William de Chesney

William de Chesney (flourished 1142–1161) was an Anglo-Norman magnate during the reign of King Stephen of England (reigned 1135–1154) and King Henry II of England (reigned 1154–1189). Chesney was part of a large family; one of his brothers became Bishop of Lincoln and another Abbot of Evesham Abbey. Stephen may have named him Sheriff of Oxfordshire. Besides his administrative offices, Chesney controlled a number of royal castles, and served Stephen during some of the king's English military campaigns. Chesney's heir was his niece, Matilda, who married Henry fitzGerold.

William de Chesney | |

|---|---|

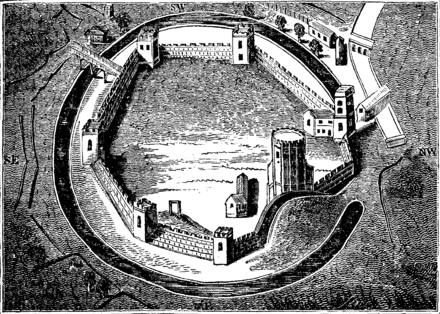

Ancient plan of Oxford Castle, according to a 19th-century engraving. Chesney held Oxford Castle during Stephen's reign. | |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret de Lucy |

| Relations | niece and heiress Matilda |

Background

Following King Henry I's death in 1135, the succession was disputed between the Henry's nephews—Stephen and his elder brother, Theobald II, Count of Champagne—and Henry's surviving legitimate child Matilda, usually known as the Empress Matilda because of her first marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry V. Matilda's brother, and King Henry's only legitimate son, William died in 1120, leaving Matilda as Henry's only legitimate offspring.[lower-alpha 1] After Matilda was widowed in 1125, she returned to England, where her father married her to Geoffrey, Count of Anjou. All the magnates of England and Normandy were required to declare fealty to Matilda as Henry's heir, but when Henry I died in 1135, Stephen rushed to England and had himself crowned before either Theobald or Matilda could react. The Norman barons accepted Stephen as Duke of Normandy, and Theobald acquiesced to his brother's usurpation.[2]

Matilda, though, was not reconciled to losing the throne, and secured the support of the Scottish king, David, who was her maternal uncle. In 1138 she also secured the support of her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester the Earl of Gloucester, an illegitimate son of Henry I.[2] Most of the reign of King Stephen was dominated by the efforts of Matilda and later her son, Henry of Anjou to oust Stephen from the throne. The height of the civil war was from 1142 to 1148, but it began in 1138 when Robert of Gloucester declared for Matilda, after previously supporting Stephen. Traditionally, historians have referred to the period of civil war as "The Anarchy", but recent scholarship has rejected the extreme view of the time period as lawless; most historians see the reign as disordered but not highly so, and Stephen as weak but not useless.[3]

Early life

Chesney was the son of Roger de Chesney and Alice de Langetot.[4] The elder Chesney came from near Quesney-Guesnon in the Calvados region of Normandy, and held lands in England from Robert d'Oilly at the time of the Domesday Survey in 1087.[5] Alice was the daughter of Ralph de Langetot,[6] who held lands of Walter Giffard at the time of Domesday.[7] William's brother Robert de Chesney later became Bishop of Lincoln.[8] His other siblings were Reginald, who later became abbot of Evesham Abbey,[9] Hugh, Ralph, Hawise, Beatrice, Isabel,[5] and Roger.[10] Chesney was the uncle of Gilbert Foliot who became successively abbot of Gloucester Abbey, Bishop of Hereford and Bishop of London.[11] It is likely that it was one of William's sisters that married Gilbert's father, although there is no sure evidence of this.[12] Chesney also mentioned as relatives the brothers Alexander de Chesney and Ralph de Chesney, but the exact relationship is unknown.[13] Chesney needs to be distinguished from another William de Chesney,[4] who held the office of Sheriff of Norfolk between 1146 and 1153.[14][lower-alpha 2]

Career

William and his brother Roger de Chesney were leading supporters of King Stephen in 1141, and were both leaders in Stephen's army that gathered at Winchester. In 1143, William de Chesney was given control of the town and royal castle at Oxford. He also held the town and castle of Deddington,[10] which he had acquired at least by 1157, and possibly earlier. Although he did not begin the fortifications at Deddington Castle, it is likely that he began the first stone defences at the site.[16] Deddington was Chesney's most important holding in Oxfordshire, and the basis of his power in the county.[17]

Before he controlled Deddington, Chesney temporarily administered the lands of Robert d'Oilly, who had previously held Oxford Castle but had defected to the side of the Empress Matilda in 1141 and died a year later. D'Oilly's heir took refuge with Matilda when Stephen overran his lands two weeks after his father's death, leading to Chesney's control of the d'Oilly lands.[10] Some historians have seen this holding of the lands as Stephen giving Chesney the d'Oilly barony, but the only evidence for this is that Chesney eventually owned a manor previously belonging to d'Oilly which does not necessarily mean that he received the whole barony. It is far more likely that Stephen gave Chesney parts of the lands of William fitzOsbern, which had reverted to the king in 1075. Most of the known lands of fitzOsbern are known to have been owned by Chesney or by tenants who held the lands from him.[17]

Historians are divided in their views as to whether Chesney held the office of Sheriff of Oxfordshire.[9][18] Whatever the exact office that Chesney held in Oxfordshire, the townsmen of Oxford referred to him as their "alderman" before such honorifics were in common use.[9]

