Workers Alliance of America

The Workers Alliance of America (WAA) was a Popular Front era political organization established in March 1935 in the United States which united several efforts to mobilize unemployed workers under a single banner. Founded by the Socialist Party of America (SPA), the Workers Alliance was later joined by the Unemployed Councils of the USA, a mass organization of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), and by the National Unemployed Leagues originating with A.J. Muste's Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) and successor organizations.

The WAA was initially headed by Socialist David Lasser, but the organization gradually came to be dominated by the CPUSA, which had superior size and organizational discipline compared to its partners. Originally resembling a trade union for relief workers employed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), in its later incarnation it came to resemble a political pressure group focused upon winning additional funding of the WPA by a budget-conscious Congress.

The organization rapidly atrophied after 1939, in the wake of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and the eruption of World War II in Europe and was terminated in 1941.

Organizational history

Background

The early 1930s were marked by extreme hostility between the various political parties of the American left wing, including most notably the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and the Socialist Party of America (SPA). Under the so-called Third Period line of the Communist International, the Communists vigorously and aggressively attacked the Socialists at every turn as so-called "social fascists" — ideological fellow travelers who both enabled and advanced a fascist agenda as a de facto wing of the international fascist movement.[1] The Socialists responded to hostility with hostility of their own, bitterly asserting that the American Communist Party was no more than a deceitful and manipulative appendage of Soviet foreign policy, advancing the agenda of a nation headed by an anti-democratic dictator in the person of Joseph Stalin.

The rise to state power of the Nazi Party in Germany and the brutal repression of Socialists and Communists which followed shaped the attitudes of both the Communist and Socialist movements. A new turn to united front efforts on the part of the Communists began in 1934, culminating with the 7th World Congress of the Comintern in the summer of 1935, which explicitly endorsed cooperation with non-communists in an effort to undermine and roll back fascism. Cooperation in joint political ventures, including participation of non-communist leaders, became the order of the day.

Late in 1933 and into 1934 the Communists had made overtures to rank-and-file activists in Socialist-led unemployed worker organizations to "build the united front in spite of your leaders" and to forge unity "over the heads of...splitting leaders."[2] Now the so-called "united front from below" would be set aside and real efforts made to engage in joint work with Socialist-led organizations, beginning with the convocation of a National Congress for Unemployment and Social Insurance by the CPUSA in January 1935.[2] While this initial activity drew only limited participation from the Socialists early in the planning process and was boycotted by the fledgling American Workers Party headed by A. J. Muste, the stage was set for future joint work on the unemployment issue.[2]

The Workers Alliance of America would ultimately prove to be the umbrella organization bringing these three political entities — the Communists, Socialists, and "Musteites" — together for joint work.

Establishment

The Workers Alliance of America (WAA) was actually a venture of the Socialist Party of America in its earliest incarnation.[2] An inaugural convention was held early in March 1935, chaired by Socialist David Lasser, head of the New York Workers Committee on Unemployment.[2] Lasser had in previous years rebuffed unity overtures of the Communist Party, but delegates to the WAA's founding convention received Communist Party Unemployed Councils leader Herbert Benjamin warmly, responding to his plea for organizational unity with an ovation.[2] Following Benjamin's speech a formal resolution of the convention criticizing the Unemployed Councils of the USA as pawns of the Communist party was withdrawn.[2] Growing sentiment for unity was apparent.

The resolutions of the founding convention of the Workers Alliance were presented at the White House by Lasser on March 4, 1935.[3] Chief among these were a call for adoption of a 30-hour work week without reduction of wages and universal unemployment insurance, to be paid for with taxes on gifts and incomes greater than $5,000 per year as well as worker representation on all committees established for the purpose of administering social insurance.[3]

Development

Headquarters of the WAA was initially established in the Socialist Party bastion of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[4] Immediately after the group's formation clearly inflated membership figures began to appear in the press, including an absurd and grandiose March 1935 claim that the fledgling organization was backed by a membership of 450,000 people in 28 states.[4] David Lesser was named President of the organization, with Paul Rasmussen of Milwaukee in charge of day-to-day operations as the group's National Secretary.

