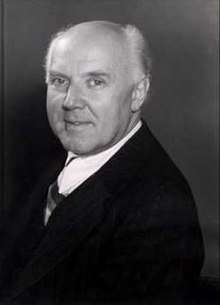

Walter Gieseking

Walter Wilhelm Gieseking (5 November 1895 – 26 October 1956) was a German pianist and composer.

Walter Gieseking | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 November 1895 Lyon, France |

| Died | 26 October 1956 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Pianist, composer |

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Career

Born in Lyon, France, the son of a German doctor and lepidopterist, Gieseking first started playing the piano at the age of four, but without formal instruction. His family travelled frequently and he was privately educated.

From 1911 to early 1916, he studied at the Hanover Conservatory. There his mentor was the director Karl Leimer, with whom he later co-authored a piano method. He made his first appearance as a concert pianist in 1915, but was conscripted in 1916 and spent the remainder of World War I as a regimental bandsman. His first London piano recital took place in 1923, establishing an exceptional and lasting reputation.

During World War II, Gieseking continued to reside in Germany, while continuing to concertize in Europe, and was accused of having collaborated with the Nazi Party. He was criticized for this by pianists Vladimir Horowitz, who, in the book Evenings with Horowitz, calls Gieseking a "supporter of the Nazis," and by Arthur Rubinstein who recounted in his book My Many Years a conversation with Gieseking in which alleges he said "I am a committed Nazi. Hitler is saving our country." Gieseking performed in front of Nazi cultural organizations such as the NS Kulturgemeinde and "expressed a desire to play for the Führer".[1] Along with a number of other German artists, Gieseking was blacklisted during the initial postwar period. By January 1947, however, he had been cleared by the U.S. military government,[2] enabling him to resume his career although his U.S. tour scheduled for January 1949 was cancelled owing to protests by organizations such as the Jewish Anti-Defamation League and the American Veterans Committee. Although there had been other protests (in Australia and Peru, for example), his 1949 American tour was the only group of concerts actually cancelled due to the outcry. He continued to play in many other countries, and in 1953 he finally returned to the United States. His concert in Carnegie Hall was sold out and well received, and he was more popular than ever.

Because of his gifts of a natural technique, perfect pitch, and abnormally acute faculty for memorization, Gieseking was able to master unfamiliar repertoire with relatively little practice. From his early instruction in the Leimer method, he usually studied new pieces away from the piano. It became well known to the public, for instance, that he often committed new works to memory while traveling by train, ship or plane. Sometimes, according to Harold C. Schonberg's book The Great Pianists (1963), he could even learn an entire concerto by heart in one day.

Gieseking had a very wide repertoire, ranging from various pieces by Bach and the core works by Beethoven to the concertos of Rachmaninoff and more modern works by composers such as Busoni, Hindemith, Schoenberg and the lesser-known Italian Petrassi. He gave the premiere of Pfitzner's Piano Concerto in 1923. Today, though, he is particularly remembered for his recordings of the complete piano works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the two French impressionist masters Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, virtually all of whose solo piano music he recorded on LP for EMI in the early 1950s (the Mozart and Debussy sets have recently been re-released on CD), after recording much of it for Columbia in the 1930s and 1940s, some of which have also been re-released on CD.

Gieseking's 1944 performance of Beethoven's "Emperor" Concerto, in which anti-aircraft fire is audible in the background,[3] is one of the earliest stereo recordings, following a rendition of the same work in 1934 for Columbia, with Bruno Walter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. In December, 1955, Gieseking suffered head injuries in a bus accident near Stuttgart, in which his wife was killed.[4]

His last recording project was the complete cycle of Beethoven's Piano Sonatas. Gieseking suddenly fell ill in London, however, while recording Beethoven's "Pastoral" Sonata in D Piano Sonata No. 15 for HMV. He had completed the first three movements and, the following day, was due to record the rondo finale but died a few days later of postoperative complications for the relief of pancreatitis.[5] HMV released the unfinished recording, and since then broadcast recordings of Gieseking playing all of Beethoven's Piano Sonatas (with the exception of Op. 54, which he never recorded) have been issued. Although some of his performances, particularly live, could be marred by wrong notes, Gieseking's best performances, as in studio recording sessions, were virtually flawless.[6]

Parallel to Gieseking's work as a performing artist he was also a composer, but even in his lifetime his compositions were hardly known, and he made no attempt to give them publicity.

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring, BWV 147 French Suite No. 5 in G major, BWV 816 – Gigue in 1939 Here on archive.org |

As Gieseking's father had earned a living as a lepidopterist, Gieseking also devoted much time to the collecting of butterflies and moths throughout his life. His private collection can be seen in the Natural History Collection of the Museum Wiesbaden.

Recordings

Compositions

- The Music of Walter Gieseking – Karen Hand (flute and piano), Nimbus Records, 2001

Notable students

References

- Kater, Michael S. The Twisted Muse : musicians and the music in the Third Reich Oxford 1997

- Clark, Delbert (1947-02-02). "NAZI ARTISTS LEFT TO GERMAN COURTS; Clay Orders End of Reviews of Hearings Conducted by Local Tribunals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- Geraldine Work (March 19, 2017). "Forgotten Pianists: Walter Gieseking". Interlude.hk.

- "Walter Gieseking- Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music". Naxos.com. 1956-09-29. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- The Miami News, October 26, 1956. Walter Gieseking Dies, Famous Concert Pianist

- Dean Elder, Pianists at Play, Kahn & Averill, 1989

Bibliography

- Gieseking, Walter: So wurde ich Pianist (autobiography), Wiesbaden, Brockhaus 1963

- Kater, Michael S. The Twisted Muse : musicians and their music in the Third Reich, New York : Oxford, 1997.

- Leimer, Karl and Gieseking, Walter: The Shortest Way to Pianistic Perfection, Philadelphia, Presser 1932

- —, Rhythmics, Dynamics, Pedal and Other Problems of Piano Playing, Philadelphia, Presser 1938

- Leimer, Karl and Gieseking, Walter: Piano technique, New York, Dover 1972 (contains both books of 1932 and 1938)

- Schonberg, Harold C.: The Great Pianists, 1963

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Walter Gieseking |

- Youngrok Lee's appreciation pages

- Piano Rolls (The Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation)

- Free scores by Walter Gieseking at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Newspaper clippings about Walter Gieseking in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walter Gieseking. |