Whirlpool

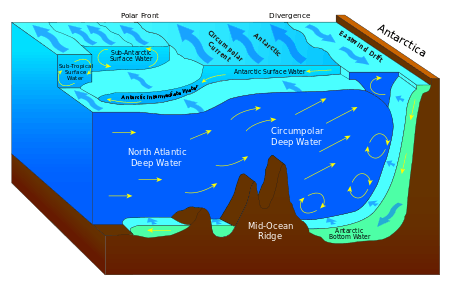

A whirlpool is a body of rotating water produced by opposing currents or a current running into an obstacle. Small whirlpools form when a bath or a sink is draining. More powerful ones in seas or oceans may be termed maelstroms. Vortex is the proper term for a whirlpool that has a downdraft.

In narrow ocean straits with fast flowing water, whirlpools are often caused by tides. Many stories tell of ships being sucked into a maelstrom, although only smaller craft are actually in danger.[1] Smaller whirlpools appear at river rapids[2] and can be observed downstream of artificial structures such as weirs and dams. Large cataracts, such as Niagara Falls, produce strong whirlpools.

Notable whirlpools

Saltstraumen

The Maelstrom of Saltstraumen is earth's strongest Maelstrom. It is located close to the Arctic Circle,[3] 33 km (20 mi) round the bay on Highway 17, south-east of the city of Bodø, Norway. The strait at its narrowest is 150 m (490 ft) in width and water "funnels" through the channel four times a day.[4] It is estimated that 400 million cubic metres (110 billion US gallons) of water passes the narrow strait during this event.[5] The water is creamy in colour and most turbulent during high tide. It is often witnessed by tourists.[4] It reaches speeds of 40 km/h (25 mph)[6]. As navigation is dangerous in this strait only a short segment of time is available for large ships to pass through.[3] Its impressive strength is caused by the world's strongest tide occurring in the same location during the new and full moon. A narrow channel of 3 km (2 mi) length connects the outer Saltfjord with its extension, the large Skjerstadfjord, causing a colossal tide which produces the Saltstraumen maelstrom.[7]

Moskstraumen

Moskstraumen or Moske-stroom is an unusual system of whirlpools in the open seas in the Lofoten Islands off the Norwegian coast.[8] It is the second strongest whirlpool in the world with flow currents reaching speeds as high as 32 km/h (20 mph).[3] This is supposedly the whirlpool depicted in Olaus Magnus' map, labeled as "Horrenda Caribdis" (Charybdis).[9]

The Moskstraumen is formed by the combination of powerful semi-diurnal tides and the unusual shape of the seabed, with a shallow ridge between the Moskenesøya and Værøy islands which amplifies and whirls the tidal currents.[6]

The fictional depictions of the Maelstrom by Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, and Cixin Liu describe it as a gigantic circular vortex that reaches the bottom of the ocean, when in fact it is a set of currents and crosscurrents with a rate of 18 km/h (11 mph).[10] Poe described this phenomenon in his short story A Descent into the Maelstrom, which during 1841 was the first to use the word "maelstrom" in the English language;[6] in this story related to the Lofoten Maelstrom, two fishermen are swallowed by the maelstrom while one survives.[11]

Corryvreckan

The Corryvreckan is a narrow strait between the islands of Jura and Scarba, in Argyll and Bute, on the northern side of the Gulf of Corryvreckan, Scotland. It is the third-largest whirlpool in the world.[3] Flood tides and inflow from the Firth of Lorne to the west can drive the waters of Corryvreckan to waves of more than 9 metres (30 ft), and the roar of the resulting maelstrom, which reaches speeds of 18 km/h (11 mph), can be heard 16 km (10 mi) away. Though it was classified initially as non-navigable by the Royal Navy it was later categorized as "extremely dangerous".[3]

A documentary team from Scottish independent producers Northlight Productions once threw a mannequin into the Corryvreckan ("the Hag") with a life jacket and depth gauge. The mannequin was swallowed and spat up far down current with a depth gauge reading of 262 m (860 ft) with evidence of being dragged along the bottom for a great distance.[12]

