Wilberforce Cemetery

Wilberforce Cemetery is a heritage-listed cemetery at Clergy Road, Wilberforce, City of Hawkesbury, New South Wales, Australia. It was laid out by surveyor James Meehan and established in 1811. It is also known as St John's Church of England Cemetery. It is owned by Hawkesbury City Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 20 August 2010.[1]

| Wilberforce Cemetery | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Wilberforce Cemetery, taken from the south east | |

| Location | Clergy Road, Wilberforce, City of Hawkesbury, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33.5541°S 150.8426°E |

| Built | 1811– |

| Architect | Surveyor James Meehan |

| Owner | Hawkesbury City Council |

| Official name: Wilberforce Cemetery; St John's Church of England Cemetery | |

| Type | state heritage (landscape) |

| Designated | 20 August 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1837 |

| Type | Cemetery/Graveyard/Burial Ground |

| Category | Cemeteries and Burial Sites |

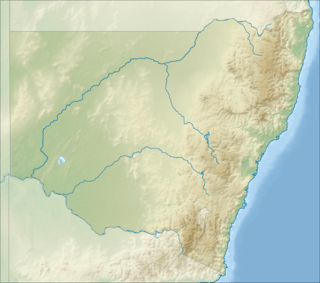

Location of Wilberforce Cemetery in New South Wales | |

History

The Darug (various spellings) occupied the area from Botany Bay to Port Jackson north-west to the Hawkesbury and into the Blue Mountains. The cultural life of the Darug was reflected in the art they left on rock faces. Before 1788, there were probably 5,000 to 8,000 Aboriginal people in the Sydney region. Of these, about 2,000 were probably inland Darug, with about 1,000 living between Parramatta and the Blue Mountains. They lived in bands of about 50 people, and each band hunted over its own territory. The Gommerigal-tongarra lived on both sides of South Creek. The Boorooboorongal lived on the Nepean from Castlereagh to Richmond. Little information was collected about the Aboriginal people of the Hawkesbury before their removal by white settlement so details of their lifestyle have to be inferred from the practices of other south-eastern Aborigines. It is believed they lived in bark gunyahs. The men hunted game and the women foraged for food.[1]

On 15 December 1810, Macquarie issued an Order laying out five towns along the Hawkesbury River. One at Green Hills would be called Windsor. Another at Richmond Hill District would be called Richmond. A third in the Nelson district would be named Pitt Town. The village in the Phillip district would be called Wilberforce and the fifth in the Evan district was Castlereagh. Nearby settlers would be allotted sites on these towns to build.[1]

Wilberforce developed as an area of small farms with few large landholders.[2] Situated on the northern bank of the Hawkesbury River with more difficult access, it did not attract the attention of large landholders. A community with a sizeable representation of freed convicts emerged and was maintained over the years as their families grew.[1]

An early burial ground was located at Portland Head, later known as Ebenezer and may have been in operation as early as 1810.[3]Otherwise, deceased people were often buried on their farms.[1]

On 6 December 1810, Macquarie selected the site for Wilberforce. These town sites would provide refuges from floods for those farming nearby lands. Surveyor James Meehan was instructed to lay out a town at Wilberforce on 26 December 1810.[3] Macquarie also selected land for a church on high ground near this site. Meehan laid out 2 acres for a burial ground at Wilberforce on 5 January 1811.[4] On 2 February 1811, Macquarie instructed Reverend Samuel Marsden to consecrate the burial grounds at towns on the Hawkesbury including Wilberforce. Surveyor Evans would show him the areas set aside.[5] Macquarie issued an order on 11 May 1811 that deceased persons must be buried in consecrated burial grounds and no longer on their farms and that the local settlers were to enclose these burial grounds as soon as possible.[6] Reverend Cartwright was paid £10 before 1 July 1812 for "enclosing the Burial Ground at the Township of Wilberforce".[1]

