Workmen's Village, Amarna

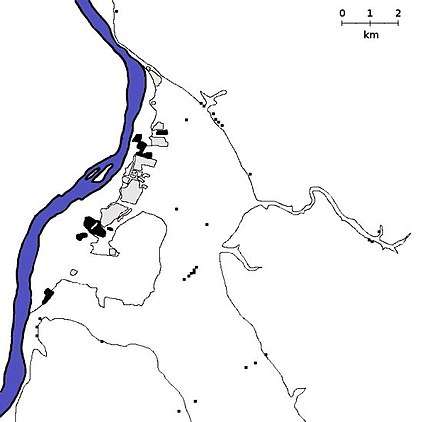

Located in the desert 1.2 km east of the ancient city of Akhetaten, the Workmen's village was built during the reign of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Akhenaten. It housed the workers who constructed and decorated the tombs of the city's elite, making it comparable to the better studied Theban workers village of Deir el-Medina.[1] While today an isolated part of the Akhetaten site, the Workmen's Village helps provide many well preserved artifacts and buildings allowing archaeologists to gather much information about how the society functioned.

Excavation history

The Workmen's Village has been known since the surveys of Petrie[2] but was first excavated in 1921 by the Egypt Exploration Society. At this time it was known as the Eastern Village. Two seasons of excavation were undertaken by T. Eric Peet and Leonard Woolley; the first season excavated four houses as a test of the site and the second season excavated approximately half of the village.[3][4] Some of the tomb chapels that surround the village were also excavated.[5] The Egypt Exploration Society resumed excavations in 1979 led by Barry Kemp and concluded in 1986. These excavations focused on the areas immediately surrounding the walled village.[4]

Walled village

The village is located on the floor of a Y-shaped valley. The South Tombs, which are within easy walking distance, are the only part of the city directly visible from this isolated location.[6] The walled village from which the settlement takes its name occupies an area of approximately 70 square meters and is surrounded by an outer wall 75 to 80 cm thick. It has a single entrance on the southern side and is divided into two unequal halves by an equally thick inner wall.

73 houses of identical size are found inside this area, with one larger house with its own garden that presumably belonged to an official overseer.[7][3] Each house was five meters wide and 10 meters long, and constructed of mud brick with some stone used around the base of the walls. Thresholds were often made of cut stone but no stone walls were found. The interior was divided into four main rooms: the "entrance hall", "living room", "bedroom", and "kitchen". Stairs, located either in front or rear of the house, led up to a second floor. In some houses the walls had been preserved to a height of 1.8 meters. Windows are not preserved but were likely small and high up to let in light but minimize dust. The interiors were once decorated but little survives. Panels of colour were found to begin about 20 from the floor in some houses. The best preserved decoration depicts dancing figures of Bes along with the goddess Taweret, and in a separate house a scene of women and girls who may be musicians or dancers.[8][9] Finds from within the houses are consistent with everyday life: amulets, beads, fragments of matting, spindle-whorls, rings, headrests, and pottery.[10]

The village contains no well so water along with food stuffs and animal fodder must have been brought in from the city. The likely distribution point is close to a building on the edge of town that probably served as a checkpoint.[11] There is evidence that animals where kept both inside and immediately outside the village. This evidence comes in the form of animal pens in the south-western part of the village and mangers in the main street,[12] as well as buildings directly in front of the village and to the east. The remains of cow, pig, and goat were found in the rubbish dumps. The limited range of cattle bones recovered indicates that joints of beef were likely part of the rations and that they were not being raised on-site.[13] Pigs, fed grain, were raised in covered pens, and goats, fed vegetable material, were raised in separate areas surrounding the village. The inhabitants also made attempts to garden in the areas below and between the chapels outside the village. The fact the villagers were going to such efforts to try to be partially self-sufficient indicates that the state had a limited role in providing for the needs of the people. It can be postulated that the villagers used the animals they raised to pay for the extra water and grain needed for the animals.[14]

Chapels and their wall paintings

Outside of the walled portion of the village approximately 23 chapels were built along the hillside. These chapels are generally composed of mud brick and limestone for their construction and varied considerably in their layout. The essential features found in the more complex examples were an outer court, an inner court, and a shrine with niches.[5] Comparison with the chapels at Deir el Medina clarify the purpose of the chapels in this village. They appear not to have been built as funerary chapels initially, but as places where divinities or family members could be worshiped, and as places where special meals could be prepared and eaten. Deliberate cut marks have been found on the floors and benches of the Main Chapel; it is possible this is a result of people obtaining holy dust for inclusion in spells or potions or they were made by javelins in an effort to absorb holy power. This is suggested by the find of a bronze javelin in the Outer Hall of the Main Chapel.[15]

