Weak ordering

In mathematics, especially order theory, a weak ordering is a mathematical formalization of the intuitive notion of a ranking of a set, some of whose members may be tied with each other. Weak orders are a generalization of totally ordered sets (rankings without ties) and are in turn generalized by partially ordered sets and preorders.[1]

There are several common ways of formalizing weak orderings, that are different from each other but cryptomorphic (interconvertable with no loss of information): they may be axiomatized as strict weak orderings (partially ordered sets in which incomparability is a transitive relation), as total preorders (transitive binary relations in which at least one of the two possible relations exists between every pair of elements), or as ordered partitions (partitions of the elements into disjoint subsets, together with a total order on the subsets). In many cases another representation called a preferential arrangement based on a utility function is also possible.

Weak orderings are counted by the ordered Bell numbers. They are used in computer science as part of partition refinement algorithms, and in the C++ Standard Library.[2]

Examples

In horse racing, the use of photo finishes has eliminated some, but not all, ties or (as they are called in this context) dead heats, so the outcome of a horse race may be modeled by a weak ordering.[3] In an example from the Maryland Hunt Cup steeplechase in 2007, The Bruce was the clear winner, but two horses Bug River and Lear Charm tied for second place, with the remaining horses farther back; three horses did not finish.[4] In the weak ordering describing this outcome, The Bruce would be first, Bug River and Lear Charm would be ranked after The Bruce but before all the other horses that finished, and the three horses that did not finish would be placed last in the order but tied with each other.

The points of the Euclidean plane may be ordered by their distance from the origin, giving another example of a weak ordering with infinitely many elements, infinitely many subsets of tied elements (the sets of points that belong to a common circle centered at the origin), and infinitely many points within these subsets. Although this ordering has a smallest element (the origin itself), it does not have any second-smallest elements, nor any largest element.

Opinion polling in political elections provides an example of a type of ordering that resembles weak orderings, but is better modeled mathematically in other ways. In the results of a poll, one candidate may be clearly ahead of another, or the two candidates may be statistically tied, meaning not that their poll results are equal but rather that they are within the margin of error of each other. However, if candidate x is statistically tied with y, and y is statistically tied with z, it might still be possible for x to be clearly better than z, so being tied is not in this case a transitive relation. Because of this possibility, rankings of this type are better modeled as semiorders than as weak orderings.[5]

Axiomatizations

Strict weak orderings

A strict weak ordering is a binary relation < on a set S that is a strict partial order (a transitive relation that is irreflexive, or equivalently,[6] that is asymmetric) in which the relation "neither a < b nor b < a" is transitive.[1] Therefore, a strict weak ordering has the following properties:

- For all x in S, it is not the case that x < x (irreflexivity).

- For all x, y in S, if x < y then it is not the case that y < x (asymmetry).

- For all x, y, z in S, if x < y and y < z then x < z (transitivity).

- For all x, y, z in S, if x is incomparable with y (neither x < y nor y < x hold), and y is incomparable with z, then x is incomparable with z (transitivity of incomparability).

This list of properties is somewhat redundant, in that asymmetry implies irreflexivity, and in that irreflexivity and transitivity together imply asymmetry.

The "incomparability relation" is an equivalence relation, and its equivalence classes partition the elements of S, and are totally ordered by <. Conversely, any total order on a partition of S gives rise to a strict weak ordering in which x < y if and only if there exists sets A and B in the partition with x in A, y in B, and A < B in the total order.

Not every partial order obeys the transitive law for incomparability. For instance, consider the partial order in the set {a, b, c} defined by the relationship b < c. The pairs a, b and a, c are incomparable but b and c are related, so incomparability does not form an equivalence relation and this example is not a strict weak ordering.

Transitivity of incomparability (together with transitivity) can also be stated in the following forms:

- If x < y, then for all z, either x < z or z < y or both.

Or:

- If x is incomparable with y, then for all z ≠ x, z ≠ y, either (x < z and y < z) or (z < x and z < y) or (z is incomparable with x and z is incomparable with y).