The earliest burials in Wilberforce Cemetery were of three drowned men, James Hamilton (Hambleton), Joseph Ware and John Tunstal on 13 December 1811, but their gravesites are unknown.[7] Margaret Chaseling was buried in the cemetery in October 1815 and is the oldest burial for which the site is known.[8] Soon afterwards, Anthony Richardson, a Second Fleet arrival, was buried on 4 February 1816. His burial marker is the oldest to survive.[9] A schoolhouse-cum-chapel was also erected on the church site nearby so that the Macquarie ideal of the church, school and burial ground on the highest point demonstrating order and religion was realised in the town of Wilberforce.[1]

In July 1822, Macquarie reported that at Wilberforce he had erected, "A Burial Ground of 4 Acres Contiguous to the Temporary chapel, enclosed with a Strong Fence." It is notable that the measurement does not agree with the area as laid out by surveyor Meehan, which was 2 acres (0.8 ha). The area of the oldest section is close to 2 acres. Macquarie appears to have simply made an error when listing his achievements in the colony.[1]

Until 1826, burials at Wilberforce were recorded in the register for St Matthew's at Windsor. A separate burial register for Wilberforce Cemetery commenced that year.[10][1]

Between 1811 and 1825, there were a considerable number of burials in the cemetery who were early ex-convict arrivals. Many were later joined in the cemetery by their families and descendants. The existing spatial configuration of the Cemetery is also striking. A high number of older grave markers also survive, many of them for ex-convicts who arrived in the earlier period. Of all Macquarie's cemeteries, Wilberforce has the most interments with the highest proportional representation of ex-convict settlers from the First to the Third Fleets. Windsor has more convict burials but they arrived later. Richmond cemetery is dominated by free arrivals. The original Pitt Town cemetery does not exist anymore. Castlereagh cemetery was largely unused. Liverpool cemetery has been destroyed. Of the burials at Wilberforce from 1811 to 1825, 36% were interments of convicts who arrived before 1800.[11] The orientation of the graves is such that they face from north-east to south-west, so that the north-eastern boundary is the "front" of the cemetery.[12][1]

Though the cemetery was placed in the control of the Church of England, there are burials of people from other denominations as well, such as Roman Catholics and Methodists.[13][1]

The burial ground was officially appropriated as a Church of England Cemetery in 1833.[14] From the earliest days, a road to the north and Kurrajong passed close to the eastern side of the cemetery. It was a rough track not officially gazetted but its existence was shown on the earliest plans of the town.[15][1]

On 22 August 1894, Surveyor C. R. Scrivener completed a survey of two additions to the cemetery for a General Cemetery, with 1 rood 20 perches adjoining the Church of England Cemetery and another of 1 acre across the roadway.[16] On 4 July 1896, an area of 1 acre was dedicated as a General Cemetery on the opposite side of the unnamed road.[17] It appears to never have been used for interments.[1]

The area measuring 1 rood 20 perches immediately adjacent to the older cemetery between the 1811 cemetery and the unnamed road was dedicated as a General Cemetery on 22 August 1906. It was later approved as an extension to the Church of England Cemetery.[18] It was used for burials from 1911 onwards, mostly from the same families who were interred in the older part of the cemetery. There were five burials there in 1911.[19]It became an integral part of the cemetery and is included as part of this listing.[1]

Monuments have been made by a variety of masons including a noted local mason, George Robertson of Windsor.[1]

The trustees handed over control of Wilberforce cemetery to Colo Shire Council on 27 February 1968.[20] It was closed for new burials in November 1986, though pre-existing rights to burial mean that there are occasionally additional interments.[21] It is now under the control of Hawkesbury Shire Council.[1]

In 2003, Cathy McHardy collated the total number of interments as 1,317, the number of monuments as 460 and the number of marked interments as 842.[22] She has identified three burials from the First Fleet; ten from the Second Fleet and four from the Third Fleet.[23][1]

