Well dressing

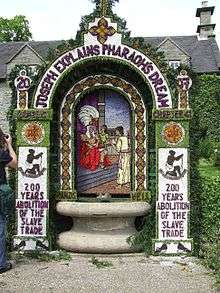

Well dressing, also known as well flowering, is a tradition practised in some parts of rural England in which wells, springs and other water sources are decorated with designs created from flower petals.[1] The custom is most closely associated with the Peak District of Derbyshire and Staffordshire.[2] James Murray Mackinlay, writing in 1893, noted that the tradition was not observed in Scotland; W. S. Cordner, in 1946, similarly noted its absence in Ireland.[3][4] Both Scotland and Ireland do have a long history of the veneration of wells, however, dating from at least the 6th century.[5][6]

The custom of well dressing in its present form probably began in the late 18th century, and evolved from "the more widespread, but less picturesque" decoration of wells with ribbons and simple floral garlands.[7][8]

History

The location identified most closely with well dressing is Tissington, Derbyshire, though the origins of the tradition are obscure. It has been speculated that it began as a pagan custom of offering thanks to gods for a reliable water supply; other suggested explanations include villagers celebrating the purity of their water supply after surviving the Black Death in 1348, or alternatively celebrating their water's constancy during a prolonged drought in 1615.[9] The practice of well dressing using clay boards at Tissington is not recorded before 1818, however, and the earliest record for the wells being adorned by simple garlands occurs in 1758.[10]

Well dressing was celebrated in at least 12 villages in Derbyshire by the late 19th century, and was introduced in Buxton in 1840, "to commemorate the beneficence of the Duke of Devonshire who, at his own expense, made arrangements for supplying the Upper Town, which had been much inconvenienced by the distance to St Anne's well on the Wye, with a fountain of excellent water within easy reach of all".[11][12] Similarly, well dressing was revived at this time in Youlgreave, to celebrate the supplying of water to the village "from a hill at some distance, by means of pipes laid under the stream of an intervening valley.".[13] With the arrival of piped water the tradition was adapted to include public taps, although the resulting creations were still described as well dressings.

The custom waxed and waned over the years, but has seen revivals in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, South Yorkshire, Cheshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire and Kent.[14][15]

Process

Wooden frames are constructed and covered with clay, mixed with water and salt. A design is sketched on paper, often of a religious theme, and this is traced onto the clay. The picture is then filled in with natural materials, predominantly flower petals and mosses, but also beans, seeds and small cones. Each group uses its own technique, with some areas mandating that only natural materials be used while others feel free to use modern materials to simplify production. Wirksworth and Barlow are two of the very few dressings where the strict use of only natural materials is still observed.

In literature

John Brunner's story "In the Season of the Dressing of the Wells" describes the revival of the custom in an English village of the West Country after World War I and its connection to the Goddess.[16][17]

Jon McGregor's novel Reservoir 13 is set in a village where well dressing is an annual event.[18]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Ditchfield 1896, p. 186

- Ditchfield 1896, p. 184, 186, 188

- Mackinlay 1893, p. 206, 212

- Cordner 1946, p. 33

- Cordner 1946, p. 25-26

- Moore & Terry 1894, pp. 215–216

- Jewitt 1863, p. 40

- Simpson & Roud 2000, p. 385

- Christian 1976, pp. 206–7

- Shirley 2017, p. 653

- Norman 1993, p. 138

- "Buxton well dressing of 1856". The Derby Mercury. Derby. 28 April 1858.

- "Well dressing". The Derby Mercury. Derby. 10 August 1842.

- "Malvern Well Dressing History", Malvern Spa Association, archived from the original on 4 August 2012, retrieved 12 July 2010

- "The History of Well Dressing", Hargate Hall, 2008, retrieved 20 April 2010

- "After the King". Tolkien Gateway. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- Martin H. Greenberg, ed. (1992). After the King: Stories In Honor of J.R.R. Tolkien. New York: Tor. pp. 106–150. ISBN 0312851758. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- Hadley, Tessa (15 April 2017). "Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor review – a chilling meditation on loss and time". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Christian, Roy (1976). The Peak District. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7094-4.

- Cordner, W.S. (1946), "The Cult of the Holy Well", Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 9: 24–36

- Ditchfield, Peter Hampson (1896), Old English Customs Extant at the Present Time, London: George Redway

- Jewitt, Llewellynn (1863), "Some Additional Notes on the Tissington Well Dressing", The Reliquary and Illustrated Archæologist, London: John Russell Smith, pp. 37–48

- Moore, A. W.; Terry, John F. (1894), "Water and Well-Worship in Man", Folklore, 5 (3): 212–229, doi:10.1080/0015587X.1894.9720224

- Mackinlay, James Murray (1893), "Offerings at Lochs and Springs", Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, Glasgow: William Hodge & Co.

- Norman, Charlotte A. (1993), "'Annual Well Dressing—Another Brilliant Success—Finest Work For Many Years' (By Our Own Correspondent)'", in Buckland, Theresa; Wood, Juliette (eds.), Aspects of British Calendar Customs, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 137–146, ISBN 1850752435

- Shirley, Rosemary (2017), "Festive landscapes: the contemporary practice of well-dressing in Tissington" (PDF), Landscape Research, 42 (6): 650–662, doi:10.1080/01426397.2017.1317725

- Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000), A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-192-10019-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Well dressing. |

- welldressing.com Listing of dates and sites, with galleries of photos and historical information

- Official website for the Stoney Middleton Well Dressing Committee

- Official website of the Buxton Wells Dressing Festival

- Short history of well dressing

- Tissington Hall's guide to producing welldressings

- Well dressings in Wirksworth Derbyshire Archived 5 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Community site for Wirksworth Derbyshire

- Well Dressings in Barlow, Derbyshire. Dressed year on year for at least 150 years

- A history of well dressing in Wormhill

- Well dressings in Brackenfield