West-Harris House

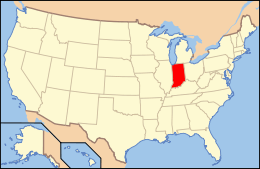

West-Harris House, also known as Ambassador House, is a historic home located at 106th Street and Eller Road in Fishers, Hamilton County, Indiana. The ell-shaped, two-story, Colonial Revival-style dwelling with a large attic and a central chimney also features a full-width, hip-roofed front porch and large Palladian windows on the gable ends of the home. It also includes portions of the original log cabin dating from ca. 1826, which was later enlarged and remodeled. In 1996 the home was moved to protect it from demolition about 3 miles (4.8 km) from its original site to its present-day location at Heritage Park at White River in Fishers. The former residence was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999 and is operated as a local history museum, community events center, and private rental facility.

West-Harris House | |

West-Harris House, January 2013 | |

| |

| Location | 10595 Eller Rd., Fishers, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°56′28″N 86°3′57″W |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Built | c. 1826, c. 1895 |

| Architect | Thomas West (original owner, 1826) |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 99000297[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 23, 1999 |

The restored home is named in honor of two of its previous owners, Thomas and Sarah West, and Addison and India Harris. The Wests had the original two-room log section of the home erected about 1826 on their land at the northwest corner of present-day 96th Street and Allisonville Road in Fishers. Addison Harris purchased the rural property in 1880 and had the home enlarged and remodeled around 1895. Harris was a prominent Indianapolis lawyer, a former member of the Indiana Senate (1876 to 1880), and a U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Austria-Hungary (1899 to 1901). His wife, India, was active in the Indianapolis arts community, serving from 1905 to 1907 as president of the Art Association of Indianapolis (the predecessor to the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Indiana University – Purdue University at Indianapolis's Herron School of Art and Design). The home's nickname of Ambassador House comes from Addison Harris's diplomatic service in Vienna, Austria, during President William McKinley's administration.

History

Thomas and Sarah West, early settlers of Hamilton County, Indiana, had the original, two-room log section of the home erected around 1826 on rural land they acquired on the northwest corner of present-day 96th Street and Allisonville Road in Fishers. William Hartman purchased the property from West family heirs in 1871 and acquired additional acreage to enlarge the farm.[2]

Addison C. Harris (1840–1916), a prominent Indianapolis lawyer and former member of the Indiana Senate (1876 to 1880), acquired the property in 1880 and had the home remodeled and enlarged around 1895. Harris and wife, India Crago Harris (1848–1948), used the home as a summer residence. Its nickname of Ambassador House relates to Addison Harris's diplomatic service (1899 to 1901) as U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Austria-Hungary during President William McKinley's administration.[3][4] India Harris was active in the Art Association of Indianapolis, the forerunner to the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis Herron School of Art and Design. She served for many years on its board of trustees, including leadership roles as recording secretary (1893–1899) and as its fifth president (1904–1907). She also established Herron's reference library and served as chair of its library committee.[5]

After the death of her husband in 1916, India Harris maintained the home until her death in 1948.[6] She bequeathed the property to Indiana University, who sold off portions of the land over a period of several years.[6]

The Washington Park Cemetery Association, a subsequent owner, acquired the home and 192 acres (78 hectares) of surrounding land in 1995. The cemetery association divided their property into three parcels, retaining one of them to enlarge a neighboring cemetery. The association donated another parcel to the Town (present-day City) of Fishers for a public park (which became Heritage Park at White River), and sold the third parcel, including the site of the West-Harris home, for commercial development.[7]

Preservation and restoration

In 1996 the Fishers town council and a group of local preservationists took action to save the historic home from demolition when plans were made to clear the surrounding land for commercial development. The Town (present-day City) of Fishers took possession of the house in 1996 and supervised its move to town-owned land at 106th Street and Eller Road, the site of Heritage Park at White River. The park is approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) from the home's original location at 96th Street and Allisonville Road. The home's pillars and stone outbuilding were donated to the Town of Fishers in 1997.[7][6]