Despite such patently obvious misstatements of membership size, the WAA did immediately begin constructive work with top officials of the American Federation of Labor (AF of L) with respect to standards and practices relating to Depression-related unemployment relief. In April 1935 WAA Chairman Lasser announced that agreement had been reached with AF of L President William Green relating to the organization of workers employed through the government's $4.8 billion work relief program with a view to the unionization of those so employed.[5] The joint program of the WAA and AF of L was said to include payment of union scale for all skilled workers, a minimum payment of $30 per week for all workers on relief, and provision for collective bargaining for all workers on work-relief projects.[6]

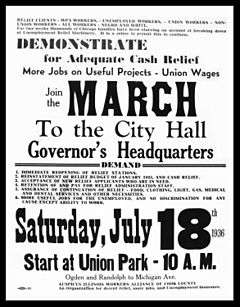

Existing local and state workers' relief organizations began to change their names to match that of the new national organization during the rest of 1935, exemplified by the Wisconsin Workers Committee changing its name to the Wisconsin Workers Alliance in becoming the state affiliate of the WAA.[7] State groups retained autonomy of action in pushing state and local governments towards unemployment relief, with the Illinois Workers Association issuing a call for a Hunger March at the state capitol in Springfield to its 226 local affiliated groups for May 21–22, 1935 — a call endorsed after the fact by National Secretary Rasmussen on behalf of the national Workers Alliance organization.[8]

Together with officials of organized labor, the WAA was also active in the summer of 1935 in coordinating strikes of workers in New York and Pennsylvania employed by the federal government's Works Progress Administration (WPA) over what were deemed to be inadequate wages for employees engaged in WPA work-relief projects.[9]

1936 merger

Unity negotiations between the three parties — the Workers Alliance of the Socialists, the Unemployed Councils of the Communists, and the National Unemployed Leagues of the Musteite movement — began in April 1935.[2] A full year of negotiations would follow, with no merger achieved between the Workers Alliance and the Unemployed Councils until April 1936.[10] As a condition of unification, the Communists were forced to surrender their old organizational name and to accept the Workers Alliance's title.[11] The CPUSA was also force to accept a minority of seats on the governing Executive Board of the organization, which retained Socialist Lasser as National Chairman and Communist Benjamin as Organizational Secretary.[11]

The Communist Party's Unemployed Councils organization shared the WAA's propensity for public assertion of inflated membership rolls, claiming a membership of 300,000 in 1935 and 600,000 in 1936 just prior to the Unity convention.[12] These farcical totals were belied by a more sober estimate which Herbert Benjamin privately provided to the Politburo of the CPUSA at the time of the 1936 merger, at which he state the membership of the Unemployed Councils as 8,500 and estimated the dues paying membership of the Workers Alliance in the range of 15,000 to 20,000.[12]

The day after the Unity Convention some 500 members and sympathizers of the WAA marched to the White House, their line of march watched by 100 police officers.[13] The marchers, parading under red banners, called for launch of a new $6 billion work-relief program, with David Lasser and four other members of the national committee granted a 30-minute audience with Presidential secretary Marvin McIntryre.[13] Following the meeting Lasser declared to the press his growing dissatisfaction with President Roosevelt, who he felt was sacrificing the interests of the unemployed to the expediencies of his 1936 reelection campaign.[13] "We told [McIntyre] that we were tired of Mr. Roosevelt's promissory notes, always being renewed and renewed again, with indefinite dates," Lasser declared.[13]

