William Careless

Colonel William Careless (surname variants include Carelesse, Carless, Carles and Carlis)[1] was a Royalist officer of the English Civil War. It has been estimated in various written sources that he was born c. 1620, however, it is more likely that he was born c. 1610.[2] He was the second son of John Careless of Broom Hall, Brewood, Staffordshire, and his wife Ellen Fluit.[3][4][5] He is chiefly remembered as the companion of King Charles II when the fugitive monarch hid in the Royal Oak following his defeat at the Battle of Worcester. His surname was changed to Carlos, the Spanish for Charles, by order of Charles II. He died in 1689.

William Careless, later Carlos | |

|---|---|

King Charles II and Colonel William Careless in the Royal Oak by Isaac Fuller | |

| Born | c. 1610 Broom Hall, Brewood, Staffordshire |

| Died | 1689 London |

| Buried | St. Mary the Virgin and St. Chad churchyard, Brewood. |

| Allegiance | Royalist |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Commands held | A troop and later a regiment of cavalry, the garrison of Tong Castle, officer of the Royal Guard, |

| Battles/wars | English Civil War, Bolton Massacre, Battle of Marston Moor, Battle of Worcester, Battle of the Dunes (1658) |

Career

The First Civil War

Careless was a member of a recusant Roman Catholic family of Royalist sentiments. After the outbreak of hostilities in 1642 Careless raised a troop of cavalry to fight for Charles I, which he commanded as a captain in the regiment of Thomas Leveson. This regiment was largely officered by men from the Catholic enclave of south Staffordshire.[6] He was the captain of the Royalist garrison at Lapley House, Staffordshire, in 1643, and was appointed governor of Tong Castle, Shropshire, in April 1644.[7] He appears to have rejoined his regiment to take part in Prince Rupert's campaign to relieve the siege of York. Careless (as William Carlis) has been listed as one of the two captains of Leveson's Horse present at the Bolton Massacre, an action controversial for the indiscriminate killing of Parliamentarian defenders and civilian inhabitants.[8] His regiment then went on to fight as part of the right-wing cavalry, commanded by Lord Byron, at the Battle of Marston Moor in July 1644.[9] Following this serious Royalist defeat Careless is next recorded in his native area of the English Midlands, when in December 1644 he was captured in a skirmish with Parliamentarian forces near Wolverhampton. In April 1645 he was recorded as one of the prisoners that the Parliamentarians were holding in the High House, Stafford.[10] After his release Careless served in Ireland, lived in Lower Germany (Netherlands) for a time and became an officer in the Spanish army.[5][11] He returned to England in or before 1650, and spent nine months in and around his home in Brewood before once again taking up arms in the Royalist cause.[10]

The campaign of 1651

.jpg)

After the execution of Charles I, his son Charles II invaded England at the head of a largely Scottish army. Careless joined the king with a small force, described as a regiment of horse,[12] as he advanced on Worcester and fought as a major under Lord Talbot at the Battle of Worcester. The Royalist forces were very heavily defeated. Careless fought to the end, covering the King's flight alongside a handful of others including the Earl of Cleveland, Sir James Hamilton, Colonel Thomas Wogan and Captains Hornyhold, Giffard, and Kemble. Careless and his companions made a number of desperate cavalry charges down Sudbury Street and High Street, though heavily outnumbered. Hamilton and Kemble were badly wounded, and a number of troopers were killed. Their actions allowed King Charles to escape the city by St. Martin's Gate.[13] Careless reputedly witnessed the death of the last man to be killed in the battle.[14]

Following his catastrophic defeat, King Charles sought refuge at Boscobel House where, as he related to Samuel Pepys in 1680, he met Major Careless. Charles was being hidden and cared for by the Penderel family who, as tenants of the Giffard family, were living at Boscobel House. Careless, who was a local man,[15] suggested that the house was unsafe and recommended that the king hide in a large pollarded oak tree in the woodlands of Boscobel (6 Sep 1651). The king and Careless took some food and drink into the tree and were gratified that Parliamentarian soldiers searched the woodland intensively without detecting them. The king, who was exhausted, slept in the tree for some of the time, being prevented from falling by Careless' support. Charles spent the night hiding in one of Boscobel's priest holes, Careless in another.[16] The following day Careless killed and butchered a sheep with his dagger, the mutton was afterwards cooked by the king himself. Being too well known locally, and not wishing to draw attention to the disguised Charles, Careless parted from the king later the same day (7 Sep 1651).[16][17][18]

