William Hoskins (inventor)

William Hoskins (1862–1934)[1][2][3] was an American inventor, chemist, electrical engineer, and entrepreneur in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most active in Chicago, Illinois. He became the co-inventor in 1897 of modern billiard chalk with professional carom billiards player William A. Spinks.[4][5] He is, however, best known for the invention of the electric heating coil – the basis for numerous ubiquitous household and industrial appliances, including electric stoves, space heaters, and toasters – and the invention of the first electric toaster.[6][7]

William Hoskins | |

|---|---|

William Hoskins, with daughter Florence and wife Ada, c. 1885–1890 | |

| Born | 1862 |

| Died | 1934 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Inventor |

Notable work | Billiard chalk, electric heating coil |

Career

Early life

William Hoskins was born in 1862 to parents John and Mary Ann Hoskins, in Chicago.[3] Hoskins would complete just two of three years of Chicago High School;[1][3] despite having an interest in chemistry, he would gain no formal education in chemistry throughout his early years.[1] Hoskins, however, received "private instruction" in the field,[3] before joining (at age thirteen), the Illinois State Microscopical Society. Four years later, at 17, the society elected him secretary.[2]

After leaving high school in 1880 at age 17, Hoskins prepared chemical analysis samples[1] for Chicago-based consulting and analytical chemist Guy A. Mariner in the latter's commercial laboratory,[2] starting in February.[3] Beginning in 1880, Mariner was one of only three completely commercial chemists in Chicago.[1] Five years after joining the laboratory, Hoskins became Mariner's partner; the firm was renamed Mariner and Hoskins.[1][2][3] Shortly before becoming the partner, Hoskins married Mariner's daughter,[1] Ada Mae,[lower-alpha 1] on December 18, 1883.[3] In 1890, Hoskins became sole proprietor of the laboratory.[2][3] The couple subsequently had four children: Minna, Edward, William, and Florence.[3]

Later career

In 1897, Hoskins began working with William A. Spinks before becoming a partner in William A. Spinks & Co.[2][3] In the early 1900s, Hoskins would also become the director of Hoskins Manufacturing Co., based in Detroit, creating electric heating appliances and pyrometers.[2][3] He was made a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS),[3] and was also a charter member of the Chicago section of the American Chemical Society (ACS),[1][8] of which he was the chairman in 1897,[8] later becoming the national ACS's vice-president,.[3] Hoskins Manufacturing eventually become Hoskins Process Development Co., of which he was the president.[2] Hoskins became a recognized scientific expert witness in lawsuits,[1] took out 37 US patents,[1] and in Hoskins's lab, Albert L. Marsh developed nichrome under supervision of Hoskins.[1][9] Hoskins's own innovations include a superior billiard chalk, materials used to construct race tracks (including the Washington Park Race Tracks in Chicago), safety paper for bank checks, a method for destroying weeds, and a gasoline blowtorch.[2][10]

Inventions

Electric heating coil

William Hoskins is credited with invention of the electric heating coil. In the early 1900s, having worked on a form of nichrome known as chromel, working with Marsh over the alloy, he deduced that it could be used as a heating element.[10] The heating coil was created using nichrome, and was later used in early versions of the toaster, and the electric kettle.[11] The heating coil was one of the first projects for Hoskins Manufacturing Co.; Hoskins had considered manufacturing toasters, but later abandoned those plans, and focused on the coil itself.[12]

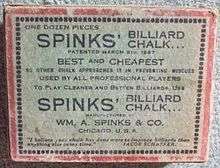

Billiard chalk

In the late 19th century,[13] actual chalk (generally calcium carbonate, also known as calcite or carbonate of lime) was often used in cue sports on the leather tips of cue sticks to better grip the cue ball, but players experimented with other powdery, abrasive substances, since chalk itself was too abrasive, and over time damaged the game equipment.[14][15] In 1892,[15] the aforementioned straight rail billiards pro William Spinks was particularly impressed by a piece of natural chalk-like substance obtained in France, and presented it to Hoskins for analysis. Hoskins, having encountered such material before, was able to determine that it was volcanic ash (pumice), probably from Mount Etna, Sicily. The two of them experimented with different formulations to achieve the cue ball "action" that Spinks sought.[4]

They settled on a mixture of Illinois-sourced[4] silica with small amounts of corundum or aloxite[5] (aluminum oxide, AL2O3),[16][17] founding the William A. Spinks Company in Chicago[4] after securing a patent on March 9, 1897.[5] Spinks later left the company, but it retained his name and was subsequently run by Hoskins, and later by Hoskins's cousin[4] Edmund F. Hoskin,[18] after Hoskins moved on to other projects.