Historian Harvey Klehr indicates that membership of the WAA did exhibit growth after unification, however, in large measure as a result of growth of the WPA jobs program and the ability of now employed WPA workers to pay the relatively nominal dues of the WAA.[12] Despite misgivings about painting itself into a corner as a de facto trade union for WPA employees, it seems that in practice the WAA became exactly that, with WPA employees constituting some 75 percent of the organization's dues paying membership by 1939.[12] The survival of the WAA was thus intimately linked with the fate of the WPA program, with periodic layoffs of WPA workers due to budgetary constraints playing havoc with the WAA's membership rolls.[14]

The WAA unsurprisingly dedicated a great deal of its political effort to pushing Congress and the Roosevelt Administration to reverse cuts to the WPA budget and to renew financial commitment to relief efforts on behalf of the unemployed.[14] A National Jobs March was called by the WAA during the summer of 1937, but the response was tepid, with only 2,500 people joining the temporary city constructed in WPA-supplied tents near the Lincoln Memorial.[14] Steady rain further demoralized the strikers, who quietly demonstrated outside the White House and Capitol before fading away.[15]

Official organs

The WAA published an official organ in the form of a newspaper published in Milwaukee called The Workers Alliance.[16] At least 18 issues were produced from the publication's launch on August 15, 1935 and September 1936.[16]

A second publication, Work, was launched in Washington, DC on April 9, 1938, with publication continuing at least through November 1940.[16]

Demise and legacy

The disintegration of the size and strength of the Socialist Party of America as a result of factional warfare stood in marked contrast to the expansion in size of the Communist Party in connection with its nominally patriotic and democratic political line expounded in its slogan "Communism is 20th Century Americanism," and the relative influence of the two organizations waned and waxed accordingly. By 1938 the WAA was thoroughly dominated by the Communist Party, effectively becoming an appendage of that organization.[17]

In its final years the WAA evolved into something resembling a typical political pressure group, publicly pushing the WPA's agenda for greater levels of funding.[18] Communist Party General Secretary Earl Browder would later romanticize the WAA's place in the political process, declaring

"Whenever the WPA had an appropriation up, Congress would shave it down to half. Then we would put on demonstrations in six cities; Congress would bring it up to two-thirds. We'd put on another series of demonstrations and they'd get their appropriation."[19]

Both the Communist Party and the Roosevelt administration had new and more important agendas as the 1930s came to a close, with the Communists and the administration thoroughly alienated from one another with the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in the summer of 1939 and the subsequent eruption of World War II in Europe. While the WPA would nominally continue until 1943, the Workers Alliance of America would be terminated in 1941.

The archives of the Workers Alliance of America are housed at the University of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[20] Included in the collection are the papers of David Lasser as well as copious files on the organization assembled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States Justice Department.[20]

Conventions

| Convention | Location | Date | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Founding Convention | Washington, DC | March 1935 | |

| 2nd (Unity) Convention | Washington, DC | April 7–10, 1936 | Unification of WAA with the CPUSA's Unemployed Councils and CPLA's National Unemployed Leagues. Attended by "several hundred" delegates. |

| 3rd Convention | Milwaukee, WI | 1937 | |

| 4th Convention | Cleveland, OH | 1938 | |

| 5th Convention | Chicago, IL | 1940 | |

Footnotes

- See, for example: Earl Browder, The Meaning of Social-Fascism: Its Historical and Theoretical Background (Workers Library Publishers, 1933); D.Z. Manuilsky, Social Democracy — Stepping Stone to Fascism (Workers Library Publishers, 1934). For an analysis of the origins of the theory, see Theodore Draper, "The Ghost of Social-Fascism," Commentary, Feb. 1969, pp. 29-42.

- Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984; pg. 295.

- United Press, "Call at White House to Petition President," Oshkosh [WI] Daily Northwestern, March 5, 1935, pg. 11.

- "Local Unemployed Association to Join State Union," Edinburg [IN] Daily Courier, March 21, 1935, pg. 1.

- Associated Press, "Proposes to Form Relief Man Union: Organization of Work Relief Personnel May Be Attempted," Hope [AR] Star, April 16, 1935, pg. 1.