The Main Chapel

The Main Chapel, located to the southeast of the walled village, is the largest and best understood, having been protected from robbers by piles of spoil from the excavations in the 1920s. It was built in the last stage of the occupation of the village, during the reign of Tutankhamun given it partly overlies earlier construction in the stratigraphy. The structure had two entrances: a formal one to the east and another further to the south which was probably for everyday use. The formal entrance seems to have had a pylon structure, while the southern entrance was approached by a line of T shaped basins set into the ground. The chapel had several annexes for cooking and for housing animals.[16][17]

This chapel is most well known for its colourful paintings which survive as fragments. Vultures grasping shen-rings and feather fans, winged sun discs, and lotus bouquets survive.[17]

The purpose for the chapels was to, according to British archaeologist and researcher Fran Weatherhead, “experience a sense of communion with spirits”.[18] In context, the presence of the chapels across the village helps bring its people opportunities of making offerings for both their deities and also recently deceased loved ones as evidenced by the fact the majority of the chapels are built merely close to a rather large area of tombs north of said chapels. Therefore, the notion of recently deceased loved ones entering the afterlife justifies the presence of an offering altar within the main chapel in which implies the others housing similar looking altars for a very similar purpose. Ultimately, a distinction between every one of these chapels comes in both the deities worshiped and their respected symbols painted on the walls.

Significance of this village

In general, the site of Akhetaten dedicates the vast majority of wall painting to not only displaying the royal family alongside the Aten but also to showcasing the daily lives of the citizens as being prosperous, joyful, and above all lively. Since the majority of these depictions in the main city are destroyed with very little fragments left behind, the Workmen's Village's greater preservation provides a better chance for archaeologists to understand everyday life during the Amarna period.

Religious significance

During Akhenaten's reign, the god Aten was elevated above all others. The worship of other gods was suppressed and their temples closed. The god Amun received the harshest treatment, with his name eventually being hacked out where it occurred. Akhenaten's devotion to the Aten culminated with his reforms of Egyptian religion in the cult of the royal family who are the sole intermediaries between the populace and the Aten and the founding of the city of Akhetaten. It appears that the general population continued their traditional worship of household gods like Bes and Taweret, with amulets of both and a stele of Taweret being found in the city itself.[19] To this end it is interesting to note that the name of Amun appears in painted fragments from the Main Chapel and another, Chapel 529. The fragments from the Main Chapel are in the "Htp-di-nswt" format and call Amun the "good ruler eternally, lord of heaven, who made the whole earth."[20] Additionally, a wooden top for a military standard depicting Wepwawet was found in the sanctuary.[21] In Chapel 525 two stelae were found. The smaller of the two depicts the god Shed, who is called "the great god, the Lord of the Two Lands", while the larger one addresses funerary prayers to Shed and the goddess Isis in addition to the Aten. This larger stele is inscribed for a man named Ptah-may, who is the "praised one of the Living Aten", and his family. Peet and Woolley suggested that the worship of the traditional gods continued throughout the reign of Akhenaten, and that the distance separating the Workmen's Village from the main city afforded it more freedom in this regard. They also interpret the name of Amun being present as an indication that the decoration dates to the early reign of Tutankhamun, when orthodoxy was returning.[20]

References

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 51–52. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Petrie, W. M. Flinders (1894). Tell el-Amarna. London: Methuen & Co. pp. 4-5.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 51–91. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1987). "The Amarna Workmen's Village in Retrospect". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 73: 21.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 92–108. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1984). Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1984). Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 55–65. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1979). "Wall Paintings from the Workmen's Village at El-'Amarna". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 65: 47–53.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 65–91. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1984). Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 6–8. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1984). Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. p. 9. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1987). "The Amarna Workmen's Village in Retrospect". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 73: 36–41.

- Bomann, Ann (1984). "Chapter 2: Report on the 1983 Excavations: Chapel 561/450 (The "Main Chapel")". In Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 30–33. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Kemp, Barry J. (1984). Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 10–13. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Bomann, Ann (1984). "Chapter 2: Report on the 1983 Excavations: Chapel 561/450 (The "Main Chapel")". In Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 14–27. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Weatherhead, Fran (2007). The main chapel at the Amarna Workmen's Village and its wall paintings. London, United Kingdom: Egypt Exploration Society. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-85698-186-9.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. p. 25. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Peet, T. Eric; Woolley, C. Leonard (1923). The City of Akhenaten Part I: Excavations of 1921 and 1922 at El-'Amarneh. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 91–99. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Bomann, Ann (1984). "Chapter 2: Report on the 1983 Excavations: Chapel 561/450 (The "Main Chapel")". In Spencer, A. J. (ed.). Amarna Reports I (PDF). London: The Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 27–30. Retrieved 2 October 2019.