William John Warburton Hamilton

William John Warburton Hamilton (April 1825 – 6 December 1883), who generally signed as J. W. Hamilton, was an administrator, explorer, and politician in New Zealand.

Early life

Hamilton was born in 1825 at Little Chart, Kent, England. His father was Rev John Vesey Hamilton, and Richard Vesey Hamilton was his younger brother. He was educated in England, Paris, Brussels, and at Harrow School. He emigrated aged 18 on the Bangalore with Sydney in Australia as his destination, but he met Robert FitzRoy on the journey and became his private secretary; FitzRoy was travelling to take up the role of Governor of New Zealand.[1]

Early time in New Zealand

Hamilton served for FitzRoy until the latter was recalled, and then worked under the next governor, George Grey. Hamilton returned to England in 1846. He returned on HMS Acheron in 1848 as a survey officer.[1] From inland explorations, geographic features were named for him, including Hamilton Plains (now known as Hanmer Plain) on the Waiau River, and the nearby Mount Hamilton.[2] In 1849, he attempted the first known ascent of Mount Tapuaenuku in the Kaikoura Ranges. He was with Edward John Eyre, Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster, and seven Māori. They came within a short distance of the summit but were forced to turn back.[3]

In 1850, Governor Grey appointed Hamilton resident magistrate for Wanganui, which was a significant responsibility for a person aged 25.[4]

Life in Canterbury

Hamilton held the post in Wanganui for about half a year only before he took on another role at Port Cooper (now known as Lyttelton).[5] At Lyttelton, he was appointed collector of customs for Canterbury in August 1853.[1]

On 6 November 1855, Hamilton married Frances Townsend, daughter of James Townsend of Ferrymead.[6] She was the eldest sister of the artist Mary Townsend.[7]

In the first elections for the Canterbury Provincial Council on 31 August 1853, five people contested the three available positions in the Town of Lyttelton electorate. Hamilton came a close second, and was thus returned; the other successful candidates were Isaac Cookson and Christopher Edward Dampier (the solicitor of the Canterbury Association.[8] In November 1853, he was appointed onto the first Executive Council (comparable to a cabinet) as Provincial Auditor under Henry Tancred.[9] During a day of low attendance in October 1854, Richard Packer secured a suspension of the council's standing orders, which allowed him to have the first two readings of a bill to enlarge the council's membership by 12 additional members passed. Whilst there was justification for such a measure due to the long session lengths, the Executive Council consisting of Tancred, Henry Godfrey Gouland, Charles Simeon, and Hamilton regarded the matter as a vote of no confidence and resigned.[10][11][12] He was a member of Tancred's second Executive Council (July 1855 – February 1857) and on the Executive led by Packer (February – June 1857).[4][13] He retired at the end of his term as provincial councillor in July 1857 and did not seek re-election.[4]

He was appointed resident magistrate of Christchurch in February 1856. When he left the customs service, he became receiver of land revenue. He retired in 1874.[4] For some time, he was manager of the Union Bank in Lyttelton. In 1861, Charles Bowen sold his interest in the Lyttelton Times to William Reeves and Hamilton. He was a governor of Christ's College, and was on the board of Canterbury College (1875–1883).[4]

As a resident magistrate, he was widely respected for his fair dealings.[4] His contribution to the provincial government was regarded as valuable, especially his understanding of finances. As a government official, he was perceived by William Ellison Burke, the avid recorder of Canterbury personalities in the 1850s and 1860s, as "crotchety official – a wearisome magistrate". Burke wrote:[14]

Mr. H. was notoriously the most perfect embodiment of red tape who ever held office in Canterbury. His memos and questions upon documents were masterpieces and calculated to try the patience of the most saintly. As a magistrate he was a drawler and doubter and questioner who ever sat on the Bench of Christchurch. He had a supercilious style when he chose to be offensive and was very inquisitive.

Hamilton died on 6 December 1883 at his home in Latimer Square.[15][16] Colleagues from the Lyttelton Times were pall bearers and carried the coffin from his home to Barbadoes Street Cemetery.[15] His wife died in 1889.[14]

Notes

- Scholefield 1940, p. 349.

- Reed 2010, p. 154.

- Stephens, Joy. "Marlborough's Sacred Mountain". The Prow. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Scholefield 1940, p. 350.

- "Wellington". Lyttelton Times. I (20). 24 May 1851. p. 6. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Married". Lyttelton Times. V (315). 7 November 1855. p. 5. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Local and General". The Star (506). 3 January 1870. p. 2. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Lyttelton Election". Lyttelton Times. I (20). 24 May 1851. p. 6. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "Page 6 Advertisements Column 1". Lyttelton Times. III (150). 19 November 1853. p. 6. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Hight 1957, pp. 220–221.

- "Page 4 Advertisements Column 1". Lyttelton Times. IV (209). 1 November 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- "The Lyttelton Time". Lyttelton Times. IV (209). 1 November 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Scholefield 1950, pp. 190–191.

- Greenaway, Richard L. N. (June 2007). "Barbadoes Street Cemetery Tour" (PDF). Christchurch City Council. pp. 49–51. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- McLintock 1966.

- "Obituary". The Press. XXXIX (5685). 7 December 1883. p. 3. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

References

- Hight, James; Straubel, C. R. (1957). A History of Canterbury. Volume I : to 1854. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLintock, A. H., ed. (22 April 2009) [originally published in 1966]. "Hamilton, William John Warburton". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- Reed, A. W. (2010). Peter Dowling (ed.). Place Names of New Zealand. Rosedale, North Shore: Raupo. ISBN 9780143204107.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

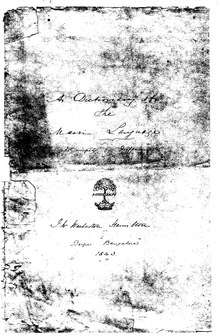

- Scholefield, Guy, ed. (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand Biography : A–L (PDF). I. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 21 September 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First published in 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)