Description

_and_Elizabeth_(d._1822)_Everingham._Matthew_Everingham_arrived_First_Fleet_in_1788_%2C_noted_early_Hawkesbury_settler._(5055789b2).jpg)

The Wilberforce Cemetery, formerly known as the St John's Church of England Cemetery, began as a large rectangular plot divided into four sections by a northeast–southwest path and a northwest–southeast path. The alignment of these paths remains clear, although the paths are now grassed over. The northwest–southeast path does not continue southeast beyond its junction with the northeast–southwest path. The northeast–southwest path also does not extend far southwest of the northwest–southeast path. The cemetery has some terracing along the edge of the northeast–southwest path to accommodate the slope across the site.[1]

The graves are laid out in approximate rows running northwest–southeast so that the graves can face approximately east. The alignment of the rows has been modified by the c. 1911 addition of a wedge-shaped section of land on the northeast side of the area and by the practicalities of aligning graves with the contours of the slope. Apart from the newer area of graves at the southwestern end of the eastern sector, the rows are irregular. This is probably as much to do with gravediggers coping with the slope of the land as with the apparently haphazard allocation of gravesites in the nineteenth century.[1]

.jpg)

The earliest burials are scattered around the cemetery although there is a definite preference to using the higher ground on the northwestern and northeastern sides. The addition of land c.1911 was followed by burials at the high land in that area. Even by the mid twentieth century, burials appear to be concentrated on the higher land on the northeastern and northwestern sides. New rows from the mid to late twentieth century are differentiated from the nineteenth and early twentieth century burials by the more ordered layout of the rows.[1]

There is no formal planting within the former St John's Church of England Cemetery. It has been left simply grassed with trees in the Clergy Road and Copeland Road reserves providing some separation between the cemetery and the surrounding town.[1]

- Fencing

An aluminium spear picket fence marks the boundary of the former St John's Church of England Cemetery. Gates are located on the northeast and southeast sides, aligning with the main axial paths.[1]

- Monuments

Wilberforce Cemetery contains a range of monument styles from the early nineteenth century to the late twentieth century. The majority of early monuments are upright slabs or grave markers. Sandstone is the most common material for the grave markers followed by white marble. Most monuments from the inter-war period onwards are slab and desk style, often built of granite.[1]

.jpg)

The cemetery is notable for the survival of a number of fine altar style slabs, although the condition of these vary. A rare table style slab monument for Emily, Eliza and Emily Louisa Robinson (died 1849, 1894 and 1928) also survives.[1]

- Columbaria

A pair of brick columbarium walls was built at the eastern entrance to the cemetery in the 1970s. They are simple cream brick walls with brick capping. The side of one wall has a plaque commemorating members of the First Fleet who lived in the area and were buried in the cemetery.[1]

- Condition

As at 12 March 2010, many of the monuments are in reasonable condition considering their age and problems in more recent years with vandalism. This is a reflection of the care and respect they have received from the local community. Some monuments have weathered so that their original inscriptions are no longer clear or have been lost. A number of these have had plaques fixed with the words of the original inscription repeated. Others have been re-engraved or have had the lettering blacked to make it clearer.[1]

The monuments in the worst condition are generally the table style slab monuments. Subsidence due to erosion on the steep site and/or inadequate footings for the original monument has contributed to this.[1]

Since Wilberforce Cemetery is an old and largely intact cemetery, the graves provide significant potential archaeological information about early burials and burial practices.[1]

Wilberforce Cemetery has a high degree of intactness. Numerous original early grave markers survive, often in reasonable condition. Though the cemetery had an additional area included on its eastern boundary, the layout of the oldest part of the cemetery is still apparent.[1]

Heritage listing

.jpg)