A contemporary armorial locket containing a miniature portrait of William Careless is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, (see "External links" below). The inscription within the locket runs:

- "Renowned Carlos! thow hast won the day

- (Loyalty Lost) by helping Charles away,

- From Kings-Blood-Thirsty-Rebels in a Night,

- made black with Rage, of theives, & Hells dispight

- Live! King-Loved-Sowle thy fame be Euer Spoke

- By all whilst England Beares a Royall Oake"

Exile

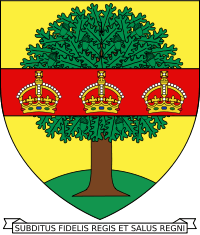

Careless escaped England independently of King Charles, fleeing to France; he was the first person to inform Charles' sister, Mary, Princess of Orange, of her brother's safety.[19][20] In 1656 William Careless, with the rank of colonel, is listed as a captain in the King's Royal Regiment of Guards the lineal predecessor of the Grenadier Guards.[21] At Brussels he received, in 1658 by letters patent under the Great Seal in the name of Carlos, a coat of arms incorporating an oak tree and three crowns representing the three kingdoms of the British Isles; an oak-leaf civic crown formed part of the crest.[22][23]

Careless served with his regiment at the Battle of the Dunes (14 June 1658), near Dunkirk; this battle was fought between a Spanish army, with an allied British Royalist force commanded by the Duke of York (later King James II), and a French army with Cromwellian English (Commonwealth) allies. The Spanish army was defeated and Colonel Careless was made captive, however, he was soon released on a "half ransom." During the battle Careless' regiment stood firm when all the regiments around it fled; the King's Guards were eventually persuaded to surrender when two of their officers had been conducted to a nearby eminence from which they could see that the rest of the army they belonged to had been swept from the field or had already surrendered.[24]

Later life

He returned to England with Charles II in 1660, and after the Restoration Careless was granted (with 2 others) the lucrative proceeds of tax on hay and straw brought into London and Westminster, the right to sell ballast to shipping on the Thames and the office of inspector of livery horsekeepers (1661).[5][25] In 1660 Careless, along with Charles Giffard and others who helped in King Charles' escape, was proposed as a knight of The Order of the Royal Oak and was listed under those persons resident in London and Middlesex. As for all proposed knights Careless' income was recorded, and this was £800.00 per annum. Charles II was persuaded that the new order of chivalry would prove politically and socially divisive as it only rewarded those who had aided him in adversity and those who were ardent Royalists. He therefore reluctantly abandoned the scheme.[26]

Careless was made a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber in 1666.[27] Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber were empowered to execute the King's verbal command without producing any written order; their person and character being deemed sufficient authority. With his close friend Charles Giffard, Careless was prominent in petitioning the king for favour on behalf of various people involved in the escape of Charles II after Worcester, or their dependants. Many of these petitions were successful and they materially benefitted friends and former neighbours of Careless.

In 1678, along with other Catholics who aided King Charles after Worcester, he was made exempt from all anti-Catholic legislation.[28] Careless was evidently loyal to King Charles' successor, James II, as he was paid a bounty of £300 from that monarch's secret service fund in 1687.[20]

Sources variously give Careless the rank of captain, major and colonel. In the historical tract "Boscobel" it is stated that Careless was a major at the time of the Battle of Worcester.[13] It would appear that he was promoted to colonel sometime between 1651 and 1656, when he is first recorded as holding the rank. However, it is possible that he was acting as the major for his regiment in 1651 whilst holding the substantive rank of colonel.

Colonel William Careless is recorded as living in Hallow, Worcestershire in the 1680s; he died in London, and was buried in his native Brewood, 28 May 1689.[14] A memorial to William Careless is to be found in the church of St Mary the Virgin and St Chad, Brewood; he is believed to be buried in the churchyard though his original monument no longer exists; a replacement headstone was erected in Victorian times.