Total preorders

Strict weak orders are very closely related to total preorders or (non-strict) weak orders, and the same mathematical concepts that can be modeled with strict weak orderings can be modeled equally well with total preorders. A total preorder or weak order is a preorder that also is a connex relation;[7] that is, no pair of items is incomparable. A total preorder satisfies the following properties:

- For all x, y, and z, if x y and y z then x z (transitivity).

- For all x and y, x y or y x (connexity).

- Hence, for all x, x x (reflexivity).

A total order is a total preorder which is antisymmetric, in other words, which is also a partial order. Total preorders are sometimes also called preference relations.

The complement of a strict weak order is a total preorder, and vice versa, but it seems more natural to relate strict weak orders and total preorders in a way that preserves rather than reverses the order of the elements. Thus we take the inverse of the complement: for a strict weak ordering <, define a total preorder by setting x y whenever it is not the case that y < x. In the other direction, to define a strict weak ordering < from a total preorder , set x < y whenever it is not the case that y x.[8]

In any preorder there is a corresponding equivalence relation where two elements x and y are defined as equivalent if x y and y x. In the case of a total preorder the corresponding partial order on the set of equivalence classes is a total order. Two elements are equivalent in a total preorder if and only if they are incomparable in the corresponding strict weak ordering.

Ordered partitions

A partition of a set S is a family of non-empty disjoint subsets of S that have S as their union. A partition, together with a total order on the sets of the partition, gives a structure called by Richard P. Stanley an ordered partition[9] and by Theodore Motzkin a list of sets.[10] An ordered partition of a finite set may be written as a finite sequence of the sets in the partition: for instance, the three ordered partitions of the set {a, b} are

- {a}, {b},

- {b}, {a}, and

- {a, b}.

In a strict weak ordering, the equivalence classes of incomparability give a set partition, in which the sets inherit a total ordering from their elements, giving rise to an ordered partition. In the other direction, any ordered partition gives rise to a strict weak ordering in which two elements are incomparable when they belong to the same set in the partition, and otherwise inherit the order of the sets that contain them.

Representation by functions

For sets of sufficiently small cardinality, a third axiomatization is possible, based on real-valued functions. If X is any set and f a real-valued function on X then f induces a strict weak order on X by setting a < b if and only if f(a) < f(b). The associated total preorder is given by setting ab if and only if f(a) ≤ f(b), and the associated equivalence by setting ab if and only if f(a) = f(b).

The relations do not change when f is replaced by g o f (composite function), where g is a strictly increasing real-valued function defined on at least the range of f. Thus e.g. a utility function defines a preference relation. In this context, weak orderings are also known as preferential arrangements.[11]

If X is finite or countable, every weak order on X can be represented by a function in this way.[12] However, there exist strict weak orders that have no corresponding real function. For example, there is no such function for the lexicographic order on Rn. Thus, while in most preference relation models the relation defines a utility function up to order-preserving transformations, there is no such function for lexicographic preferences.

More generally, if X is a set, and Y is a set with a strict weak ordering "<", and f a function from X to Y, then f induces a strict weak ordering on X by setting a < b if and only if f(a) < f(b). As before, the associated total preorder is given by setting ab if and only if f(a)f(b), and the associated equivalence by setting ab if and only if f(a)f(b). It is not assumed here that f is an injective function, so a class of two equivalent elements on Y may induce a larger class of equivalent elements on X. Also, f is not assumed to be a surjective function, so a class of equivalent elements on Y may induce a smaller or empty class on X. However, the function f induces an injective function that maps the partition on X to that on Y. Thus, in the case of finite partitions, the number of classes in X is less than or equal to the number of classes on Y.

Related types of ordering

Semiorders generalize strict weak orderings, but do not assume transitivity of incomparability.[13] A strict weak order that is trichotomous is called a strict total order.[14] The total preorder which is the inverse of its complement is in this case a total order.

