Waiapu Valley

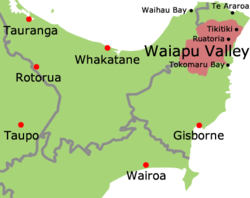

Waiapu Valley, also known as the Waiapu catchment, Waiapu River valley or simply Waiapu, is a valley in the north of the Gisborne Region on the East Coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is the catchment area for the Waiapu River and its tributaries, and covers 1,734 square kilometres (670 sq mi).[2] The Raukumara Range forms the western side of the valley, with Mount Hikurangi in the central west. The towns of Ruatoria and Tikitiki are in the north-east of the valley.

Waiapu Valley | |

|---|---|

Waiapu Valley, with Mount Hikurangi in the centre right of the picture. | |

| |

Waiapu Valley | |

| Coordinates: 37°59′S 178°7′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Gisborne Region |

| Electorate | East Coast |

| Government | |

| • MP | Anne Tolley (National) |

| • Mayor | Meng Foon |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2002) | 2,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| Area code(s) | 06 |

The vast majority of the catchment area lies within the Waiapu and Matakaoa wards of the Gisborne District Council, with the southernmost area in the Waikohu and Uawa wards.[2][3] Some of the most Western points fall within the Coast Ward of the Opotiki District Council in the Bay of Plenty Region.[2][4]

The area is of immense cultural, spiritual, economic, and traditional significance to the local iwi, Ngāti Porou, and in 2002 approximately 90% of its 2,000 inhabitants were Māori.[1][2][5]

Geography

Waiapu Valley is sparsely inhabited, with a population density in 2002 of approximately 1.15/km2 (3.0/sq mi) — less than 8% of the national average at the time (approximately 14.71/km2 or 38.09/sq mi).[2][6][7] The population of the valley is centred in Ruatoria, though the area contains a large number of small settlements.[2][5] In the 2006 census, Ruatoria had a population of 756 — down 9.7% since 2001,[8] and 94.8% of its population were Māori, with 46% of the population able to speak te reo Māori.[9] The second largest town, Tikitiki, is the easternmost point on the New Zealand state highway network.

The western border of the valley is the Raukumara Range, and has a relief ranging from 500 to 1,500 m (1,600 to 4,900 ft). Moving east, the middle and lower parts of the valley are hilly, with a relief of 100–500 m (330–1,640 ft), and the eastern side is made of lower sets of terraces and floodplains just above sea level.[2]

.jpg)

There are many large mountains in the Raukumara Range on the west of the valley, the most prominent of which is Mount Hikurangi, on a spur of the Raukumura Range inland from Ruatoria. At 1,752 m (5,748 ft) above sea level, it is the highest non-volcanic peak in the North Island. Other summits in the area include Whanokao (1,428 m or 4,685 ft), Aorangi (1,272 m or 4,173 ft), Wharekia (1,106 m or 3,629 ft) and Taitai (678 m or 2,224 ft). Together, these mountains provide what Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand calls an "awe-inspiring vista".[10]

The valley receives a high level of rainfall — from 1,600 mm (63 in) per year at the coast, to more than 4,000 mm (160 in) per year in the Raukumura Range.[2] This water drains into a large number of streams and rivers, which flow to Waiapu River, the main stem in the north-east of the valley. The Waiapu River flows north-east from the joining of the Mata River and the Tapuaeroa River near Ruatoria, and reaches the Pacific Ocean near Rangitukia.[2][10][11] Other tributaries in the valley include the Mangaoporo, Poroporo, Wairoa, Maraehara rivers, and the Paoaruku stream.[1] A tributary of the Mata River, the Waitahaia River, is renowned for its brown trout — a European species of fish introduced into New Zealand for fishing in the late 1860s.[12][13]

Environmental concerns

In 1840, approximately 80% of the Waiapu Valley was native forest, with a rich array of native flora and fauna. There was a small area to the east of the river covered in coastal forest and scrub due to partial clearance and burning. Between 1890 and 1930 there was large-scale clearing, felling and burning of native forests for pastoralism. Floods and heavy rainfall are common to the area, and this, combined with the development, resulted in widespread erosion and large amounts of sediment being deposited in the Waiapu River and its tributaries. This has changed the landscape significantly.[2]

