William Goffe

William Goffe (1605?–1679?) was an English Roundhead politician and soldier, perhaps best known for his role in the execution of King Charles I and later flight to America.

William Goffe | |

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | ca. 1605 England |

| Died | ca. 1679 New England |

| Nationality | English |

Early life

He was son of Stephen Goffe, puritan rector of Bramber in Sussex, and brother of Stephen Goffe (Gough), royalist agent. His father was deprived of his living in 1605 for his part in organising the puritan petitions to James I.[1] He began life as an apprentice to a London salter, a zealous parliamentarian. Goffe was a man of religious feeling, nicknamed "Praying William".[2]

By his marriage with Frances, daughter of General Edward Whalley, he became connected with Oliver Cromwell's family and one of his most faithful followers. He was imprisoned in 1642 for his share in the petition to give control of the militia to the parliament.[3]

Civil War years

On the outbreak of the English Civil War he joined the army and became captain in Colonel Harley's regiment of the New Model Army in 1645.[3]

He was a member of the deputation which on 6 July 1647 brought up the charge against the eleven Presbyterian members. In late 1647 Goffe played a prominent part in the famous debates of the army council at Putney. The contemporary record of the debates clearly reveals his religious and political radicalism.[1] He was active in bringing King Charles I to trial and signed the death warrant. In 1649, he received an honorary M.A. at Oxford.[3]

He distinguished himself at the Battle of Dunbar, commanding a regiment there and at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. [3]

Major-general

He assisted in the expulsion of Barebone's Parliament in 1653 and took an active part in the suppression of Penruddock's rising in the west country of July 1655. In October 1655 during the Rule of the Major-Generals he was appointed major-general for Berkshire, Sussex and Hampshire. Meanwhile, he had been elected member for Yarmouth in Norfolk in the parliament of 1654 and for Hampshire in that of 1656. He encouraged the Hampshire justices of the peace to suppress unlicensed alehouses in their county, and attempted to curtail the evangelising activities of itinerant Quaker preachers, towards whom he was extremely hostile.[1] He supported the proposal to bestow a royal title upon Oliver Cromwell, who greatly esteemed him, and was included in the newly constituted Upper House. He obtained Lambert's place as major-general of the Foot and was even thought of as a fit successor to Oliver Cromwell.[3]

As a member of the committee of nine appointed in June 1658 on public affairs, he was witness to the Protector's appointment of Richard Cromwell as his successor. He supported the latter during his brief tenure of power and his fall involved his own loss of influence. In November 1659 he took part in the futile mission sent by the offices of the London cabal of the New Model Army to General George Monck, the English military governor of Scotland.[3]

In New England

In 1660, during the Restoration, he escaped with his father-in-law, General Edward Whalley, to Massachusetts. They landed in Boston on 27 July 1660, and settled in Cambridge. When the news arrived in Boston, on the last day of November, that the act of indemnity passed by parliament in August excepted them from its provisions, the government of the colony began to be uneasy, and a meeting of the council was held on 22 February 1661 to consult as to their security.[4]

Four days later, the two fled for New Haven, Connecticut, arriving on 7 March 1661.[4] There John Dixwell, also condemned as a regicide, was living under an assumed name. They were housed by Rev. John Davenport. After a reward was offered for their arrest, they pretended to flee to New York City, but instead returned by a roundabout way to New Haven. In May, the Royal order for their arrest reached Boston, and was sent by the Governor to William Leete, Governor of the New Haven Colony, residing at Guilford. Leete delayed the King's messengers, allowing Goffe and Whalley to disappear. They spent much of the summer in Judges' Cave at West Rock.[5]

Letters to Dr. Increase Mather and others give hints as to Goffe's whereabouts, but very little is clear, perhaps due to his desire not to be captured and executed. He appears to have passed the rest of his life in exile in New England, separated from his wife and children, under one or more assumed names.[5]

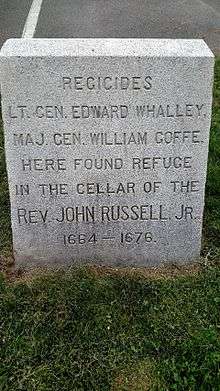

Tradition has him sheltering for a decade in the home of Rev. John Russell at Hadley, Massachusetts, reappearing, according to legend, to lead the town's defence during King Philip's War, giving rise to the legend of the Angel of Hadley. [6]After the war in July, 1676, Goffe is last seen in Hadley and went off into Hartford and was nearly arrested in 1678 by being recognized but once again escaped in time. By 1679, no record of Goffe’s whereabouts are and was presumed dead shortly after.

Another traditional account has him later living in Stow, Massachusetts under the alias of John Green, where his sister Mary [Green] Stevens resided, dying in Stow, and being buried in the Stow Lower Cemetery under an unmarked granite slab.[7][8] However, his dying in Stow is debunked[9]: in fact, Mary [Green] Stevens was the sister of Capt John Green who died in Stow in 1688.[10] Another legend is that he died in Hartford, Connecticut under an alias about 1680.[11] A Phillip Goffe settled in Wethersfield, Connecticut prior to 1649,[12] where his granddaughter Mabel Goffe in 1707 married Daniel Andrews; allegedly Mabel Goffe was a descendant of William Goffe.[13] However, this is unlikely as of William Goffe's children only two married and had issue: a daughter Frances; while Williams Goffe's surviving son Richard and his descendants were residents of Waterford, Ireland. Burke's Peerage reports that William Goffe died in New Haven, Ct in 1680.[14]

The three regicides are commemorated by three intersecting streets in New Haven ("Dixwell Avenue", "Whalley Avenue", and "Goffe Street"), Hadley, and in some neighbouring Connecticut towns as well.

See also

Notes

- Durston 2008.

- Manganiello 2004, p. 225.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 190.

- Wilson & Fiske 1900.

- Firth 1890.

- However this is debunked-see King Philip's War: Based on the Archives and Records of Massachusetts …

- "Colonial Stow". Town of Stow website. Virtual Towns & Schools. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Crowell, Preston R. (1933). Stow, Massachusetts 1683-1933. Stow, Massachusetts. pp. 26–35.

- Myths of Stow and Maynard 2016

- History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical ..., Volume 1, p.660

- Myths of Stow and Maynard, 2016

- The Descendants of John Porter of Windsor, Conn. 1635-9, Volume 2

- Genealogical and Family History of Central New York: A Record of ..., Volume 2

- Burke's Peerage p.855

References

- Durston, Christopher (January 2008) [2004]. "Goffe, William (d. 1679?)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10903. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Firth, Charles Harding (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 71–73.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. p. 225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Attribution

Further reading

- Death Warrant of Charles I, House of Lords Record Office, retrieved 1 May 2013

- Cogswell, Frederick Hull (October 1893), "The Regicides in New England", New England Magazine, Boston, 15 (2): 188–201

- Major, Philip (2016), "'A poor exile stranger': William Goffe in New England", Literatures of Exile in the English Revolution and its Aftermath, 1640-1690, Routledge, ISBN 9781351921916

- Marshall, Henrietta Elizabeth (1917), "Chapter 31: The Hunt for the Regicides", This Country Of Ours; the story of the United States, New York: George H. Doran company

- Paige, Lucius (1877), History of Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1630-1877. With a genealogical register, Boston : H. O. Houghton and company; New York, Hurd and Houghton, pp. 67–71, 563

- Stiles, Ezra (1794), History of Three of the Judges of Charles I, Whalley, Goffe, Dixwell, Hartford