Other notable maelstroms and whirlpools

Old Sow whirlpool is located between Deer Island, New Brunswick, Canada, and Moose Island, Eastport, Maine, USA. It is given the epithet "pig-like" as it makes a screeching noise when the vortex is at its full fury and reaches speeds of as much as 27.6 km/h (17.1 mph).[6] The smaller whirlpools around this Old Sow are known as "Piglets".[3]

The Naruto whirlpools are located in the Naruto Strait near Awaji Island in Japan, which have speeds of 26 km/h (16 mph).[6]

Skookumchuck Narrows is a tidal rapids that develops whirlpools, on the Sunshine Coast, Canada with current speeds exceeding 30 km/h (19 mph).[6]

French Pass (Te Aumiti) is a narrow and treacherous stretch of water that separates D'Urville Island from the north end of the South Island of New Zealand. During 2000 a whirlpool there caught student divers, resulting in fatalities.[13]

A short-lived whirlpool sucked in a portion of the 1300 acre (~530 hectares) Lake Peigneur in Louisiana, United States after a drilling mishap on 20 November 1980. This was not a naturally occurring whirlpool, but a disaster caused by underwater drillers breaking through the roof of a salt mine. The lake then drained into the mine until the mine filled and the water levels equalized, but the formerly-ten-foot deep lake was now 1,300 feet deep. This mishap resulted in destruction of five houses, loss of nineteen barges and eight tug boats, oil rigs, a mobile home, trees, acres of land, and most of a botanical garden. The adjacent settlement of Jefferson Island was reduced in area by 10%. A crater 0.5-mile (~1km) across was left behind. Nine of the barges which had sunk floated back.[14][15][16]

A more recent example of an artificial whirlpool that received significant media coverage occurred during early June 2015, when an intake vortex formed in Lake Texoma, on the Oklahoma–Texas border, near the floodgates of the dam that forms the lake. At the time of the whirlpool's formation, the lake was being drained after reaching its highest level ever. The Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dam and lake, expected that the whirlpool would last until the lake reached normal seasonal levels by late July.[17]

Dangers

Powerful whirlpools have killed unlucky seafarers, but their power tends to be exaggerated by laymen.[18] One of the few reports of large ships ever being sucked into a whirlpool is from the fourteenth century Mali Empire ruler Mansa Musa, as reported by a contemporary, Al-Umari[19]:

The ruler who preceded me did not believe that it was impossible to reach the extremity of the ocean that encircles the earth (meaning Atlantic), and wanted to reach that (end) and obstinately persisted in the design. So he equipped two hundred boats full of men, like many others full of gold, water and victuals sufficient enough for several years. He ordered the chief (admiral) not to return until they had reached the extremity of the ocean, or if they had exhausted the provisions and the water. They set out. Their absence extended over a long period, and, at last, only one boat returned. On our questioning, the captain said: 'Prince, we have navigated for a long time, until we saw in the midst of the ocean as if a big river was flowing violently. My boat was the last one; others were ahead of me. As soon as any of them reached this place, it drowned in the whirlpool and never came out. I sailed backwards to escape this current.'[20]

Tales like those by Paul the Deacon, Edgar Allan Poe, and Jules Verne are entirely fictional.[21]

However, temporary whirlpools caused by major engineering disasters can submerge large ships, like the Lake Peigneur disaster described above.

In literature and popular culture

Besides Poe and Verne, another literary source is of the 1500s, Olaus Magnus, a Swedish bishop, who had stated that a maelstrom more powerful than the one written about in The Odyssey sucked in ships which sank to the bottom of the sea, and even whales were pulled in. Pytheas, the Greek historian, also mentioned that maelstroms swallowed ships and threw them up again.