It is of State heritage significance because Wilberforce Cemetery is one of the five cemeteries established as part of the core functions of the five towns founded by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810. Wilberforce Cemetery demonstrates Macquarie's policy of ending the burial of deceased persons on their landholdings by establishing consecrated burial grounds in each of the towns he established. The cemetery contains a significant proportion of burials of convicts from the First, Second and Third Fleets. Of the burials at Wilberforce from 1811 to 1825, 36% were interments of convicts who arrived before 1800. Between 1811 and 1825, there was a considerable number of burials in the cemetery who were early ex-convict arrivals. Many were later joined by their families and descendants in the cemetery. A high number of older grave markers also survive, many of them for ex-convicts who arrived in the earlier period. Of all Macquarie's cemeteries, Wilberforce has the most interments with the highest proportional representation of ex-convict settlers from the First to the Third Fleets. Wilberforce is the only town of those founded by Macquarie which still retains the original buildings and burial ground at its centre. The visual inter-relationship of these elements is still apparent, as is the commanding position of the group on an elevated site.[1]

Many of the people interred in the cemetery founded families that continued to live in the area. Since Wilberforce was one of the original "hearth" areas of the colony from where settlers fanned out to settle other districts, Wilberforce Cemetery has significance for settlers across a broad expanse of the state.[1]

Many examples of altar style slab burial markers and a rare table slab monument remain within the cemetery. Wilberforce Cemetery is of State significance under this criterion.[1]

In conjunction with the schoolhouse-cum-chapel the cemetery has a strong ability to demonstrate Governor Lachlan Macquarie's vision for these towns.[1]

Wilberforce Cemetery was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 20 August 2010 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance because Wilberforce Cemetery is one of the five cemeteries established as part of the core functions of the five Hawkesbury towns founded by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810 as well as Liverpool on Georges River. Wilberforce Cemetery demonstrates Macquarie's policy of ending the burial of deceased persons on their landholdings by establishing consecrated burial grounds in each of the towns he established. The cemetery contains a significant proportion of burials of convicts from the First, Second and Third Fleets. Between 1811 and 1825, there was a considerable number of burials in the cemetery who were early ex-convict arrivals. Many were later joined by their families and descendants in the cemetery. A high number of older grave markers also survive, many of them for ex-convicts who arrived in the earlier period. Of all Macquarie's cemeteries, Wilberforce has the most interments with the highest proportional representation of ex-convict settlers from the First to the Third Fleets. Windsor has more convict burials but they arrived later. Richmond cemetery is dominated by free arrivals. The original Pitt Town cemetery does not exist any more. Castlereagh cemetery was largely unused. Liverpool cemetery has been destroyed. Of the burials at Wilberforce from 1811 to 1825, 36% were interments of convicts who arrived before 1800. A total of over 70 people who arrived before 1800 are buried there and a number of original gravestones or markers remain from the early period. The earliest one dates from February 1816. Wilberforce Cemetery has exceptional significance for the State of NSW and for Australia.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

It meets this criterion of State significance because it was one of the five cemeteries founded by Governor Lachlan Macquarie as one of the core functions of the five Hawkesbury towns he established in 1810 and has a strong association with him. Wilberforce Cemetery demonstrates Macquarie's policy of ending the burial of deceased persons on their landholdings by establishing consecrated burial grounds in each of the towns he established. It contains a considerable number of interments of convicts who arrived before 1800. Many of them founded families who continued to live in the area. Additionally, since Wilberforce was one of the original "hearth" areas of the colony from where settlers fanned out to settle other districts, the Wilberforce Cemetery has significance for settlers across a broad expanse of the state. Wilberforce Cemetery has high significance for the state of NSW and for the nation under this criterion.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance because Wilberforce Cemetery was an integral part of Governor Macquarie's scheme of creating towns with distinctive core functions aimed at improving the morality and social practices of the convict and ex-convict population. The towns he established had a church and school coupled with a burial ground at their core often in a commanding position. Wilberforce is the only town of those established by Macquarie which still retains the original buildings and burial ground at its centre. The visual inter-relationship of these elements is still apparent, as is the commanding position of the group on an elevated site.[1]

