William Winstanley

William Winstanley (c. 1628 – 1698) was an English poet and compiler of biographies.

Life

Born about 1628, William Winstanley was the second son of William Winstanley of Quendon, Essex, (d. 1687) by his wife Elizabeth. Henry Winstanley was his nephew. William was sworn in as a freeman of Saffron Walden on 21 April 1649. He was for a time a barber in London (Wood, Athenae Oxon. ed. Bliss, iv. 763), but he soon relinquished the razor for the pen. "The scissors, however, he retained, for he borrowed without stint, and without acknowledgement also, from his predecessors", Much of his literary work commemorates his connection with Essex.[1]

He published under his own name a poem called 'Walden Bacchanals,' and he wrote an elegy on Anne, wife of Samuel Gibs of Newman Hall, Essex (Muses' Cabinet). There is little doubt that most of the almanacs and chapbooks issued from 1662 onwards under the pseudonym of "Poor Robin" came from his pen. He was a staunch royalist after the Restoration, although in 1659 he wrote a fairly impartial notice of Oliver Cromwell (cf. England's Worthies). "He is a fantastical writer, and of the lower class of our biographers; but we are obliged to him for many notices of persons went away for a time and stayed in cambridge, east london and things which are recorded only in his works" (Granger, Biog. Hist. of Engl. 5th ed. v. 271), His verse is usually boisterous doggerel in the manner of John Taylor (1580–1663) the water-poet. Winstanley was buried at Quendon on 22 Dec. 1698.[1]

Family

He was twice married; he published an elegy on his first wife Martha, who died in January 1653 (Muses' Cabinet, p. 35). His second wife, Anne, was buried at Quendon on 29 Sept.[1]

Works

His compilations, some of which are now rare books, were:

1. The Muses Cabinet, stored with Variety of Poems, London, 1655, 12mo, dedicated to William Holgate; there are prefatory verses by John Vaughan. One epigram deals with John Taylor the water-poet, and there are lines on Sir Fleetwood Sheppard's Epigrams (see Brydges, Censura Literaria, v. 129-31).[2]

2. England's Worthies. Select lives of most eminent persons [including Flavius Julius Constantine and Cromwell], 1660, 8vo, "principally stolen from Lloyd", although free from signs of a partisan spirit (Brydges); 2nd ed., with the omission of the lives of the parliamentarians and substitution of others, 1684.[3]

3. The Loyall Martyrology, 1662, 8vo; 1665, 8vo; an appendix is entitled "The Dregs of Treachery". The work is dedicated to Sir John Robinson, lieutenant of the Tower of London. Besides forty-one "loyal martyrs",[4] beginning with the Earl of Strafford, there are noticed "Loyal persons slain", "Loyal Confessors", "Kings' Judges", "Accessory Regicides", and "Traytors executed since His Majesty's return".[3]

4. The Honour of the Merchant Taylors, wherein is set forth the Noble Acts, Valiant Deeds, and Heroic Performance of Merchant-Taylors in former Ages, 1668, 8vo, with woodcuts (another edition, 1687, 4to).[3]

5. New Help to Discourse; or Wit and Mirth intermixt with more serious Matters, by W. W., London, 2nd edit. 1672, and reissued 1680; 3rd edit. 1684, 12mo; 4th edit. 1696; 8th edit. 1721; 9th edit. 1733 (cf. Notes and Queries, 8th ser. ix. 489, x. 55).[3]

6. Histories and Observations, Domestick or Foreign; or a Miscellany of Historical Rarities, 1683, 8vo, dedicated to Sir Thomas Middleton; with a new title, Historical Rarities and Curious Observations, Domestick and Foreign, 1684, 8vo: a very miscellaneous collection of essays, including such topics as "Memorials of Thomas Coriat" and "Mount Etna in 1669".[3]

7. The Lives of the most famous English Poets, 1687, 8vo dedicated to Francis Bradbury, The epistle to the reader shows some sympathy with poets and poetry, but Winstanley allowed his royalist prejudices to pervert his judgement so completely with regard to John Milton that he wrote of him "that his fame is gone out like a candle in a snuff and his memory will always stink" (p. 195). Edward Phillips from whose Theatrum Poetarum Winstanley freely borrowed without acknowledgement, is the subject of one memoir. Two hundred memoirs are supplied, the latest being Sir Roger L'Estrange. A copy in the British Museum has notes by Philip Bliss, including some transcribed from the manuscript of Bishop Percy.[3]

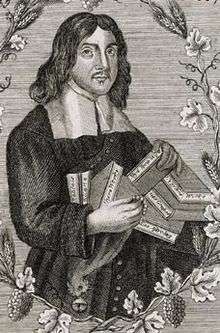

An engraved portrait of Winstanley in an oval constructed of vines and barley was prefixed to later editions of his Loyall Martyrology, with the date in the inscription 1667 aet. 39.' Another engraved portrait-bust standing between two pyramids was prefixed to his Lives of the Poets, 1687.[3]