For a strict weak order "<" another associated reflexive relation is its reflexive closure, a (non-strict) partial order "≤". The two associated reflexive relations differ with regard to different a and b for which neither a < b nor b < a: in the total preorder corresponding to a strict weak order we get a b and b a, while in the partial order given by the reflexive closure we get neither a ≤ b nor b ≤ a. For strict total orders these two associated reflexive relations are the same: the corresponding (non-strict) total order.[14] The reflexive closure of a strict weak ordering is a type of series-parallel partial order.

All weak orders on a finite set

Combinatorial enumeration

The number of distinct weak orders (represented either as strict weak orders or as total preorders) on an n-element set is given by the following sequence (sequence A000670 in the OEIS):

| Elements | Any | Transitive | Reflexive | Preorder | Partial order | Total preorder | Total order | Equivalence relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 512 | 171 | 64 | 29 | 19 | 13 | 6 | 5 |

| 4 | 65,536 | 3,994 | 4,096 | 355 | 219 | 75 | 24 | 15 |

| n | 2n2 | 2n2−n | ∑n k=0 k! S(n, k) |

n! | ∑n k=0 S(n, k) | |||

| OEIS | A002416 | A006905 | A053763 | A000798 | A001035 | A000670 | A000142 | A000110 |

These numbers are also called the Fubini numbers or ordered Bell numbers.

For example, for a set of three labeled items, there is one weak order in which all three items are tied. There are three ways of partitioning the items into one singleton set and one group of two tied items, and each of these partitions gives two weak orders (one in which the singleton is smaller than the group of two, and one in which this ordering is reversed), giving six weak orders of this type. And there is a single way of partitioning the set into three singletons, which can be totally ordered in six different ways. Thus, altogether, there are 13 different weak orders on three items.

Adjacency structure

Unlike for partial orders, the family of weak orderings on a given finite set is not in general connected by moves that add or remove a single order relation to or from a given ordering. For instance, for three elements, the ordering in which all three elements are tied differs by at least two pairs from any other weak ordering on the same set, in either the strict weak ordering or total preorder axiomatizations. However, a different kind of move is possible, in which the weak orderings on a set are more highly connected. Define a dichotomy to be a weak ordering with two equivalence classes, and define a dichotomy to be compatible with a given weak ordering if every two elements that are related in the ordering are either related in the same way or tied in the dichotomy. Alternatively, a dichotomy may be defined as a Dedekind cut for a weak ordering. Then a weak ordering may be characterized by its set of compatible dichotomies. For a finite set of labeled items, every pair of weak orderings may be connected to each other by a sequence of moves that add or remove one dichotomy at a time to or from this set of dichotomies. Moreover, the undirected graph that has the weak orderings as its vertices, and these moves as its edges, forms a partial cube.[15]

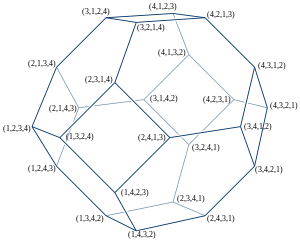

Geometrically, the total orderings of a given finite set may be represented as the vertices of a permutohedron, and the dichotomies on this same set as the facets of the permutohedron. In this geometric representation, the weak orderings on the set correspond to the faces of all different dimensions of the permutohedron (including the permutohedron itself, but not the empty set, as a face). The codimension of a face gives the number of equivalence classes in the corresponding weak ordering.[16] In this geometric representation the partial cube of moves on weak orderings is the graph describing the covering relation of the face lattice of the permutohedron.

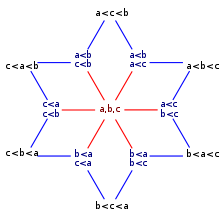

For instance, for n = 3, the permutohedron on three elements is just a regular hexagon. The face lattice of the hexagon (again, including the hexagon itself as a face, but not including the empty set) has thirteen elements: one hexagon, six edges, and six vertices, corresponding to the one completely tied weak ordering, six weak orderings with one tie, and six total orderings. The graph of moves on these 13 weak orderings is shown in the figure.