Since the late 1960s, much work has been done to repair the area by planting exotic forests in eroding areas, and encouraging the return of native scrub.[2][11] However, by 2002 the catchment area had few natural habitats remaining. It was 37% pasture, 26% exotic Pinus radiata forest, 21% native forest, and about 12% kānuka and mānuka scrub. It was highly degraded and modified, and had extensive and serious erosion problems. About half of the pasture area could be considered erosion-prone and unsustainable. Many of the catchment's rivers were full of sediment, and classed as highly degraded. The Waiapu River had one of the highest sediment yields in the world (20,520 t/km2/year in 2000), more than two and a half times that of the adjacent catchment area of the Waipaoa River.[2] The high level of sediment in Waiapu River means it is undesirable as a source of drinking water, and very little of the river's water is used.[12]

Approximately one sixth of the annual sediment flow in all New Zealand river systems is in the Waiapu River, which continues to be one of the most sediment laden rivers in the world.[10] The annual suspended sediment load is 36 million tonnes, and 90.47 m3 (3,195 cu ft) of sediment flows into the sea every second.[11] Anecdotal evidence suggests that this sediment may have adversely affected nearby coastal and marine environments.[2] Gravel deposited by the river onto shingle beaches near its mouth is extracted at approximately 12 different sites, predominantly for use on nearby rural and forestry roads.[12][14] The water quality of the river's tributaries is often much higher, as they are closer to the native vegetation cover of the Raukumura Range.[12]

In lower areas, much of the eroded gravel from the catchment area settles on the riverbed of the Waiapu River, making it rise rapidly.[11] The riverbed rose 1 metre (3.3 ft) between 1986 and 2007,[15] and a number of bridges in the valley have had to be raised to accommodate their rising riverbeds.[11] As the riverbed rises, so does the river, which is causing extensive riverbank erosion. The banks eroded at a rate of 8 metres (26 ft) per year between 1988 and 1997. By the 2003 to 2008 period this rate had doubled, with 22 metres (72 ft) per year eroding in 2005 and 2006.[15] This erosion threatens the town of Ruatoria, and groynes have been installed in an attempt to divert the river away from the town.[15][16]

Māori history and significance

The Waiapu Valley, called Te Riu o Waiapu in te reo Māori, lies within the rohe of Ngāti Porou, the largest iwi on the East Coast, and second largest in New Zealand.[1][2][5][17] Mount Hikurangi, Waiapu River, and the Waiapu Valley itself are of immense cultural, spiritual, economic, and traditional value to Ngāti Porou.[1][2][5]

Mount Hikurangi is the iwi's most important icon, and in Māori mythology, was the first part of the North Island to emerge when Māui, an ancestor of Ngāti Porou, pulled it as a giant fish from the ocean.[5] According to these beliefs, his waka, Nukutaimemeha, became stranded on the mountain, and lies petrified near the mountain's summit.[5][10] Nine whakairo (carvings) depicting Māui and his whānau were erected on the mountain to commemorate the millennium in 2000 (photo).[10] Another of Ngāti Porou's mythological ancestors, Paikea, is also associated with the mountain. According to myth, Paikea's younger half-brother, Ruatapu, attempted to kill about 70 of his older kin ("brothers") at sea in Hawaiki to exact revenge on his father for belittling him as a low-born son of a slave. The massacre, called Te Huripūreiata, was survived only by Paikea, who called on the sea gods and ancestors to save him.[18] Paikea travelled to New Zealand on the back of a whale, but Ruatapu sent a great flood to kill the survivors in New Zealand, called Te Tai a Ruatapu.[5][18] Mt. Hikurangi became a refuge for the people from this deluge.[5]

The Waiapu River is also of great significance to Ngāti Porou.[1][2][5] According to traditional beliefs, they have had an undisturbed relationship with the river since the time of Māui, which serves to unite those who live on either side of it. Ngāti Porou believe that taniwha dwell in and protect the river, in turn protecting the valley and its hapū. Taniwha believed to be in Waiapu River include Kotuwainuku, Kotuwairangi, Ohinewaiapu, and Ngungurutehorowhatu.[1][19]

Māori settlement of Waiapu Valley was widespread until the 1880s, while in March 1874 there were only 20 Pākehā living in the area.[2][20] In 1840, Ngāti Porou extensively cultivated the area around the river.[2] The valley was a place where they could live, offering safe refuge during periods of war, and supplies of fresh water and various species of fish.[1][5]