The monster Charybdis of Greek mythology was later rationalized as a whirlpool, which sucked entire ships into its fold in the narrow coast of Sicily, a disaster faced by navigators.[22]

During the 8th century, Paul the Deacon, who had lived among the Belgii, described tidal bores and the maelstrom for a Mediterranean audience unused to such violent tidal surges:[23]

Not very far from this shore … toward the western side, on which the ocean main lies open without end, is that very deep whirlpool of waters which we call by its familiar name "the navel of the sea." This is said to suck in the waves and spew them forth again twice every day. … They say there is another whirlpool of this kind between the island of Britain and the province of Galicia, and with this fact the coasts of the Seine region and of Aquitaine agree, for they are filled twice a day with such sudden inundations that any one who may by chance be found only a little inward from the shore can hardly get away. I have heard a certain high nobleman of the Gauls relating that a number of ships, shattered at first by a tempest, were afterwards devoured by this same Charybdis. And when one only out of all the men who had been in these ships, still breathing, swam over the waves, while the rest were dying, he came, swept by the force of the receding waters, up to the edge of that most frightful abyss. And when now he beheld yawning before him the deep chaos whose end he could not see, and half dead from very fear, expected to be hurled into it, suddenly in a way that he could not have hoped he was cast upon a certain rock and sat him down.

— Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards, i.6

Three of the most notable literary references to the Lofoten Maelstrom date from the nineteenth century. The first is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe named "A Descent into the Maelström" (1841). The second is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870), a novel by Jules Verne. At the end of this novel, Captain Nemo seems to commit suicide, sending his Nautilus submarine into the Maelstrom (although in Verne's sequel Nemo and the Nautilus were seen to have survived). The "Norway maelstrom" is also mentioned in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.[24]

In the 'Life of St Columba', the author, Adomnan of Iona', attributes to the saint miraculous knowledge of a particular bishop who sailed into a whirlpool off the coast of Ireland. In Adomnan's narrative, he quotes Columba saying[25]

Cólman mac Beognai has set sail to come here, and is now in great danger in the surging tides of the whirlpool of Corryvreckan. Sitting in the prow, he lifts up his hands to heaven and blesses the turbulent, terrible seas. Yet the Lord terrifies him in this way, not so that the ship in which he sits should be overwhelmed and wrecked by the waves, but rather to rouse him to pray more fervently that he may sail through the peril and reach us here.

The Corryvreckan whirlpool plays a key role in the 1945 Powell-Pressburger film I Know Where I'm Going. Joan Webster (Wendy Hiller), is determined to get to the fictional Isle of Kiloran and marry her fiancé. Dangerous weather delays her crossing, and her determination becomes desperation when she realizes that she is falling in love with Torquil MacNeil (Roger Livesey). Against the advice of experienced folk, she offers a young fisherman a huge sum of money to take her over. At the last moment, Torquil steps into the boat, and after a squall knocks the engine out of commission, they face the whirlpool. Torquil manages to repair the engine before the tide turns, and they return to the mainland. This part of the picture uses footage Powell filmed at Corryvreckan (tied to a mast the leave both hands free for the camera) incorporated into scenes shot in a huge tank at the studio.[26]

In the movie Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End, the penultimate battle between The Black Pearl and The Flying Dutchman takes place with both ships sailing inside a giant whirlpool which appears to be over a kilometer wide and several hundred meters deep.

Etymology

One of the earliest uses in English of the Scandinavian word (malström or malstrøm) was by Edgar Allan Poe in his short story "A Descent into the Maelström" (1841). The Nordic word itself is derived from the Dutch word maelstrom, modern spelling maalstroom, from malen (to mill or to grind) and stroom (stream), to form the meaning grinding current or literally "mill-stream", in the sense of milling (grinding) grain.[27]

- Whirlpools

A whirlpool in a glass of water

A whirlpool in a glass of water

- A small whirlpool in Tionesta Creek in the Allegheny National Forest

A whirlpool in a small pond

A whirlpool in a small pond- Tide whirlpool in Rooi-Els, Western Cape

An artificial whirlpool in the Water Garden within Alnwick Garden

An artificial whirlpool in the Water Garden within Alnwick Garden

See also

- Coriolis effect

- Eddy (fluid dynamics)

- Rip current

References

- 10 Magnificent Maelstroms. WebEcoist. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Carreck, Rosalind, ed. (1982). The Family Encyclopedia of Natural History. The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 246. ISBN 0-7112-0225-7.