- United Press International, AFL May Unionize Men on Work-Relief," Jefferson City [MO] Post-Tribune, April 15, 1935, pg. 2.

- "Workers' Group Changes Name: Will Be Known as Alliance to Conform with State Association," Racine [WI] Journal-Times, April 30, 1935, pg. 4.

- Associated Press, "Issue Call for State Hunger March May 22," Decatur Herald, May 16, 1935, pg. 2.

- "Urges Continued War on WPA Wage: National Organizer Keystone Workers' Speaker," Reading [PA] Times, Sept. 25, 1935, pg. 2.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pp. 295-296.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 296.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 297.

- "Hunger March Holds Parade: Red Banners are Carried Down the Streets of the Capital," Daily Chronicle [DeKalb, IL], April 11, 1936, pg. 1.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 298.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pp. 298-299.

- Chad Alan Goldberg, ""Contesting the Status of Relief Workers During the New Deal: The Workers Alliance of America and the Works Progress Administration, 1935-1941," Social Science History, vol. 29, no. 3 (Fall 2005), pg. 362. Both of these publications are available on microfilm through Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 303.

- Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pg. 299.

- Earl Browder, Letter to Theodore Draper of Oct. 10, 1955; cited in Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism, pp. 299-300.

- "Workers Alliance of America Records: Online finding aid," University of Pittsburgh Library System Service Center, Pittsburgh, PA, April 2007.

Further reading

- Edwin Amenta, Bold Relief: Institutional Politics and the Origins of Modern American Social Policy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Edwin Amenta and Drew Halfmann, "Wage Wars: Institutional Politics, WPA Wages, and the Struggle for U.S. Social Policy," American Sociological Review, vol. 65, no. 4 (Aug. 2000), pp. 506–528. In JSTOR

- Franklin Folsom, Impatient Armies of the Poor: The Story of Collective Action of the Unemployed, 1808-1942. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1991.

- Chad Alan Goldberg, ""Contesting the Status of Relief Workers During the New Deal: The Workers Alliance of America and the Works Progress Administration, 1935-1941," Social Science History, vol. 29, no. 3 (Fall 2005), pp. 337–371.

- Chad Alan Goldberg, "Haunted by the Specter of Communism: Collective Identity and Resource Mobilization in the Demise of the Workers Alliance of America," Theory and Society, vol. 32, no. 5/6 (Dec., 2003), pp. 725–773. In JSTOR

- Stanley High, "Who Organized the Unemployed?" Saturday Evening Post, vol. 211, no. 24 (Dec. 10, 1938), pp. 8–9, 30-36.

- Harold R. Kerbo and Richard A. Shaffer, "Unemployment and Protest in the United States, 1890-1940: A Methodological Critique and Research Note," Social Forces, vol. 64, no. 4 (June 1986), pp. 1046–1105.

- Harold R. Kerbo and Richard A. Shaffer, "Lower Class Insurgency and the Political Process: The Response of the U.S. Unemployed, 1890-1940," Social Problems, vol. 39, no. 2 (May 1992), pp. 139–115.

- Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward. Poor People's Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. New York: Vintage, 1978.

- Roy Rosenzweig, "Radicals and the Jobless: The Musteites and the Unemployed Leagues, 1932–1936." Labor History, vol. 16, no. 1 (Winter 1975), pp. 52–77.

- Roy Rosenzweig, "'Socialism In Our Time': The Socialist Party and the Unemployed, 1929–1936." Labor History, vol. 20, no. 4 (Fall 1979), pp. 485–509.

- James E. Sargent, "Woodrum's Economy Bloc: The Attack on Roosevelt's WPA, 1937-1939," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 93, no. 2 (April 1985), pp. 175–207. In JSTOR

- Helen Seymour, The Organized Unemployed. PhD dissertation. University of Chicago, 1937.

External links

- "Workers Alliance of America Records: Online finding aid," University of Pittsburgh Library System Service Center, Pittsburgh, PA, April 2007.