Applications

As mentioned above, weak orders have applications in utility theory.[12] In linear programming and other types of combinatorial optimization problem, the prioritization of solutions or of bases is often given by a weak order, determined by a real-valued objective function; the phenomenon of ties in these orderings is called "degeneracy", and several types of tie-breaking rule have been used to refine this weak ordering into a total ordering in order to prevent problems caused by degeneracy.[17]

Weak orders have also been used in computer science, in partition refinement based algorithms for lexicographic breadth-first search and lexicographic topological ordering. In these algorithms, a weak ordering on the vertices of a graph (represented as a family of sets that partition the vertices, together with a doubly linked list providing a total order on the sets) is gradually refined over the course of the algorithm, eventually producing a total ordering that is the output of the algorithm.[18]

In the Standard Library for the C++ programming language, the set and multiset data types sort their input by a comparison function that is specified at the time of template instantiation, and that is assumed to implement a strict weak ordering.[2]

References

- Roberts, Fred; Tesman, Barry (2011), Applied Combinatorics (2nd ed.), CRC Press, Section 4.2.4 Weak Orders, pp. 254–256, ISBN 9781420099836.

- Josuttis, Nicolai M. (2012), The C++ Standard Library: A Tutorial and Reference, Addison-Wesley, p. 469, ISBN 9780132977739.

- de Koninck, J. M. (2009), Those Fascinating Numbers, American Mathematical Society, p. 4, ISBN 9780821886311.

- Baker, Kent (April 29, 2007), "The Bruce hangs on for Hunt Cup victory: Bug River, Lear Charm finish in dead heat for second", The Baltimore Sun, archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

- Regenwetter, Michel (2006), Behavioral Social Choice: Probabilistic Models, Statistical Inference, and Applications, Cambridge University Press, pp. 113ff, ISBN 9780521536660.

- Flaška, V.; Ježek, J.; Kepka, T.; Kortelainen, J. (2007). Transitive Closures of Binary Relations I (PDF). Prague: School of Mathematics - Physics Charles University. p. 1. Lemma 1.1 (iv). Note that this source refers to asymmetric relations as "strictly antisymmetric".

- In older sources, connexity is called totality property. However, this terminology is disadvantageous as it may lead to confusion with e.g. the unrelated notion of right-totality, a.k.a. surjectivity.

- Ehrgott, Matthias (2005), Multicriteria Optimization, Springer, Proposition 1.9, p. 10, ISBN 9783540276593.

- Stanley, Richard P. (1997), Enumerative Combinatorics, Vol. 2, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 62, Cambridge University Press, p. 297.

- Motzkin, Theodore S. (1971), "Sorting numbers for cylinders and other classification numbers", Combinatorics (Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., Vol. XIX, Univ. California, Los Angeles, Calif., 1968), Providence, R.I.: Amer. Math. Soc., pp. 167–176, MR 0332508.

- Gross, O. A. (1962), "Preferential arrangements", The American Mathematical Monthly, 69: 4–8, doi:10.2307/2312725, MR 0130837.

- Roberts, Fred S. (1979), Measurement Theory, with Applications to Decisionmaking, Utility, and the Social Sciences, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 7, Addison-Wesley, Theorem 3.1, ISBN 978-0-201-13506-0.

- Luce, R. Duncan (1956), "Semiorders and a theory of utility discrimination" (PDF), Econometrica, 24: 178–191, doi:10.2307/1905751, JSTOR 1905751, MR 0078632.

- Velleman, Daniel J. (2006), How to Prove It: A Structured Approach, Cambridge University Press, p. 204, ISBN 9780521675994.

- Eppstein, David; Falmagne, Jean-Claude; Ovchinnikov, Sergei (2008), Media Theory: Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics, Springer, Section 9.4, Weak Orders and Cubical Complexes, pp. 188–196.

- Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 152, Springer, p. 18.

- Chvátal, Vašek (1983), Linear Programming, Macmillan, pp. 29–38, ISBN 9780716715870.

- Habib, Michel; Paul, Christophe; Viennot, Laurent (1999), "Partition refinement techniques: an interesting algorithmic tool kit", International Journal of Foundations of Computer Science, 10 (2): 147–170, doi:10.1142/S0129054199000125, MR 1759929.