- Doyle, James (1 March 2012). A Young Scientist's Guide to Defying Disasters. Gibbs Smith. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4236-2441-7.

- Brown, Jules (2004). The Rough Guide to Barcelona. Rough Guides. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-84353-218-7. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Michelin Travel Publications (Firm) (2001). Scandinavia – Finland. Michelin Travel Publications. p. 201. ISBN 978-2-06-000140-1. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Compton, Nic (28 July 2013). Why Sailors Can't Swim and Other Marvellous Maritime Curiosities. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-4081-9263-4.

- "Saltstraumen" (in Norwegian). Store Norske Leksikon. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 1958 edition.

- Nigg, Joseph (2014), Sea Monsters: A Voyage around the World's Most Beguiling Map, University of Chicago Press, p. 122, ISBN 0-226-92518-8

- B. Gjevik, H. Moe and A Ommundseb, "Strong Topographic Enhancement of Tidal Currents: Tales of the Maelstrom", University of Oslo, working paper, 5 September 1997. A condensed version published as Gjevik, B.; Moe, H.; Ommundsen, A. (1997). "Sources of the Maelstrom" (PDF). Nature. 388 (6645): 837–838. doi:10.1038/42159. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 April 2004.

- James Kenney (19 December 2012). Thriving in the Crosscurrent: Clarity and Hope in a Time of Cultural Sea Change. Quest Books. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-8356-3019-1.

- "Equinox: Lethal Seas". Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2016. UK and US co-production by Northlight, "Lethal Seas" UK Channel 4, "Sea Twister!" US Discovery Channel, covers several notable maelstroms.

- Smith, I R (14 April 2003). "In the matter of an inquest into the deaths of Narelle Taniko te Purei, Ricki Graeme McDonald and Michael David Welsh" (PDF). Nelson District Coroner – via Dive New Zealand.

- Stephen Pile (4 October 2012). The Not Terribly Good Book of Heroic Failures: An intrepid selection from the original volumes. Faber & Faber. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-571-27734-6.

- Richard Heggen (16 January 2015). Underground Rivers: From the River Styx to the Rio San Buenaventura, with occasional diversions. Richard Heggen. pp. 1108–. GGKEY:BS7JB1BB957.

- "And away goes the lake down the drain!". Archive of tripod.com. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Smith, Chelsi (8 June 2015). "Levels at Lake Texoma decrease; rare look at intake vortex". Sherman, TX: KXII-TV. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- MythBusters Episode 56: Killer Whirlpool. Mythbustersresults.com. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Mohammed Hamidullah. "Echos of What Lies Behind the 'Ocean of Fogs' in Muslim Historical Narratives". Muslim Heritage. Retrieved 27 June 2015. (Quoting from Al-Umari 1927, q.v.)

- Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards (8th century AD); Edgar Allan Poe, "A Descent into the Maelström" (1841); and Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870).

- Andrews, Tamra (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. Oxford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-19-513677-7. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Deacon, Paul the (3 June 2011). History of the Lombards. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-8122-0558-8.

- Herman Melville Moby-Dick Chapter 36, Wikisource.

- Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin Books, 1995

- "I Know Where I'm Going (1945) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- The Merriam-Webster new book of word histories. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 1991. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-87779-603-9. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

Further reading

- Baron PA, Willeke K (1986) Respirable droplets from whirlpools: measurements of size distribution and estimation of disease potential. Environ Res 39, 8–18.

- Blake, John Lauris (1845). The Wonders of the Ocean. Henry & Sweetlands. pp. 50–53.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whirlpools. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Videos of whirlpools. |

| Look up whirlpool in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |