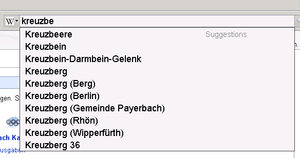

Web search query

A web search query is a query based on a specific search term that a user enters into a web search engine to satisfy their information needs. Web search queries are distinctive in that they are often plain text or hypertext with optional search-directives (such as "and"/"or" with "-" to exclude). They vary greatly from standard query languages, which are governed by strict syntax rules as command languages with keyword or positional parameters.

Types

There are three broad categories that cover most web search queries: informational, navigational, and transactional.[1] These are also called "do, know, go."[2] Although this model of searching was not theoretically derived, the classification has been empirically validated with actual search engine queries.[3]

- Informational queries – Queries that cover a broad topic (e.g., colorado or trucks) for which there may be thousands of relevant results.

- Navigational queries – Queries that seek a single website or web page of a single entity (e.g., youtube or delta air lines).

- Transactional queries – Queries that reflect the intent of the user to perform a particular action, like purchasing a car or downloading a screen saver.

Search engines often support a fourth type of query that is used far less frequently:

- Connectivity queries – Queries that report on the connectivity of the indexed web graph (e.g., Which links point to this URL?, and How many pages are indexed from this domain name?).[4]

Characteristics

Most commercial web search engines do not disclose their search logs, so information about what users are searching for on the Web is difficult to come by.[5] Nevertheless, research studies appeared in 1998.[6][7] Later, a study in 2001[8] analyzed the queries from the Excite search engine showed some interesting characteristics of web search:

- The average length of a search query was 2.4 terms.

- About half of the users entered a single query while a little less than a third of users entered three or more unique queries.

- Close to half of the users examined only the first one or two pages of results (10 results per page).

- Less than 5% of users used advanced search features (e.g., boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT).

- The top four most frequently used terms were, (empty search), and, of, and sex.

A study of the same Excite query logs revealed that 19% of the queries contained a geographic term (e.g., place names, zip codes, geographic features, etc.).[9] Studies also show that, in addition to short queries (i.e., queries with few terms), there are also predictable patterns to how users change their queries.[10]

A 2005 study of Yahoo's query logs revealed 33% of the queries from the same user were repeat queries and that 87% of the time the user would click on the same result.[11] This suggests that many users use repeat queries to revisit or re-find information. This analysis is confirmed by a Bing search engine blog post telling about 30% queries are navigational queries [12]

In addition, much research has shown that query term frequency distributions conform to the power law, or long tail distribution curves. That is, a small portion of the terms observed in a large query log (e.g. > 100 million queries) are used most often, while the remaining terms are used less often individually.[13] This example of the Pareto principle (or 80–20 rule) allows search engines to employ optimization techniques such as index or database partitioning, caching and pre-fetching. In addition, studies have been conducted on discovering linguistically-oriented attributes that can recognize if a web query is navigational, informational or transactional.[14]

But in a recent study in 2011 it was found that the average length of queries has grown steadily over time and average length of non-English languages queries had increased more than English queries.[15] Google has implemented the hummingbird update in August 2013 to handle longer search queries since more searches are conversational (i.e. "where is the nearest coffee shop?").[16] For longer queries, Natural language processing helps, since parse trees of queries can be matched with that of answers and their snippets.[17] For multi-sentence queries where keywords statistics and Tf–idf is not very helpful, Parse thicket technique comes into play to structurally represent complex questions and answers.[18]

Structured queries

With search engines that support Boolean operators and parentheses, a technique traditionally used by librarians can be applied. A user who is looking for documents that cover several topics or facets may want to describe each of them by a disjunction of characteristic words, such as vehicles OR cars OR automobiles. A faceted query is a conjunction of such facets; e.g. a query such as (electronic OR computerized OR DRE) AND (voting OR elections OR election OR balloting OR electoral) is likely to find documents about electronic voting even if they omit one of the words "electronic" and "voting", or even both.[19]

See also

References

- Broder, A. (2002). A taxonomy of Web search. SIGIR Forum, 36(2), 3–10.

- Gibbons, Kevin (2013-01-11). "Do, Know, Go: How to Create Content at Each Stage of the Buying Cycle". Search Engine Watch. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Jansen, B. J., Booth, D., and Spink, A. (2008) Determining the informational, navigational, and transactional intent of Web queries, Information Processing & Management. 44(3), 1251-1266.

- Moore, Ross. "Connectivity servers". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Dawn Kawamoto and Elinor Mills (2006), AOL apologizes for release of user search data

- Jansen, B. J., Spink, A., Bateman, J., and Saracevic, T. 1998. Real life information retrieval: A study of user queries on the web. SIGIR Forum, 32(1), 5 -17.

- Silverstein, C., Henzinger, M., Marais, H., & Moricz, M. (1999). Analysis of a very large Web search engine query log. SIGIR Forum, 33(1), 6–12.

- Amanda Spink; Dietmar Wolfram; Major B. J. Jansen; Tefko Saracevic (2001). "Searching the web: The public and their queries". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 52 (3): 226–234. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.23.9800. doi:10.1002/1097-4571(2000)9999:9999<::AID-ASI1591>3.3.CO;2-I. External link in

|title=(help) - Mark Sanderson & Janet Kohler (2004). "Analyzing geographic queries". Proceedings of the Workshop on Geographic Information (SIGIR '04).

- Jansen, B. J., Booth, D. L., & Spink, A. (2009). Patterns of query modification during Web searching. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 60(3), 557-570. 60(7), 1358-1371.

- Jaime Teevan; Eytan Adar; Rosie Jones; Michael Potts (2005). "History repeats itself: Repeat Queries in Yahoo's query logs" (PDF). Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR '06). pp. 703–704. doi:10.1145/1148170.1148326.

- http://www.bing.com/community/site_blogs/b/search/archive/2011/02/10/making-search-yours.aspx

- Ricardo Baeza-Yates (2005). "Applications of Web Query Mining". Advances in Information Retrieval. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3408. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. pp. 7–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-31865-1_2. ISBN 978-3-540-25295-5.

- Alejandro Figueroa (2015). "Exploring effective features for recognizing the user intent behind web queries". 68. Elsevier: 162–169. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mona Taghavi; Ahmed Patel; Nikita Schmidt; Christopher Wills; Yiqi Tew (2011). "An analysis of web proxy logs with query distribution pattern approach for search engines". Computer Standards & Interfaces. 34 (1): 162–170. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2011.07.001.

- Sullivan, Danny (2013-09-26). "FAQ: All About The New Google "Hummingbird" Algorithm". Search Engine Land. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Galitsky B. Machine learning of syntactic parse trees for search and classification of text. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence. 2013;26(3):153–172. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2012.09.017.

- Galitsky B, Ilvovsky D, Kuznetsov SO, Strok F. Finding Maximal Common Sub-parse Thickets for Multi-sentence Search. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. 2013;8323.

- Vojkan Mihajlović; Djoerd Hiemstra; Henk Ernst Blok; Peter M.G. Apers (October 2006). "Exploiting Query Structure and Document Structure to Improve Document Retrieval Effectiveness" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)