal. 76. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

External links

![]()

- Worthington Compressor Services, OEM, services and parts company, legacy spin-off established in 2012