Wang Mian

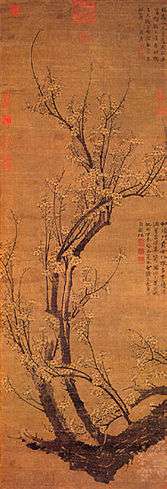

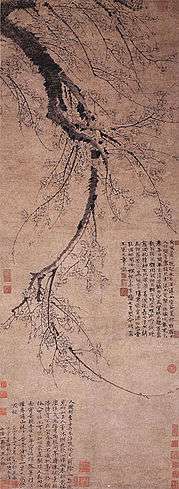

Wang Mian (Chinese: 王冕; pinyin: Wáng Miǎn; Wade–Giles: Wang Mien; 1287–1359), courtesy name Yuanzhang (元章),[1] also known as Zhushi Shannong, was a Chinese painter and poet active during the Yuan dynasty.[2] Initially aspiring to be a government official, Wang later earned considerable recognition as an artist who specialised in plum blossom paintings. Falling out of the public eye in his later years, Wang had a short stint as military adviser to Zhu Yuanzhang. Wang makes an appearance in the fictitious eighteenth-century novel The Unofficial History of the Scholars.

Career

Wang Mian was born in 1287 in Zhuji, Zhejiang.[3] His father was a peasant, but Wang did not wish to follow in his footsteps, and strove to attain a better life. Wang failed to earn a jinshi degree despite having prepared for the imperial examinations.[3] Subsequently, he started practising the "ancient military arts", but this proved to be a similarly fruitless venture. Rejecting numerous job offers in the governmental sector, Wang Mian became a "scholar-in-retirement" bar a short stint as a teacher.[3] Thereafter, Wang began a career as a freelance artist in places like Nanjing and Suzhou,[4] specialising in plum and bamboo[3] paintings that would be accompanied by Wang's poetry.[4] To Wang, plum blossoms "metaphorised his lonely stand in a barbarian-ruled world".[5] He had several sobriquets, including "Zhushi Shannong" (煮石山農).[6]

Wang's reputation as a painter and poet grew, and he was hosted by the Yuan Court's Chief Secretary in Beijing. Following years of traversing China, Wang returned to his hometown in Zhejiang Province, and built a "Plum Blossom Retreat", which had some one thousand plum trees planted around it,[4] at the Kuaiji Mountains, where "(h)e wore old clothes and became known as a mild eccentric".[4] In 1359, in the midst of Zhu Yuanzhang's campaign against the Mongols, Wang acted as a military adviser to Zhu's army, albeit an unsuccessful one, as evidenced by the failure of Wang's plan to seize Shaoxing. Wang died in the same year.[4]

Legacy

According to The New York Times, Wang Mian was one of the earliest artists to write poetry on their artworks. In addition, he was "one of the most distinguished practitioners of the reverse-saturation technique".[7] In his lifetime, Wang penned an autobiography titled Mr Plum Blossom's Autobiography, in which he describes himself as "aloof and noble by temperament, hating to mix with the wealthy and powerful, and defending myself in bitterness and agony".[8] After his death, Wang Mian became a "romantic, semilegendary figure".[4] He is the protagonist of the eighteenth-century Chinese novel Unofficial History of the Scholars by Wu Jingzi.[4] In Unofficial History of the Scholars, Wang's story is heavily dramatised, and his disillusionment with the private sector is attributed not to his failures at the examinations, but his realising "the empty vanity of officialdom". He is also anachronistically written to have become "an anonymous recluse in the mountains" shortly after the establishment of the Ming dynasty by Zhu Yuanzhang.[9] Liu Shiru, who was also from Shaoxing and a respected painter in his own right who published his own plum painting manual, was said to have to been "engrossed" with Wang Mian's works; he "practiced without eating or sleeping" to reach Wang's standards.[10] Okada Hankō wrote a poem referencing Wang Mian to complement his 1838 painting Village Among Plum Trees.[11]

Wang's painting Prunus in Moonlight was displayed at the June 1985 Bones of Jade, Soul of Ice exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery. The New York Times commented that the moon and the flowering plum tree in Prunus in Moonlight "play out the kind of male-female, mind-body, moon-earth drama that is not unfamiliar in 20th-century Western art, particularly after Surrealism", going further to compare Wang with Caspar David Friedrich.[7] In his 1976 book Hills Beyond a River, James Cahill exalts Wang Mian as the "most famous of Yuan plum painters".[3] However, art historian Maggie Bickford labels Wang Mian's art as "plain" and "ambitious" in her 1997 book Ink Plum.[12]

References

Citations

- "故宮書畫數位典藏資料檢索" (in Chinese). National Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Barnhart 1997, pp. 192–193.

- Cahill 1976, p. 160.

- Cahill 1976, p. 161.

- Berg, Daria (2007). Reading China. Brill. p. 58. ISBN 9789004154834.

- 瓷藝與畫藝: 二十世紀前期的中國瓷器 (in Chinese). Hong Kong Municipal Council. 1990. p. 135. ISBN 9789622150980.

- Brenson, Michael (2 June 1985). "Flowering Plum – Chinese motif for the passing of beauty". The New York Times.

- Zhang, Fa (2015). The History and Spirit of Chinese Art. 2. Enrich Professional Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 9781623201289.

- "The Scholars by Wu Jingzu (1701–1754) – Chapter 1". Rutgers University. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Park, J. P. (2017). Art by the Book: Painting Manuals and the Leisure Life in Late Ming China. University of Washington Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780295807034.

- Rotondo-McCord, Lisa (2002). An Enduring Vision. p. 76.

- Chinese Literature, Essays, Articles, Reviews. 19–20. Coda Press. 1997. p. 155.

Bibliography

- Barnhart, Richard M. (1997). Three thousand years of Chinese painting. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300070136.

- Cahill, James (1976). Hills Beyond a River (1st ed.). John Weatherhill. ISBN 0834801205.

External links

- Wang Mian's Plum Paintings at China Online Museum

- Works by Wang Mian at Project Gutenberg

- Sung and Yuan paintings, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Wang Mian (see list of paintings)