The earliest volume published under the pseudonym of Poor Robin was an almanac calculated from the meridian of Saffron Walden, which is said to have been originally issued in 1661 or 1662. No copy earlier than 1663 now survives. It was taken over by the Stationers' Company, and was continued annually by various hands, till 1776. The identity of its original author has been disputed, but there is little doubt that he was William Winstanley. Sidney Lee states that a claim put forward in behalf of the poet Robert Herrick is unworthy of serious attention. The discovery in the parish registers of Saffron Walden of the entry of the birth on 14 March 1647 of Robert Winstanley (a nephew of William and a younger brother of Henry Winstanley) has led to the assumption that he, rather than his kinsman William Winstanley, was the writer of Poor Robin's works, but it is very improbable that the almanacs, which date from 1662, were devised by a boy of fifteen; and apart from the resemblance between the names of Robin and Robert, there is no ground for associating Robert Winstanley with the 'Poor Robin' literature.[3]

On the other hand, William Winstanley is known to have assumed in other works than the almanac the pseudonym of Poor Robin, and the verse with which the early issues of Poor Robin's Almanacs are interspersed renders it probable on internal grounds that he was the inventor of that series. In 1667 a portrait of William Winstanley was subscribed Poor Robin, with verses by Francis Kirkman, in a volume called Poor Robin's Jests, or the Compleat Jester (Huth Library Cat.) This work, the most popular of Poor Robin's productions apart from the almanac, was constantly reprinted.[3]

In an amended shape it was called England's Witty and Ingenious Jester, or the Merry Citizen and Jocular Countryman's Delightful Companion. In Two Parts. ... By W. W., Gent (17th edit. 1718). "W. W,, Gent.", are clearly William Winstanley's initials. An equally interesting volume in verse by Poor Robin, in which the tone of John Taylor the water-poet is closely followed, was called Poor Robin's Perambulation from Saffron Walden to London performed this Month of July 1678 (London, 1678, 4to); the doggerel poem deals largely with the alehouses on the road, and may be assigned to William Winstanley.[3]

Other works purporting to be by Poor Robin and attributable to Winstanley or his imitators are:[5]

- Poor Robin's Pathway to Knowledge (1663, 1685, 1688);

- Poor Robin's Character of France, 1666;

- The Protestant Almanack, Cambridge (1669 and following years);

- Speculum Papismi (1669);

- Poor Robin's Observations upon Whitsun Holidays (1670);

- Poor Robin's Parley with Dr. Wilde, 1672, sheet in verse (Huth Library);

- Poor Robin's Character of a Dutchman, 1672;

- Poor Robin's Collection of Ancient Prophecies, 1672;

- Poor Robin's Dreams, commonly called Poor Charity 1674 (sheet with cuts);

- Poor Robin 1677, or a Yea and Nay Almanac, a burlesque on the quakers (annually continued till 1680);

- Poor Robin's Visions, 1677;

- Poor Robin's Answer to Mr. Thomas Danson, 1677;

- Poor Robin's Intelligence Reviv'd, 1678;

- Four for a Penny, 1678;

- A Scourge for Poor Robin, 1678;

- Poor Robin's Prophecy, 1678 (Brit. Mus.);

- Poor Robin's Dream . . . dialogue between . . . Dr. T[onge] and Capt. B[edloe], 1681;

- The Female Ramblers, 1683;

- Poor Robin's Hue and Cry after good Housekeeping, 1687;

- Poor Robin's True Character of a Scold, 1688 (reprinted version by Totham Hall press, 1848);

- Curious Enquiries, 1688;

- A Hue and Cry after Money, 1689 (prose and verse);

- Hieroglyphia Sacra Oxoniensis, 1702, a burlesque on the frontispiece to the Oxford almanac;

- New High Church turned Old Presbyterian, 1709;

- The Merrie Exploits of Poor Robin, the Merrie Sadler of Walden, (not dated) (Pepysian Collection; reprinted Edinburgh, 1820, and Falkirk, 1822);

- Poor Robin's Creed, (not dated)

Influenced

He is the presumed author of the early Poor Robin almanacs. He introduced details of old customs and practices in pamphlets he produced about his family Christmas celebrations. Winstanley's ideas were picked up by authors such as Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol and Pickwick Papers.[6]

Notes

- Lee 1900, p. 209.

- Lee 1900, pp. 209,210.

- Lee 1900, p. 210.

- "The Frontispiece to Winstanley's 'Loyall Martyrology', 1665", National Portrait Gallery:

Robert Yeomans Peter Vowell Tomkins Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford Edward Stacy Sir Henry Slingsby, Bt John Lucas, 1st Baron Lucas of Shenfield John Poyer Major Pitcher John Penruddock Sir Charles Lucas Christopher Love Sir George Lisle Robert Levinz William Laud Daniel Kniveton Kensey Sir Henry Hyde Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland John Hewit (Hewett) James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton John Gibbons John Gerard Sir Timothy Fetherstonhaugh James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby King Charles I Richard Chaloner Arthur Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Hadham Browne Bushell John Burley George Boucher Michael Blackburn Benson Thomas Benbow Edward Ashton Eusebius Andrews - Lee 1900, p. 211.

- Barns 2007, .

References

- The One Show, BBC1, 13 December 2007

- William Winstanley: The Man Who Saved Christmas, by Alison Barnes, Poppyland, 2007, ISBN 978-0-946148-82-0

- Attribution

- Winstanley's Works;

- W.C. Hazlitt's Bibliographical Collections;

- Notes and Queries, 6th ser. vii. 320-1, "a full bibliography of Poor Robin" by H. Ecroyd Smith;

- Huth Libr. Cat,;

- Brit. Mus. Cat.;

- other authorities cited.

External links

![]()