We, the Navigators

We, the Navigators, The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific is a 1972 book by the British-born New Zealand doctor David Lewis, which explains the principles of Micronesian and Polynesian navigation through his experience of placing his boat under control of several traditional navigators on long ocean voyages.

Synopsis

Introduction

David Lewis, after circumnavigating the world in a catamaran, decided to test his understanding of Polynesian navigation techniques by sailing the 2200 miles from Tahiti to New Zealand without any modern instruments (except the smallest of charts and a sky map). After arriving with a landfall only 26 miles in error, he learned that there were contemporary sailors in the Santa Cruz and Caroline Islands who still sailed large distances by the traditional methods and obtained support from the Australian National University to visit and sail with them. He did this in a 39-foot gaff ketch, Isbjorn, which he placed under the direction of the navigators Tevake and Hipour. These navigators spoke very little English, were illiterate and did not understand maps but were able to take him eventually on a 450-mile trip from Puluwat to Saipan and to return and teach him many of their techniques.

The book is largely based on these voyages, but there are extensive references to the literature.

Part 1 - The Puzzle

"Captain Cook in 1775 was uniquely fortunate in encountering Tupaia, a dispossessed high chief and navigator-priest of Raiatea who was the only highly qualified Polynesian navigator who was ever interviewed at length by Europeans." But generally the very idea that people without instruments, charts or writing, could have developed an elaborate and effective art (or "pre-science") of navigation was so utterly foreign as not even to enter the minds of most Europeans. Since then there have been the traditionalists such as Percy Smith who have uncritically accepted the migration legends of the Polynesians as literal history and those, such as Thor Heyerdahl, who dismissed these and emphasised drifting and one-way voyages.

Although the distances involved are thousands of miles, it's possible to traverse the whole ocean with voyages of not more than 310 miles with a few exceptions. The islands of the Pacific can further be grouped into "contact zones" in which the maximum distances are usually 50–200 miles. However, computer simulations have shown that pure drifting cannot explain the distribution of humans across the whole area.

Part 2 - Direction

"The most accurate direction indicators for Pacific Islanders, still used in many parts of Oceania, are stars low in the sky that have either just risen or are about to set, that is horizon or guiding stars ... Although stars rise four minutes earlier each night ... the points on the horizon where they rise and set remain the same throughout the year." Thirty-two such stars were used to form a "sidereal compass" by which directions are given (first described by José Andía y Varela in 1774). Those in the east–west direction which rise in a nearly vertical direction are the easiest to use. Other stars with the same declination must be memorised in order to continue throughout the night. In practice it is rare to require more than ten guide stars for a night's sailing—roughly twelve hours in the tropics—and less for an east–west course. On a cloudy night an experienced navigator can orient himself using only a few stars.

It is harder to use the sun during the day because of the changes in its position during the seasons, and it is necessary to use the swell of the ocean as an aid (not waves, which are local and variable). e.g. in the Santa Cruz group, three swells are considered to be present all round the year: the 'long swell' from the south east, the 'sea swell' from east-north-east and the 'hoahuadelahu' from the north-west. The helmsman detects the most reliable using balance.

Part 3 - Compensation and orientation

For accurate navigation it is essential to compensate for the effect of currents and leeway. Although there are usually swift currents around islands, the major currents take over more than 5–6 miles from land. The major currents are east to west in most parts of Polynesia and Micronesia, but there is a narrow band of the equatorial counter current going west to east. These can make a difference of 40 miles per day.

The prime method of coping with currents is by taking backsights on the land when leaving so as to be able to estimate the current and also the leeway (the angle the boat is drifting off the wind). On many islands, leading marks are set up to aid in this. The course is then adjusted to suit the conditions. There can be daily fluctuations in current but these are generally random and do not accumulate. Expert navigators can also detect currents from the shape of the waves, if the current is confined to the top layers of the water.

Their estimates of distance made good seems to be largely intuitive, based on long experience, and their sense of position derives from keeping in mind where 'home' and other islands are, which can be maintained even when blown far in a gale. They also use the stellar bearings of intermediate islands to judge their progress, even when these are out of sight (a technique known as etak). The memory of the relative position of islands is passed down the generations using the star compass so that a grandson might use a course that hasn't been followed since his grandfather used it.

Part 4 - Expanded target landfall and position

The navigation accuracy required to find an island in the Pacific by sight may be better than 1° and other methods are necessary to make the approach to an island. The basic technique is to "enlarge" the island by identifying signs of approaching land.

Observing the behaviour of seabirds which fly out to their feeding grounds in the morning and return in the evening is one of the most well-known of the techniques. For example, boobies regularly fly 30 miles from an island to forage and some varieties go to 50 miles.

In the Gilbert Islands, characteristic cloud patterns are the preferred means of locating islands. The swell of the sea can be both reflected by an island and refracted round it, giving clues to the experienced navigator in excess of 30 miles. With large land masses such as New Zealand the effect is more pronounced. Another sign which works best on dark rainy nights is deep phosphorescence causing flashes in the sea originating from the island and observable up to 80–100 miles away.

Navigators on several archipelagos were able to home in on an island by observing which stars were overhead, using it as a fix on latitude.

Part 5 - The Lonely Seaways

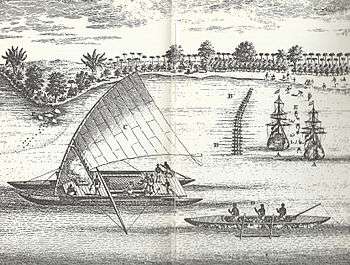

The canoes with which the Polynesians explored the oceans were double canoes which tacked like a European sailing ship whereas the Micronesians used canoes with outriggers on one side which were tacked by reversing the direction of travel, so that the outrigger stayed to windward. The preferred size for long distances throughout Oceania was 50–75 feet, which were least likely to succumb in storms and could carry up to 50 people. The hulls were generally V-shaped made of planks held together by coconut fibre, which would be replaced after a long voyage. They were primarily sailing vessels with auxiliary power provided by paddles. Cook recorded a mean speed of 7 knots close-hauled, which was rather faster than his own vessels. Provisioning allowed for trips up to a month which could be extended by another two weeks without undue hardship. At the present day, the voyaging canoes in the Carolines are smaller, typically 26 feet with a crew of five or six.

The reasons for voyaging vary from recreation to one way trips for colonization. Some of these were accidental and achieved by drifting rather than sailing. Many canoes which storm-drifted to the Philippines from the Yap region made successful returns home. But because of prevailing winds, westerly drifts are far more common than easterly. Tahiti to Hawaii, 2000 miles across the prevailing winds is impossible to drift but fine for sailing. Arriving at Easter Island must have been fortuitous. Raiding and conquest were a traditional motive.

Reception

The Starpath School of Navigation in Seattle says "This is the classic study of Polynesian navigation by one of the world's greatest sailors and adventurers."[1]

In the American Anthropologist, Philip Devita said "Lewis' work is indeed a pioneering effort, a work that should provide Oceanic scholars with a clearly needed understanding of the indigenous navigational practices which remain transmitted in the oral tradition ... The volume is essentially a report of Lewis’ experiments in testing the accuracy of Oceanic landfinding.".[2]

Notes

- The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific, Starpath, retrieved 2 Apr 2015

- Devita, Philip R (1975), "We, the Navigators", American Anthropologist, 77 issue 2 (2): 408–409, doi:10.1525/aa.1975.77.2.02a00670