William Kirkcaldy of Grange

Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange (c. 1520 –3 August 1573) was a Scottish politician and soldier who fought for the Scottish Reformation but ended his career holding Edinburgh castle on behalf of Mary, Queen of Scots and was hanged at the conclusion of a long siege.

Family

Grange held lands at Hallyards Castle in Fife. William's father, James Kirkcaldy of Grange (died 1556), was lord high treasurer of Scotland from 1537 to 1543 and a determined opponent of Cardinal Beaton, for whose murder in 1546 William and James were partly responsible.[1]

William was married to Margaret Learmonth, sister of Sir Patrick Learmonth of Dairsie and Provost of St Andrews. A few days before Grange's execution in August 1573, Ninian Cockburn reported a rumour that he had a child with a young woman and had written a letter in code to her.[2]

War with England, service with France, and the Reformation

William, with other courtiers, had been a witness to the instrument made at Falkland Palace at the deathbed of James V of Scotland in 1542 which Cardinal Beaton used to attempt to claim the Regency of Scotland.[3] However, William participated in the Cardinal's murder in May 1546, and when St Andrews Castle surrendered to the French in July the following year he was sent as a prisoner to Normandy, whence he escaped in 1550.[1]

He was then employed in France as a secret agent by the advisers of Edward VI, being known in the cyphers as Corax; and later he served in the French army, where he gained a lasting reputation for skill and bravery.[1] Kirkcaldy was in London in December 1553, discussing border issues with the French ambassador, Antoine de Noailles.[4]

The sentence passed on Kirkcaldy for his share in Beaton's murder was removed in 1556. Returning to Scotland in 1557 he became prominent by killing Ralph Eure the brother of the Governor of Berwick upon Tweed in a duel. As a Protestant he was one of the leaders of the Lords of the Congregation in their struggle with the Regent of Scotland, Mary of Guise.[1] Kirkcaldy fought the French troops in Fife and they destroyed his house at Halyards. In January 1560 he took down part of Tullibody bridge to delay the return to Stirling of French troops commanded by Henri Cleutin.

Kirkcaldy opposed Queen Mary's marriage with Lord Darnley, and was associated with her half-brother the Earl of Moray at the time of the Chaseabout Raid. For this defiance, he was forced for a short time to seek refuge in England. Returning to Scotland, he was an accessory to the murder of Rizzio, but he had no share in Darnley's assassination.[1]

Kirkcaldy was opposed to Mary's marriage with Bothwell and regarded the proceedings in the Scottish Parliament with dismay. He wrote to the Earl of Bedford, an English diplomat, that Mary did not care if she lost France, England and Scotland for Bothwell's sake, and Mary had said;

she sall go with him to the warldes ende in ane white peticote or she leve him.[5]

Elizabeth however disapproved of Kirkcaldy's opinions of a fellow queen as if she were "worse than any common woman."[6] Yet Kirkcaldy was one of the lords who banded themselves together to rescue Mary after her marriage with Bothwell. After the fight at Carberry Hill the queen surrendered herself to Kirkcaldy.[1] Bothwell escaped and Kirkcaldy sailed to Shetland as Lord High Admiral of Scotland in pursuit. He was determined to capture Bothwell and declared to the Earl of Bedford, Governor of Berwick:

Albeit I be na gud seeman, I promes unto your lordschip, gyf I may anes enconter with hym eyther be see or land, he sall eyther carre me with hym, or ellis I sall bryng hym dead or quik to Edinbrucht.[7]

However, they did not meet, his ship, the Lion, ran aground north of Bressay.[8]

After Mary escaped from imprisonment at Lochleven Castle, his military command was mainly responsible for her defeat at the Battle of Langside. He seems, however, to have believed that a peaceful settlement with Mary was possible, and coming under the influence of William Maitland of Lethington, whom in September 1569 he released by a stratagem from his confinement in Edinburgh, he was soon vehemently suspected by his fellows.[9]

