William Dick of Braid

Sir William Dick of Braid (1580–1655) was a 17th-century Scottish landowner, banker and merchant who served as Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1638 to 1640.[1] His fortunes took him from being "the richest man in Scotland" in 1650 to his death as a pauper a few years later.[2]

Life

He was born in 1580 at Braid Castle, then south-west of Edinburgh (now enveloped by the city) close to what is now Hermitage of Braid.[3] He was the son of John Dick and his wife, Margaret Stewart. John Dick had much land in Orkney and had also assembled much wealth trading with Denmark.[4]

As a banker in 1617 he loaned £66,666 to the treasurer-depute Gideon Murray for the visit of James VI and I to Scotland, indicating his enormous wealth and power.[5] In 1639 he loaned the Covenanting Army under James Graham, Marquess of Montrose a staggering £200,000 (£24 million in current terms).[6]

He had an Edinburgh townhouse on the Royal Mile between Byers Close and Advocates Close, immediately opposite St Giles Cathedral. Much of this building (which he built in 1630) still survives (behind a new office on Advocates Close) and is known by the name of an earlier occupier of the site as Adam Bothwell's House.[7] Dick would have had offices, his "bank", here at 369 High Street.[8] An interior from around 1630 may have been added by Dick as it includes a built in safe within the timber panelling. He acquired this building from John Byres of Coates, also a banker.[9]

In 1638 he succeeded John Hay of Lands as Provost of Edinburgh. He was succeeded in turn in 1640 by Alexander Clerk of Pittencrieff.[10] He was knighted in 1641 by King Charles I of England, to whom he had loaned large sums.[6]

During the English Civil War his Royalist sympathies came home to roost when Cromwell's troops camped at the Braid and demanded compensation for his loyalist support. This he paid. He afterwards went to London to try to recover this money. His efforts instead ended with his being heavily fined by the Cromwellian authorities.

He died on 19 December 1655. Although some records state he died in prison, he died in private lodgings in Westminster in London. A collection was required to pay for his funeral and his grave had no stone memorial and is lost.[4]

Following his death his Edinburgh property was sold to John Keith, 1st Earl of Kintore.[4] The Royal Mile house was misidentified as Adam Bothwell's house around 1870 during the renewal of interest in "romantic history" by Victorian writers and is a category A listed building.[11][12] All that survives of Braid Castle is the doocot and remnant boundary walls and foundations amongst the trees in the Braid Woods.

"Provost Dick" is mentioned in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Heart of Midlothian.[13]

Family

He married Elizabeth Morrison.

Their eldest son and heir was John Dick of Braid (1610-1642) who died young. Other children included Alexander Dick of Heugh (1618-1663), Andrew Dick, William Dick (Baron Grange), Lewis Dick, Elizabeth Dick and Janet Dick. Alexander Dick was forefather to the Dick-Cunyngham baronets and the Dicks of Prestonfield, including James Dick of Prestonfield, Lord Provost 1679/81 .

Bibliography

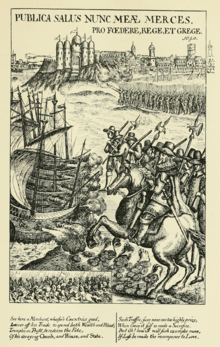

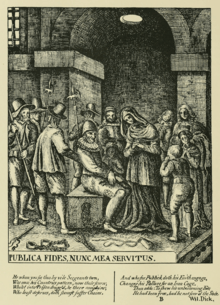

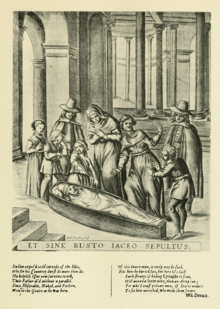

- The Lamentable Estate and Distressed Case of Sir William Dick, published in 1657, contains the petition of his family and other papers, the originals of which are included in the Lauderdale Papers, Addit. MS. 23113. His case is set forth in verse as well as in prose, and is pathetically illustrated by three copperplates, one representing him on horseback superintending the unloading of one of his rich argosies, the second as fettered in prison, and the third as lying in his coffin surrounded by disconsolate friends who do not know how to dispose of the body. The tract, of which there is a copy in the British Museum, is much valued by collectors, and has been sold for 52l. 10s.[2]

- Acts of the Parliament of Scotland

- Balfour's Annals

- Spalding's Memorials

- Gordon's Scots Affairs

- State Papers, Dom. Ser. 1652-3

- Douglas's Baronage of Scotland, i. 269-70

- Notes and Queries, 3rd ser. vi. 457.

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Smith, Jane Stewart (1898). The Grange of St. Giles, the Bass, and the other baronial homes of the Dick-Lauder family. Edinburgh : Printed for the author by T. and A. Constable. pp. 45–57. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1885–1900). Dictionary of national biography (Vol. 18 ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- http://www.stravaiging.com/history/castle/braid-castle

- ODNB: William Dick

- John Imrie & John Dunbar, Accounts of the Masters of Works, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1982), pp. xxxii-xxxiii, 84, 89-93: Julian Goodare, State and Society in Early Modern Scotland (Oxford, 1999), p. 130: W. MacNeill and P. MacNeill, 'The Scottish Progress of James VI', SHR, 75 (1996), pp. 47-50: John Spottiswoode, History of the Church of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1850), p. 239.

- http://www.scottish-places.info/people/famousfirst1272.html

- Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh, by Gifford, McWilliam and Walker

- 'Adam Bothwell's House', HES RCAHMS Canmore

- The Closes and Wynds of the Old Town, The Old Edinburgh Club

- History of Edinburgh from its Foundation to the Present Time, vol 3, p.227: Civil Government

- City of Edinburgh Council: Listed Buildings

- 1875 OS map

- Heart of Midlothian, Walter scott