Western trumpeter whiting

The western trumpeter whiting, Sillago burrus, is a species of marine fish of the smelt whiting family Sillaginidae that is commonly found along the northern coast of Australia and in southern Indonesia and New Guinea. As its name suggests, it is closely related to and resembles the trumpeter whiting which inhabits the east coast of Australia and is distinguishable by swim bladder morphology alone. The species inhabits a variety of sandy, silty and muddy substrates in depths from 0 to 15 m deep, with older fish inhabiting deeper waters. Western trumpeter whiting are benthic carnivores which take predominantly crustaceans and polychaetes as prey. The species reaches sexual maturity at the end of its first year of age, spawning in batches between December and February The species is taken as bycatch with other species of whiting and shrimps in Australia.

| Western trumpeter whiting | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Sillaginidae |

| Genus: | Sillago |

| Species: | S. burrus |

| Binomial name | |

| Sillago burrus Richardson, 1842 | |

| |

| Range of the western trumpeter whiting | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy and naming

The western trumpeter whiting is one of 29 species in the genus Sillago, which is one of three divisions of the smelt whiting family Sillaginidae. The smelt-whitings are Perciformes in the suborder Percoidea.[1]

The species was first recorded by Lieutenant Emery of HMS Beagle during the Australian leg of its voyage, with Emery making a detailed sketch of the fish. This sketch and description was received by John Richardson in 1842, from which he described and named the species Sillago burrus without designating a holotype specimen, and furthermore the original sketch has apparently been lost. The location where the specimen was taken is also uncertain, with McKay narrowing down the range to between Depuch and Barrow Islands in northern Western Australia, with New Guinea an outside possibility. In 1985 McKay designated a neotype from the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia.[2]

The species has only ever been assigned one synonym, S. maculata burrus by Whitley in 1948 with apparently no reason given for the reassignment, although McKay also treated the species as a subspecies of S. maculata in his comprehensive revision of the Sillaginidae.[3]

Description

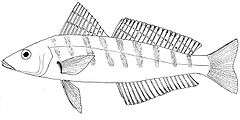

As with most of the genus Sillago, the western trumpeter whiting has a slightly compressed, elongate body tapering toward the terminal mouth, reaching a maximum overall length of 36 cm (14 in).[1] The body is covered in small ctenoid scales extending to the cheek and head. The first dorsal fin has 11 spines and the second dorsal fin has 1 leading spine with 19 to 21 soft rays posterior. The anal fin is similar to the second dorsal fin, but has 2 spines with 18 to 20 soft rays posterior to the spines. Other distinguishing features include 69 to 76 lateral line scales and a total of 34 to 36 vertebrae.[3]

Swim bladder morphology is the most effective way to distinguish it between related species S. maculata and S. aeolus. The swim bladder has far reduced anterolateral extensions of swim bladder compared to S. maculata and differs from S. aeolus in having two extensions, not three.[2]

The western trumpeter whiting has very similar in coloration to S. aeolus and S. maculata, with only minor differences between the species. The body is an overall light sandy brown, being darker above and paler on the lower sides, with a silver mid line of the belly. The darker and lighter regions of the body are separated by a dull silver longitudinal band positioned mid laterally on the side of the body. In S. burrus the blotches are like oblique bars and they are not joined as in S. maculata. There is an indistinct black spot at the base of the pectoral fin and the upper and lower margins of the caudal fin are not as dark as in S. maculata. The abdominal walls are usually white or silvery, where they are pale flesh coloured in the other trumpeter whitings.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The western trumpeter whiting ranges from southern Western Australia[4] northwards along the coast of the Northern Territory and north Queensland as well as further north along southern Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

S. burrus inhabits water between 5 and 15 m deep, with juveniles inhabiting shallow shoreline areas and moving offshore to slightly deeper water as they mature. They do not extend to the depths of other co-occurring sillaginids such as S. robusta.[5] S. burrus prefers silty-sand or muddy substrates, with the larger adults feeding near channels and sandbars, and may also be found on mostly sandy bottoms.[3]

The juveniles of the species are known to inhabit protected seagrass beds where they take advantage both the sheltered environment and also prey species that inhabit the seagrass community.[6] The young are also known to inhabit mangrove creeks and broken bottom,[3] as well as entering estuaries during Summer and Autumn in southern estuaries. Juvenile S. burrus are recruited to the estuary system, where with a number of other species continue a cycle of fish species throughout the year.[7] The species also has the ability to withstand brackish water for extended periods, evident by their presence in intermittently open estuaries which are closed to the sea for most of the year.[8]

Biology

Diet

The western trumpeter whiting occupies the same areas a number of other sillaginids, and therefore has a slightly different diet to these other species to avoid interspecific competition. The predominant prey consists of crustaceans, with copepods and to a lesser extent amphipods and shrimp and other decapods the main types taken. Polychaetes are also a common part of the diet, with bivalves and echinoderms also contributing to its diet. The main difference in its diet is the high amount of copepods consumed, especially in juveniles.[9]