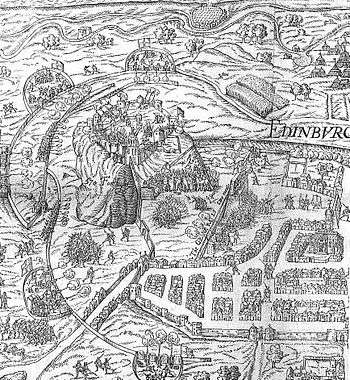

The "Lang Siege"

After the murder of Regent Moray in January 1570, William Kirkaldy of Grange ranged himself definitely among the friends of the imprisoned queen. Defying Regent Lennox, Grange began to strengthen the fortifications of Edinburgh castle and town, of which he was captain and Provost, and now held for Mary. He forcibly released one of his supporters from imprisonment in Edinburgh's tolbooth, a step which led to an altercation with his former friend John Knox, who called him a murderer and throat-cutter.[10] He arrested some leading burgesses on 29 April 1571. The King's party established their headquarters in Leith. The subsequent period has become known as the "Wars between Leith and Edinburgh." In May Kirkcaldy built fortifications in the town, on the Royal Mile and on St Giles Kirk.[11] In October 1571 the town council established itself in Leith, and Grange's men fortified Edinburgh by blocking the ends of streets and closes and burning houses on the outskirts of the city, such as Potterrow. The "lang siege" of Edinburgh castle began in mid-October, when Regent Mar brought artillery from Dumbarton and Stirling Castle.[12]

Grange received supplies and money from France, England, and the Spanish Netherlands where George Seton, 7th Lord Seton negotiated with the Duke of Alva. John Chisholm, Master of the Scottish Artillery, obtained money and arms from the exiled Bishop of Glasgow and Charles IX of France.[13] He sailed from Dieppe in June 1571 but was captured at North Queensferry.[14] Grange established a mint in the castle to coin silver and raised loans by pawning jewellery belonging to Mary, Queen of Scots.[15] On 27 January 1573, William's brother, James Kirkcaldy arrived at Blackness Castle with arms and money from France, but the castle was besieged by Regent Morton, and James Kirkcaldy was captured.[16] Early in 1573, Kirkcaldy refused to come to an agreement with Regent Morton because the terms of peace set out by the "Pacification of Perth" did not include a section of his friends.[10]

After this, English troops and artillery arrived to help Regent Morton and the King's party, and on 28 May 1573 the castle surrendered. The English commander Sir William Drury took Grange to his lodgings at Robert Gourlay's House[17] and then to Leith. During this time Master Archibald Douglas negotiated with Grange and Drury over the jewels belonging to Mary, Queen of Scots.[18] After a week Grange was handed over to Regent Morton and imprisoned in Holyroodhouse.[19]

Ninian Cockburn said that Grange had a child with a young woman and wrote her a love letter from his imprisonment.[20] Strenuous efforts were made to save Kirkcaldy from the vengeance of his enemies, but they were unavailing; Knox had prophesied that he would be hanged, and he was hanged on 3 August 1573.[10][21]

A year later, one of Grange's letters came to light, which mentioned the jewels Mary, Queen of Scots had left behind in Scotland, and that Drury had taken some as a pledge for a loan of £600.[22]

Posthumous rehabilitation

On 15 July 1581, James VI restored his lands to his heirs, giving a long recitation of Kirkcaldy's service, mentioning a single combat in 1557 while Scotland was at war with England,[23] his support of the Scottish Reformation, and his conduct at Carberry Hill and pursuit of Bothwell;

Schir Williame Kirkcaldie of Grange, quhen weiris stude betuix this realme and Ingland, did sic vailyeand and acceptable service at mony common jeopardis in thai weiris, and als did sa vailyeantlie and manfullie in ane singular combat according to the law of armeis that it meritis perpetuall commendatioun, lyke als alsua he wes ane of the maist notabill instrumentis usit be almichtie God amangis the nobilitie and gentilmen of this realme in suppressing the idolatrus religioun, ...

als as ane of the maist bent to the revealing of the odious murthour of his hienes derrest fader and offerit his body to ony of honest degre that would tak the defence of the erle of Bothwell, and to have had revenge followit him upoune the seyis to Zetland, quhair Schir Williame wes than schipbrokkin in greit hasert, ...

Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange, when wars stood between this realm and England, did such valiant and acceptable service at many battles in those wars, and also did so valiantly and manfully in a single combat according to the Laws of Arms that it merits perpetual commendation, and likewise he was one of the most notable instruments used by Almighty God amongst the nobility and gentlemen of this realm in suppressing idolatrous religion, ... and one of the most keen to reveal the odious murder of the king's father and offered his body to any of honest degree that would take the defence of the Earl of Bothwell (at Carberry), and to have revenge followed him by sea to Shetland, where Sir William in great danger shipwrecked ...[24]

William's heir was his nephew, also William Kirkcaldy, son of his brother Master James Kirkcaldy.[25]

Further reading

- Louis A. Barbé, Kirkcaldy of Grange, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, Oct 1897, ("Famous Scots Series")

- Lynch, Michael, Edinburgh and the Reformation, John Donald, (2nd ed. 2003). ISBN 1904607055

- Potter, Harry, Edinburgh Under Siege: 1571–1573, Tempus, (2003). ISBN 0-7524-2332-0

References

- Chisholm 1911, p. 830.

- Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. iv, (1905), 601

- Historical Manuscripts Commission 11th Report Part 6, Manuscripts of the Duke of Hamilton (London, 1887), 219-220.

- Abbé de Vertot, Ambassades de Messieurs de Noailles en Angleterre, vol.2 (Leyden, 1763), 236.

- V. Smith, 'Perspectives on Female Monarchy', in J. Daybell & S. Norrhem, Gender and Political Culture in Early Modern Europe (Abingdon, 2017), 153: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 2 (1900), 322.

- V. Smith, 'Perspectives on Female Monarchy', in J. Daybell & S. Norrhem, Gender and Political Culture in Early Modern Europe (Abingdon, 2017), 153.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland Papers, vol. 2 (1900), 378.

- Reid, David ed., Hume of Godscroft's History of the House of Angus, vol. 1, STS (2005), 171: Strickland, Agnes, ed., Letters of Mary Queen of Scots, vol.1 (1842), pp. 244-248

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 830–831.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 831.

- Lynch, Michael, Edinburgh and the Reformation, John Donald, (2003), pp.125-131.

- Lynch, Michael, Edinburgh and the Reformation, John Donald, (2003), p.137.

- Correspondance Diplomatique De Bertrand De Salignac De La Mothe Fenelon, vol.4, Paris (1840), pp.203-4

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol.3 (1903), pp.478-480, 485-7, 529, 532-3, 535, 620-1, 623-4, 636

- M. Lynch, Edinburgh and the Reformation, (Edinburgh, 1981), 138-9, 145, 147

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 4 (1905), pp. 477, 478, 482, 483-4, 486-7

- Daniel Wilson, Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Time, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1891), p. 226.

- J. Robertson ed., Inventaires de la Royne Descosse, (Edinburgh, 1863), pp. cl-i

- H. Potter, Edinburgh under Siege, 1571-1573, (Stroud, 2003), 141-6

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-1574, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 601.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland: 1571-1574, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 602.

- William Boyd, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 36.

- James Melville of Halhill mentions this combat, while the armies of Scotland and England faced each other, and calls the opponent "the brother of the Earl of Rivers," Memoirs, (1929), 225: Humfrey, Barwick, A breefe discourse, concerning the force and effect of all manuall weapons of fire, London (1592), p.21, describes how Kirkcaldy ran Euers or Ewrie through with a spear despite his armour: Holinshed, Chronicles: Scotland, vol.5 (1808), p.585, has "Ralph Eure brother to Lord Eure."

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 8 (HMSO, 1982), pp. 66-67 no. 397 abbreviated.

- Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 8, HMSO, (1982), 378, no. 2197.