The William A. Spinks Company product (still emulated by modern manufacturers with slightly different, proprietary silicate compounds) effectively revolutionized billiards,[14][15] by providing a cue tip friction enhancer that allowed the tip to grip the cue ball briefly[5] and impart a previously unattainable amount of "english" (spin),[15] which consequently allowed more precise and more extreme cue ball control, made miscuing less likely, made swerve and massé (curve, or even reversing) shots plausible, and eventually spawned the cue sport of artistic billiards almost a century later. Even the basic draw and follow shots of modern billiards games depend heavily on the effects and properties of modern billiard "chalk".[19]

References

- "C.H.i.C. Timeline 1843–1880" Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, A Guide to the Chemical History of Chicago, Chemical History in Chicago Project, date unspecified; accessed February 24, 2007

- "CHiC Details: Hoskins, William" Archived October 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, A Guide to the Chemical History of Chicago, Chemical History in Chicago Project, date unspecified; accessed February 24, 2007

- Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson (1911). ""William Hoskins" entry". The Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men of the City of Chicago. Vol. 2. self-published. p. 343. The entry can also be found on p. 296 of the orig. 1905 ed. Subsequent editions (1917, 1926) were titled Who's Who in Chicago.

- "The World's Most Tragic Man Is the One Who Never Starts" Archived August 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Clark, Neil M.; originally published in The American magazine, May 1927; republished in Hotwire: The Newsletter of the Toaster Museum Foundation, vol. 3, no. 3, online edition; accessed February 24, 2007. The piece is largely an interview of Hoskins.

- U.S. Patent 0,578,514, March 9, 1897

- "Toasters {} BETHANY MISSION GALLERY". BETHANY MISSION GALLERY. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- "Hoskins Manufacturing Company | People | The Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments". waywiser.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 16, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cutting wire choice for foam cutters and CNC cutting machines -". Hotwire Systems. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Redman, L.V. "The William Hoskins I know". repository.library.northwestern.edu. The Chemical Bulletin. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- George, William F. (2003). Antique Electric Waffle Irons 1900–1960: A History of the Appliance Industry in 20th Century America. Trafford Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 1-55395-632-X. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- "Advanced Level: Reading Comprehension - Sentence Gap Fill - History of the Toaster - Answer Sheet | ESL Lounge". ESL Lounge. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

AEH's proximity to Hoskins Manufacturing and the fact that the patent was filed only two months after the Marsh patents suggests collaboration and that the device was to use chromel wiring. One of the first applications the Hoskins company had considered for chromel was toasters, but eventually abandoned such efforts to focus on making the wire itself.

- "William Hoskins for cue chalk". Days to Remember. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- Tobey, Eddie (November 9, 2006). "Billiards Chalk", EZineArticles.com; retrieved February 24, 2007. Blocked URL: ezinearticles.com/?Billiards-Chalk&id=354398

- "Billiards — The Transformation Years: 1845–1897", Russell, Michael; EZineArticles.com, December 23, 2005; retrieved 24 February 24, 2007. The article was used as the source for CSI, season 6, episode "Time of Your Death" Archived February 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, in which pool chalk plays a small but crucial role; the show perpetuated the "axolite" for "aloxite" error in this article.

- "Aloxite" Archived June 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, ChemIndustry.com database, retrieved February 24, 2007.

- "Substance Summary: Aluminum Oxide" Archived April 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, PubChem Database, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health, retrieved February 24, 2007.

- U.S. Patent 1,524,132, January 27, 1925.

- "Pool Pointers: pool\billiard instruction featuring photos of famous pool players by Billie Billing and Billie Billiard Promotions". billiebilliards.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2018.