Present-day use

Ambassador House, now fully restored, is operated as a local history museum and a site for community events and private rentals at Fishers Heritage Park at White River.[6][8]

Description

Exterior

The West-Harris house is an ell-shaped, two-story, Colonial Revival-style structure with a large attic and a central chimney. It features a full-width, hip-roofed front porch and large Palladian windows on the gable ends of the home.[9] :5

The original two-room log section (main portion of the single-family dwelling) was built about 1826. It was enlarged about 1895. Additions to the home included a stair hall, a two-story rear kitchen ell, a rear porch, and an attic. Renovations used post-and-beam construction in the original section of the home and wood-frame construction for the additions. The original log exterior was covered in wood siding during renovations and its interior was covered in plaster. The structure rests on a brick foundation and has a shingle roof (original shake shingles were later replaced with asphalt shingles.)[9] Two rooms of the home retain the original log construction, ca. 1826. Original logs are visible from the basement level of the home.[7]

The main facade to the south is two-and-a-half stories high. The first floor includes a central door with double-hung sash windows flanking each side. The second-floor sash windows are installed above the first-floor windows. The attic has two dormer windows. The home's corners have simple, classically inspired pilasters that are fluted at the second level. The west facade's notable features include a large Palladian window on the gable end of the main house. The east facade is similar to the west facade with the exception of a large bay window that has been added. The north facade has a centered door on the first floor of the main structure with a window centered above it on the second floor. Its gable end has three windows, one on the first and two on the second floor. A one-story porch, possibly a screened sleeping porch, was removed sometime after 1895.[9]

Interior

The main portion of the home includes two rooms on each floor surrounding a central chimney. A stair hall constructed across the north side of the home provides access on the west end to the kitchen ell and the basement beneath it. A door on the east end of hall leads to a rear porch. The front rooms of the home's main section and two small rooms over the kitchen ell also connect to the stair hall. The second level has two bedrooms, with two bathrooms built at each end of the stair hall. Access to the attic is through pull-down stairs in the hallway.[10]

The kitchen ell contains a large work area and a small room adjacent to the kitchen on the first floor. The second floor contains two small rooms.[10]

Outbuilding

A one-story rectangular outbuilding that is believed to have served as an ice house and/or summer kitchen is constructed of rubble stone masonry and has a simple gable roof.[10]

National register nomination

Although moved buildings are not typically eligible for a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the application made in 1999 requested an exception to be made for this structure. The major reasons cited for the exception request was due to Addison and India Harris's ownership of the home. There are no other extant structures related to them during the time they were most prominent in Indianapolis and the home's move was necessary to protect it from demolition at its original site.[11] The West-Harris home was listed on the National Register in 1999.[1]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved October 10, 2018. Note: This includes Ann Milkovitch McKee and Carol Ann Schweikert (March 26, 1997). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: West-Harris House" (PDF). p. Section 8, p. 4. Retrieved October 10, 2018. and Accompanying photographs.

- Leander J. Monks, Logan Esarey, and Ernest V. Shockley (1916). Courts and Lawyers of Indiana. 3. Indianapolis: Federal Publishing Company. pp. 1306–07. OCLC 4158945.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Addison Harris: Indianapolis Man Receives Appointment as Ambassador". Muncie Morning News. 21 (220). January 11, 1899. p. 1. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- Anne P. Robinson and S. B. Berry (2008). Every Way Possible: 125 Years of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 19–23, 27, 295. ISBN 9780936260853.

- John Tuohy (July 26, 2007). "Progress being made on Ambassador House" (PDF). Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: West-Harris House," Section 8, p. 5.

- "Fishers Heritage Park at White River". City of Fishers, Indiana. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: West-Harris House," Section 7, p. 1.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: West-Harris House, " Section 7, pp 2–3.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: West-Harris House, " Section 8, p. 6.