The diet of the western trumpeter whiting changes with age like many of its close relatives. During its juvenile stage, the species diet is predominantly grammarid amphipods and copepods, while as the fish grow to maturity, they tend to take more decapods such as caridean shrimps and crabs, as well as polychaetes.[6]

Life cycle

The western trumpeter whiting spawns predominantly between December and February, with a peak in January. During the spawning period, the ovaries possess large numbers of hydrated oocytes and no post-ovulatory follicles, with the oocytes tending to form several relatively discrete size groups. This indicates that S. burrus produces eggs in batches and that the spawning of the members of this species is synchronised.[10] The spreading of the release of eggs over the spawning periods would act as a buffer against any problems posed by adverse fluctuations in environmental conditions such as the amount of food available to larvae, or to predation pressure.[11]

S. burrus becomes sexually mature between lengths of 130 to 139 mm (5.1 to 5.5 in) for females and 120 to 139 mm (4.7 to 5.5 in) for males, with this occurring normally by the end of the first year of life. Juveniles inhabit shallow protected waters, often in estuaries, mangroves or protected bays, remaining there for about three months before migrating to deeper waters between 5 and 15 m (16 and 49 ft) depth when they are around 70 mm (2.8 in) in length.[10] This may be to reduce competition with other inshore sillaginid species such as S. vittata and S. bassensis, whose juvenile stages occupy the same shallow areas as S. burrus.[12][13]

Relationship to humans

The western trumpeter whiting is commonly trawled in association with the western population of Sillago robusta, as well as Sillago lutea in depths up to 36 m (118 ft), with water between 5–15 m (16–49 ft) the most prolific. The juveniles are also part of the bycatch of shrimp trawlers, which sweep through the seagrass habitat of these juveniles.[3] In some areas such as the Leschenault Estuary in Western Australia, the western trumpeter whiting is a sought after fish by anglers, who catch it alongside other species of whiting.[4] The species is considered good eating, and is marketed fresh in Australia.[3]

References

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2007). "Sillago burrus" in FishBase. Aug 2007 version.

- McKay, R.J. (1985). "A Revision of the Fishes of the Family Silaginidae". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 22 (1): 1–73.

- McKay, R.J. (1992). FAO Species Catalogue: Vol. 14. Sillaginid Fishes Of The World. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation. pp. 19–20. ISBN 92-5-103123-1.

- Potter, I. C.; P. N. Chalmer; D. J. Tiivel; R. A. Steckis; M. E. Platell; R. C. J. Lenanton (December 2000). "The fish fauna and finfish fishery of the Leschenault Estuary in south-western Australia" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia. 83 (4): 481–501.

- Hyndes, G.A.; M. E. Platell; I. C. Potter; R. C. J. Lenanton (July 1999). "Does the composition of the demersal fish assemblages in temperate coastal waters change with depth and undergo consistent seasonal changes?". Marine Biology. 134 (2): 335–352. doi:10.1007/s002270050551.

- Kwak, Seok Nam; David W. Klumpp (February 2004). "Temporal variation in species composition and abundance of fish and decapods of a tropical seagrass bed in Cockle Bay, North Queensland, Australia". Aquatic Botany. 78 (2): 119–134. doi:10.1016/j.aquabot.2003.09.009.

- Kanandjembo, A.N.; I. C. Potter; M. E. Platell (2001). "Abrupt shifts in the fish community of the hydrologically variable upper estuary of the Swan River". Hydrological Processes. 15 (13): 2503–2517. doi:10.1002/hyp.295.

- Potter, I.C.; G.C. Young; G.A. Hyndes; S. de Lestang (1997). "The ichthyofauna of an intermittently open estuary: Implications of bar breaching and low salinities on faunal composition". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 45 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1006/ecss.1996.0165.

- Hyndes, G.A.; M. E. Platell; I. C. Potter (1997). "Relationships between diet and body size, mouth morphology, habitat and movements of six sillaginid species in coastal waters: implications for resource partitioning". Marine Biology. 128 (4): 585–598. doi:10.1007/s002270050125.

- Hyndes, G.A.; I. C. Potter; S. A. Hesp (September 1996). "Relationships between the movements, growth, age structures, and reproductive biology of the teleosts Sillago burrus and S. vittata in temperate marine waters". Marine Biology. 126 (3): 549–558. doi:10.1007/BF00354637.

- Lambert, T.C.; T.M. Ware (1984). "Reproductive strategies of demersal and pelagic spawning fish". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 41 (11): 1564–1569. doi:10.1139/f84-194.

- Hyndes, G.A.; I.C. Potter (1997). "Age, growth and reproduction of Sillago schomburgkii in south-western Australian, nearshore waters and comparisons of life history styles of a suite of Sillago species". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 49 (4): 435–447. doi:10.1023/A:1007357410143.

- Hyndes, G.A.; I.C. Potter (July 1996). "Comparisons between the age structures, growth and reproductive biology of two co-occurring sillaginids, Sillago robusta and S. bassensis, in temperate coastal waters of Australia". Journal of Fish Biology. 49 (1): 14–32. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1996.tb00002.x.