William Greer Harrison

William Greer Harrison was a prominent Irish-born citizen in San Francisco during the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century. By profession, he was an insurance agent, but is remembered for his associations with the Bohemian Club, the Olympic Club (for which he was a president), and for his civic contributions.

Biography

Early life

William Greer Harrison was born in County Donegal, Ireland in 1836. He spent his early manhood in New Zealand and afterwards emigrated to San Francisco, United States in the 1870s.

Thames & Mersey Marine Insurance Company

From 1879, he was the manager of the Thames & Mersey Marine Insurance company's underwriting agency in San Francisco. The company had opened its office there in 1876, trading under the name "Messrs. Cross & Co". The early history of the office was chequered, for the agency was held by three representatives in three years. Greer Harrison was the last and most successful of these, building a large and profitable portfolio. During one period of twelve months in the ’eighties, the "Thames & Mersey" insured every shipload of wheat that sailed out of San Francisco without loss. The profit on this alone equalled the whole of the company dividend that year.[1] During this time he resided at 806 Stockton Street, San Francisco.[2] William Greer Harrison retired after 27 years as the senior official of the "Thames & Mersey" on the Pacific Coast of North America, and was succeeded by Louis Rosenthal, who was in turn destined to represent the company there for 34 years.[3]

"Jack the Ripper" allegations

In 1895 William Greer Harrison was the source for an alleged conversation with a Dr Howard in the Bohemian Club, linking the 1888 "Jack the Ripper" murders in Whitechapel, London with an unnamed prominent London physician. This conversation was reported in a number of newspaper articles across the United States, including the Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel (24 April 1895),[4] the Fort Wayne Weekly Gazette (25 April 1895),[5] the Ogden Standard, Utah,[6] the Williamsport Sunday Grit (12 May 1895);[7] the Hayward Review, California (17 May 1895);[8] and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (28 December 1897).[9]

According to Harrison's account, Howard claimed that the murderer was a "medical man of high standing" whose wife alerted his colleagues and the police after becoming alarmed by his erratic behaviour during the period of the murders. Dr Howard "was one of a dozen London physicians who sat as a commission in lunacy upon their brother physician, for at last it was definitely proved that the dread Jack the Ripper was a physician in high standing and enjoying the patronage of the best society in the West End of London." The article goes on to allege that the preacher and spiritualist Robert James Lees played a leading role in the physician’s arrest by using his clairvoyant powers to divine that the Whitechapel murderer lived in a house in Mayfair, London. He persuaded police to enter the house, which turned out to be the home of the physician, who was allegedly removed to a private insane asylum in Islington, London under the name of Thomas Mason.

Civic contributions

In 1904, Harrison was elected as a Director and subsequently Vice-President of the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco. Daniel H. Burnham, the American architect and urban planner, was invited to prepare a plan, which he completed in September 1905, and which was accepted by Mayor Eugene Schmitz.[10] The plan was abandoned after the San Francisco earthquake the following year.

On 19 April 1906, following the San Francisco earthquake, William Greer Harrison was one of fifty citizens nominated by Mayor Schmitz as a Committee of Safety, to oversee the provision of relief to earthquake victims and the restoration of public services.[11]

Death

Harrison died on 3 December 1916 following a paralytic stroke.[12] The press report of his death noted that, despite his advanced age, Harrison participated the previous New Year's Day in the Olympic club's customary cross city run, ending with a plunge in the surf. A bust of him dressed in a runner’s uniform was commissioned by the Olympic Club in his memory, by the sculptor Haig Patigan, a member of the Bohemian Club. This was unveiled on the sixth anniversary of his death on 3 December 1922 and is currently displayed in the West entrance lobby of the club, between Taylor and Madison Streets.[13]

Literary career

William Greer Harrison made a number of attempts at a literary career, as a composer of verse, as a playwright and finally as a writer of factual sports and travel literature.

Playwright career

William Greer Harrison was commissioned by James O’Neill (father of playwright Eugene O'Neill) to write The O'Neill, or the Prince of Ulster — a play based on Hugh Ó Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone, who resisted English authority in Ireland.