Family

William Careless married the sister of Sampson Fox, who was a trooper under his command, and also a Roman Catholic.[29] His sons were: William, born c. 1631, who became a Jesuit priest (admitted to the Jesuit College in Rome in 1655 under the name Dorrington) died 26 Jan 1679, Thomas, born c.1640, died 19 May 1665, and an adopted son, Edward Carlos (the eldest son of his brother John), born 6 October 1664, died 10 September 1713.[5][30][31][32][33] His son William was in exile in Lower Germany with his father after 1645 and fought beside him at Worcester. He was separated from his father during the battle and made his way to London. His religious vocation was inspired by witnessing the execution of Saint John Southworth. A signed document dating to 1655 shows that William was using the surname Carlos at this date, before his father's officially recognised name change.[34]

The Careless family of Brewood lost most of their land and social prominence in the 1720s when Charles Carlos, the eldest son of the Edward adopted by Colonel William Careless, squandered his inheritance. Charles is described in a court case as having "impoverished the [Broom Hall] estate." On 6 April 1716 Charles Carlos (under the name Charles Careless) petitioned, along with other Catholic descendants of those who aided Charles II in his escape, the protection of George I against anti-Catholic legislation.[35]

Legacy

In 2013 a memorial plaque to William Careless (as William Carlos) was attached to the base of a statue of Charles II, by Grinling Gibbons, in the grounds of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.[36]

Oak Apple Day or Royal Oak Day was a national holiday celebrated in England for a number of centuries, on 29 May, to commemorate the restoration of the English monarchy. The oak symbolism referenced Careless' successful ploy of hiding Charles II in the oak tree at Boscobel.

A commemorative medal was struck with the inscription "GOD . BLES . MY . LORD . WILMOT . LADY . LANE . COL . CARLES . CAPT . TEDERSAL." the names are those of the principal persons who aided Charles II in his escape after Worcester. The medal shows (obverse) a view of the walls and fortifications of Worcester with defenders; outside, Charles on horseback attended by the four Penderels and Yates, and before him a company of soldiers (British Museum catalogue: MB1p394.19).

The Royal Oak was adopted as a personal badge by Charles II. It is still a symbol of the British monarchy and of England, and was displayed on the reverse of a pound coin issued in 1987.

The Royal Oak is the third most common pub name in Britain.

The income granted to the Penderel brothers is still paid to some of their descendants to this day. However, of the payment, from the various sources of income bestowed by Charles II, which was granted to the descendants of the heirs of William Careless some was suspended by the British government in 1822, and the remainder early in the 20th century.[37]

Fiction

William Careless appears as a very prominent character in the novel 'Boscobel or the Royal Oak: A Tale of the Year 1651,' by William Harrison Ainsworth, first published in 1871. As William Carlis, he is also found in 'Royal Escape' (1938) a historical novel written by Georgette Heyer.

Notes

- The surname is most frequently recorded as "Carelesse" in the contemporary parish records of Brewood. The original meaning of the surname indicated 'a carefree nature' - that is being without worries - rather than the more modern primary meaning of 'taking insufficient care.'

- His son William recorded that he was thirteen when his father was the governor of Tong Castle in 1644, making his father's birthdate more likely to have been around 1610 than 1620 - Foley, p. 180.

- Grammont, pp. 514-515

- Grazebrook, p.102 - the family were anciently seated at Albrighton, Shropshire - back to the time of Richard II, see: Griffiths, George (1894) A History of Tong Shropshire, London, p. 180 also Antiquities of Shropshire, Vol II, (1855) London, pp. 157-159. The family probably descend from Roger Careles or Carles c. 1270-c.1335, King's Fermor and lord of the manors of Albrighton and Ryton.

- William Salt Library MS

- Bennett, p. 11

- Auden, p. 30

- Casserly, p. 188

- Casserly, pp. 126-129

- Greenslade, p. 115

- Foley, p. 180

- Hamilton, Ch I, p. 14 (footnote) The cavalry regiment was largely composed of Worcestershire gentry and their retainers plus a few of the gentry, such as Careless, from neighbouring counties.

- Grammont, p. 490

- Smith, p.41

- His home was a mere 2 miles from Boscobel House

- Fraser, pp. 150-152

- Grammont, pp. 462, 503 and 506

- Lyon, p. 240

- Fraser p. 155

- Leslie, p. 105

- Hamilton, Ch. I, p. 9.