In 1145, Chesney was forced to ask Stephen for help in fending off the approach of Philip, a younger son of Robert, Earl of Gloucester, who was threatening Chesney's control of Oxford.[19] During the period 1142–1148 Chesney forced Gloucester Abbey, then under the abbacy of his nephew Gilbert Foliot, to pay him sums of money.[20] Foliot, in one of his surviving letters, reprimanded his uncle for his behaviour, asking him "Which of God's poor around you have you not harmed?"[21] In 1147, Chesney granted the island of Medley to Osney Abbey in the name of his father and brother Roger, as well as King Stephen, Queen Matilda and their son Eustace.[22] After 1148, Chesney apparently began to hedge his bets as he appears in the company of Roger of Hereford, the Earl of Hereford, who was a firm supporter of Matilda's and her son Henry's cause.[23]

Chesney served again as the leader of Stephen's army at Wallingford Castle in 1153 and in August he was defeated by Henry of Anjou.[24] The subsequent peace settlement, the Treaty of Wallingford, gave Henry the English throne after Stephen's death. A part of the treaty awarded control of Oxford Castle to Roger de Bussy.[25] Although Chesney had lost control of the castle, none of his lands were confiscated.[26] Early in 1154, Chesney was with Henry, as he was a witness on two charters of Henry's.[27] After Henry's ascension to the throne, Chesney came to terms with the new king,[4] and received confirmation of his lands from the king by 1157.[28] He spent time in Normandy with Henry from 1159 through to 1161.[4] He continued to receive favours from the king, such as exemption for payment of danegeld on his manor of Deddington in 1156.[29]

Chesney married Margaret de Lucy,[4] who was probably a relative of Richard de Lucy, another of Stephen's main supporters.[30] He died sometime between 1172 and 1176.[31] Chesney's heir was his niece Matilda, whom King Henry II married to Henry fitzGerold, a royal chamberlain.[26]

Notes

- Henry I had more than 20 illegitimate children.[1]

- This William de Chesney was the son of Robert fitzWalter and Sybil de Chesney and was the lord of Blythburgh in Suffolk.[4] Sybil was the daughter of Ralph de Chesney,[13] who was the son of Roger de Chesney and Alice de Langetot, making this William the great-nephew of William de Chesney of Oxford.[15]

Citations

- Hollister Henry I p. 41

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 71–73

- Huscroft Ruling England pp. 71–76

- Keats-Rohan Domesday Descendants p. 370

- Keats-Rohan Domesday People p. 402

- Keats-Rohan Domesday Descendants p. 541

- Keats-Rohan Domesday People p. 333

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen p. 239 footnote 19

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen pp. 326–327

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen p. 205

- King "Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign" Transactions of the Royal Historical Society p. 153

- Salter "Appendix I" Eynsham Cartulary p. 412

- Keats-Rohan Domesday Descendants p. 369

- Green English Sheriffs p. 77

- Keats-Rohan Domesday Descendants p. 368

- Ivens "Deddington Castle" Oxoniensia p. 111

- Amt Accession of Henry II pp. 52–53

- Green English Sheriffs pp. 69–70

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen p. 217

- Callahan "Ecclesiastical Reparations" Albion p. 316

- Quoted in Amt Accession of Henry II p. 52

- Salter "Appendix I" Eynsham Cartulary p. 415

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen p. 239

- Crouch Reign of King Stephen p. 269

- Amt Accession of Henry II pp. 56–57

- Amt Accession of Henry II pp. 60–61

- White "End of Stephen's Reign" History p. 14

- Amt "Meaning of Waste" Economic History Review p. 244

- Amt Accession of Henry II p. 137

- Amt Accession of Henry II p. 51

- Ivens "Deddington Castle" Oxoniensia p. 114

References

- Amt, Emilie (1993). The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored 1149–1159. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-348-8.

- Amt, Emilie M. (May 1991). "The Meaning of Waste in the Early Pipe Rolls of Henry II". Economic History Review. XLIV (2): 240–248. doi:10.2307/2598295. JSTOR 2598295.

- Callahan Jr., Thomas (Winter 1978). "Ecclesiastical Reparations and the Soldiers of 'The Anarchy'". Albion. 10 (4): 300–318. doi:10.2307/4048162. JSTOR 4048162.

- Crouch, David (2000). The Reign of King Stephen: 1135–1154. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-22657-0.

- Green, Judith A. (1990). English Sheriffs to 1154. Public Record Office Handbooks Number 24. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-440236-1.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2001). Frost, Amanda Clark (ed.). Henry I. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08858-2.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Ivens, R. J. (1984). "Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honour of Odo of Bayeux" (pdf). Oxoniensia. 49: 101–119. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (1999). Domesday Descendants: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166: Pipe Rolls to Cartae Baronum. Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-863-3.

- Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. (1999). Domesday People: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166: Domesday Book. Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-722-X.

- King, Edmund (1984). "The Anarchy of King Stephen's Reign". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Fifth Series. 34: 133–153. doi:10.2307/3679129. JSTOR 3679129.

- Salter, H. E. (1907). "Appendix I: The Family of Chesney". The Eynsham Cartulary. 1. Oxford, UK: Claredon Press. pp. 411–423.

- White, Graeme J. (January 1990). "The End of Stephen's Reign". History. 75 (243): 3–22. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1990.tb01507.x.