Positioned on a site personally selected by Macquarie during his visit, the cemetery is a significant landmark in Wilberforce particularly when viewed from the west and it punctuates the town with Macquarie's vision.[1]

Wilberforce Cemetery contains a remarkable collection of monuments from the early nineteenth century to the present day. Many styles of monuments survive including a fine collection of altar style slab monuments and a rare example of a table style slab monument. The work of one of the finest local masons, George Robertson of Windsor, is well represented in the cemetery. Wilberforce Cemetery is of State significance under this criterion.[1]

The place has strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

It meets this criterion of State significance because Wilberforce Cemetery has been a focus for the Wilberforce community since the 1810s. The original ex-convicts who were interred in the cemetery were joined by later generations of their families up to the present day. Later settlers have been interred there as well, so that the cemetery reflects the community. Additionally, since Wilberforce was one of the original "hearth" areas of the colony from where settlers fanned out to settle other districts, the Wilberforce Cemetery has significance for settlers across a broad expanse of the state. Hence, the Cemetery has become a place of pilgrimage for descendants from across the state and beyond, as well as being a focus for family reunions. Wilberforce Cemetery has high significance for the state of NSW under this criterion.[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance because Wilberforce Cemetery has been a focus for the Wilberforce community since the 1810s. The original ex-convicts who were interred in the cemetery were joined by later generations of their families up to the present day. Later settlers have been interred there as well, so that the cemetery reflects the community. Additionally, as one of the original "hearth" areas of the colony from where settlers fanned out to settle other districts, the Wilberforce Cemetery has significance for settlers across a broad expanse of the state. The monuments in Wilberforce Cemetery provide data for the study of the local community and for family history. The graves themselves provide potential archaeological information about early burials and burial practices, which would become apparent in any geophysical survey.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance because Wilberforce Cemetery is the only surviving example of the towns that Lachlan Macquarie created where the schoolhouse-cum-chapel and cemetery remain. They have a strong ability to demonstrate Governor Lachlan Macquarie's vision for these towns.[1]

Many examples of altar style slab burial markers and a rare table slab monument remain within the cemetery. Wilberforce Cemetery is of State significance under this criterion.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance because as the sole surviving example of Lachlan Macquarie's town centres which combined a schoolhouse-cum-chapel and cemetery it demonstrates the philosophy implicit in his town planning layouts. Wilberforce Cemetery has a strong ability to demonstrate Governor Lachlan Macquarie's vision for these towns.[1]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wilberforce Cemetery. |

- "Wilberforce Cemetery". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01837. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 17

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 18

- Field Book 67, p 45, SRNSW SZ 888

- Col Sec, Letters Sent, 1810, SRNSW 4/3490D, p 97

- (Sydney Gazette, 18 May 1811, p 1)

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 21

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 22

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 24

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 29

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 26-9

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 41

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 42

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 55

- SR Map 5960; W Baker, Map of the County of Cook, W Baker, Sydney, 1843-6

- (Ms.1262.3000, Crown Plan)

- NSWGG, 4 July 1896, p 4572

- (Ms.1262.3000, Crown Plan)

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 2, 38

- C McHardy, Sacred to the Memory, 4

- Hubert, Conservation Plan, 48

- C McHardy, Sacred to the Memory, 6

- C McHardy, Sacred to the Memory, 10

Bibliography

- Historical Records of NSW.

- Barkley, J & Nichols, M (1994). Hawkesbury 1794 - 1994.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hubert Architects & Ian Jack Heritage Consulting Pty Ltd (2008). "Wilberforce Cemetery Conservation Management Plan, Final Report, 2 vols".

- Kohen, J (1993). The Darug and their neighbours.

- Mchardy, C (2003). Sacred to the Memory: a study of Wilberforce Cemetery.

Attribution

![]()