- Smith, p.41.

- Grazebrook p. 103. The Latin motto granted with the coat of arms can be translated as 'A subject loyal to his king and the good of the kingdom." King Charles is said to have remarked that Careless was an inappropriate name for someone who had shown so much care of his monarch's safety, hence the change of surname to Carlos.

- Hamilton, pp. 24-27. The soldiers of the regiment surrendered on terms: that they would not be plundered and would not be handed over to the Commonwealth English who were fighting alongside the French.

- Greenslade, p. 131

- Burke, p. 690.

- Carlisle, pp.176,177)

- House of Lords Journal Volume 13, 7 December 1678 - "ORDERED, by the Lords Spiritual and Temporal in Parliament assembled, That ... Colonel William Carlos, ... who were instrumental in the Preservation of His Majesty's Person after the Battle at Worcester, or such of them as are now living, shall, for their said Service, live as freely as any of His Majesty's Protestant Subjects, without being liable or subject to the Penalties of any of the Laws relating to Popish Recusants; and that a Bill be prepared and brought into this House for that Purpose." From: 'House of Lords Journal Volume 13: 7 December 1678', Journal of the House of Lords: volume 13: 1675-1681 (1767-1830), pp. 406-408. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=11622 Date accessed: 7 June 2010.

- Pennington and Roots, p. 218

- Auden, pp. 28-30

- Hughes, pp. 395-397

- Beresford, pp. 204-205

- Archaeologia Cambrensis, p. 116.

- Foley, pp. 180-181.

- Fea - Flight of the King - pp. 310-311

- Lyon, p 241.

References

- Archaeologia Cambrensis (1859). Vol. V, Third Series, London.

- Auden, John, E. (2004) Joyce Frost (Ed.) Auden's History of Tong - Volume 2. Bury St. Edmunds. ISBN 1-84549-010-X

- Bennett, M., (2003) Roman Catholic Royalist Officers in the North Midlands, 1642-1646. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Vol. 6, Issue 2

- Beresford, W, Rev. (Ed.) (1909) Memorials of Old Staffordshire, London.

- Burke, J. (1834) A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland Vol I, London.

- Carlisle, Nicholas (1829). An inquiry into the place and quality of the Gentlemen of His Majesty's ... privy chamber ..., Payne and Foss.

- Casserly, D. (2010) Massacre: The Storming of Bolton, Amberly Publishers, Stroud, Gloucestershire. ISBN 978-1-84868-976-3

- Fea, A. (1897, second ed. 1908) The Flight of the King, London.

- Foley, Henry (1877) Records of the English province of the Society of Jesus Vol. I, Burns and Oates, London.

- Fraser, Antonia (1979) King Charles II, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Grammont, Count. (1846) Memoirs of the Court of Charles the Second and the Boscobel Narratives, edited by Sir Walter Scott, Publisher: Henry G Bohn, York Street, London.

- Grazebrook, Henry, S. (1873) The Heraldry of Worcestershire. London.

- Greenslade, Michael, (2006) Catholic Staffordshire, Leominster. ISBN 0-85244-655-1

- Hamilton, F.W., Sir (1874) The Origin and History of the First or Genadier Guards. Publisher: John Murray, London.

- Hughes, J. (Ed.) (1857) The Boscobel Tracts Edinburgh and London.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). . Dictionary of National Biography. 9. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Lyon, C.J. (1851) Personal History of King Charles II. Thomas George Stevenson, Edinburgh.

- Pennington, D.H. and Roots, I.A. (eds.) (1957) The Committee at Stafford 1643-1645: The Order Book of Staffordshire County Committee, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

- Smith, James Hicks. (1874) Brewood: a résumé historical and topographical. Publisher: W. Parke, London.

- William Salt Library (Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Cultural Heritage), RefNo S. MS. 478/8/88 "Two letters from R. M. Hopper to Thomas Fernyhough about the Carlos/Carliss family, and a pedigree showing his descent from them." Biographic information derived from the letters and other sources -

External links

- The Victoria and Albert Museum has a locket engraved with the arms and motto that were granted to Colonel William Careless. Inside the locket is a portrait of Careless.

- William Salt Library (Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Cultural Heritage) RefNo S. MS. 478/8/88 and biographic information