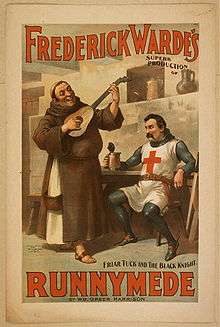

In 1894 Harrison wrote Runnymede, a play based on the story of Robin Hood and written for the Shakespearian actor Frederick Warde.[14] Harrison's treatment portrayed Robin Hood's band not as outlaws, but as loyal subjects of Richard Coeur de Lion, in opposition to John of Anjou. The story was based on the attempts of John to destroy Robin and to gain possession of Marian Lea, Robin's affianced bride. A secondary romance was woven around the love life of Little John of Robin Hood’s band and Margery Josselyn, Marian's companion. Harrison introduced some changes to historical fact for dramatic effect – for example, King Richard I was murdered by his brother John; and having become King, John’s death sentence upon Robin Hood and Friar Tuck was frustrated by his having just signed the Magna Carta.

The play opened in New York in 1895 and closed shortly afterwards, having been severely scorned by the New York critics.[15] Upon his return to San Francisco, Harrison explained that the play's failure was due to the cultural deficiencies of New York society. He is quoted as saying:

The Bohemian Club of San Francisco represents more refinement, more intelligence, and more culture than can be found in the whole City of New-York, so far as it is possible for a visitor to see it. Judging from such opportunities as I had of seeing New-York mean, and I saw them in the best of their clubs, they do not know what is really meant by culture. Novelty and sensation they understand. I say this not from any hard feelings toward New-York, for the cause of their lack of knowledge is readily seen. It arises from their slavish life. They are slaves to their business, and when they go to the theatre they want to see something that will make them laugh.[16]

Travel and sports books

William Greer Harrison wrote a number of travel and sports books, including The Outdoor Life of California (1905) and Making a Man; a manual of athletics (1915).

Feud with Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Bierce, satirist and fellow Bohemian Club member, was a long term critic of Harrison, likening his verse to "a roadside pump replenishing a horse trough"[17] When the young Jewish poet David Lesser Lezinsky shot himself on 4 July 1895,[18] Bierce was widely blamed, being accused of mocking the young writer for anti-Semitic reasons. William Greer Harrison joined in the criticism though a series of angry letters published in local newspapers.[19]

After Harrison’s death in 1916, Bierce wrote an obituary parodying his literary style and mocking his alleged use of his wealth to buy approval:

Here lies Greer Harrison, a well cracked louse

So small a tenant of so big a house!

Who loved to loll on the Parnassian mount,

His pen to suck and all his thumbs to count.

What poetry he'd written but for lack

Of skill, when he had counted, to count back!

Alas, no more he'll climb the sacred steep

To wake the lyre and put the world to sleep!

To his rapt lip his soul no longer springs

And like a jaybird from a knot-hole sings.

No more the clubmen, pickled with his wine,

Expand their ears and hiccough: "That's divine!"

The genius of his purse no longer draws

The pleasing thunders of a paid applause.

All silent now; nor sound nor sense remains,

Though riddances of worms improve his brains.

All his no talents to the earth revert,

And Fame concludes the record: "Dirt to dirt!

References

- Thames & Mersey Marine Insurance Company Limited 1860-1960, publisher Rockliff Bros Ltd, 44 Castle Street Liverpool, p40-41

- San Francisco City Directory 1880

- Thames & Mersey Marine Insurance Company Limited 1860-1960, publisher Rockliff Bros Ltd, 44 Castle Street Liverpool, p47

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/fort_wayne_weekly_sentinel/950424.html

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/fort_wayne_gazette/950425.html

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/ogden_standard/950424.html

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/williamsport_sunday_grit/950512.html

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/hayward_review/18950517.html

- http://www.casebook.org/press_reports/brooklyn_daily_eagle/971228.html

- http://www.netzaesthetik.de/Servin/url/burnham.html

- The New York Times, 19 April 1906, reproduced at http://news.quickfound.net/cities/san_francisco.html

- Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada) dated 4 December 1916

- Ellison, Joan, ed., "A Survey of Art Work in the City and County of San Francisco," San Francisco, CA: Art Commission, City and County of San Francisco, 1975, no. 710

- The New York Times 21 December 1894

- The New York Times 7 October 1895

- The New York Times 8 October 1895

- Ambrose Bierce: alone in bad company, Roy Morris ISBN 0-19-512628-9 p222,

- San Francisco Call, 5 July 1895

- Gale, Robert L. An Ambrose Bierce companion Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-313-31130-7