The first Māori church in New Zealand was built on the banks of Waiapu River sometime between 1834 and 1839.[21][22] The previous decade, Taumata-a-Kura of Ngāti Porou had been captured by a Ngāpuhi war party, and been made their slave in the Bay of Islands. He escaped several years later, and was protected by the missionaries, who introduced him to Christianity, and taught him to read and write. When he returned to the Waiapu Valley in 1834, he introduced his people to the religion.[22] Richard Taylor's drawing of the church, done after visiting in April 1839, can be viewed here. Whakawhitirā Pā, in which the church was located, was described to Taylor as the largest in the region.[21] Just prior to 1840, the pā had approximately 3,000 inhabitants.[2]

Many Ngāti Porou hapū still live in the valley, which has a large number of marae.[1][23] In 2002, the valley's population was approximately 90% Māori, and traditional culture is still practised in the area — though it has changed significantly in the last 150 years.[2] Since they arrived, the many hapū that live alongside the Waiapu River have been responsible for preserving the mauri (life principle or special nature) of the river, and the hapū of the valley act as kaitiakitanga (guardians) of the river and its tributaries. The techniques the iwi use to catch Kahawai at the mouth of the river are unique to that river, and are considered sacred.[1]

According to an affidavit of Hapukuniha Te Huakore Karaka, two taniwha were placed in strategic locations in the river to protect the hapū from invading tribes — one near Paoaruku (a locality at 37°49′38″S 178°20′21″E[24]) and one at the Wairoa River (a small creek at 37°50′13″S 178°24′00″E[25]). Karaka said that a bridge was built from Tikitiki to Waiomatatini, to the protest of local Māori who were concerned that it would disturb the taniwha. The night before the bridge was completed, a storm came washing the bridge away — the weather till then had been calm. From then, one person would drown in the river nearly every year. If it did not happen one year, two would drown the next. A local tohunga, George Gage (Hori Te Kou-o-rehua Keeti) was approached to help the situation, and after that there were no similar drownings.[19]

The deforestation and land development of the area, largely planned and managed by non-Maori groups, have had a huge negative impact on Māori.[2] In December 2010, Ngāti Porou signed a settlement deal with the New Zealand Government for various grievances, some of which relate to the Waiapu Valley.[1][17] The settlement included a NZ$110 million financial redress, and the return of sites culturally significant to the iwi totally approximately 5,898 hectares (14,570 acres).[17]

Ngāti Porou have a number of whakataukī or pēpeha (sayings or proverbs) relating to Waiapu Valley. These include:

- Ko Hikurangi te maunga, Ko Waiapu te awa, Ko Ngāti Porou te iwi (Hikurangi the mountain, Waiapu the river, Ngati Porou the people). Ngāti Porou's proverb of identity.[2][5]

- Hoake tāua ki Waiapu ki tātara e maru ana (Let us shelter under the thick matted cloak of Waiapu).[5]

- He atua! He tangata! He atua! He tangata! Ho! (Behold, it is divine! It is human! It is divine! It is human! Ah!). Referring to Mt. Hikurangi, this is from the Ngāti Porou haka, Rūaumoko, named after the earthquake god.[5]

- Waiapu kōkā huahua (Waiapu of many mothers). Referring to the valley's large population, its many whānau, and its large number of female leaders.[1][26]:415–6

- Waiapu ngau ringa (Waiapu that blisters the hands). Referring to the hard work required to live in the valley. Men with blistered hands were considered good potential husbands.[26]:416

- Kei uta Hikurangi, kei tai Hikurangi, kia titiro iho ki te wai o te pākirikiri, anō ko ngā hina o tōku ūpoko (In Hikurangi inland is the place, but at the sea coast of Hikurangi look down at the blue cod soup, indeed white as the hair of my head). Singing the praises of home — the white layer of fat on top of the soup showed its high caloric value.[26]:206

19th-century gold prospecting

NB: This section is based on text from Mackay, Joseph Angus (1949). Historic Poverty Bay and the East Coast, N.I., N.Z, available here at The New Zealand Electronic Text Centre.

There were several “gold rushes” in the Waiapu Valley in the early days of European settlement. In 1874 about 100 Māori went prospecting on and around Mount Hikurangi. Sir James Hector, who examined the locality, found no signs of gold. In 1875 “Scotty” Siddons, mate of the Beautiful Star, claimed to have met, on the East Coast, a Māori who had a few ounces of gold. He and a mate named Hill found a lot of mundic on the north-west side of the mountain, but only outcrops of limestone on the higher slopes. In 1886 Reupane te Ana, of Makarika, discovered what he fondly imagined was an enormous deposit of gold. With what Joseph Angus Mackay called “noble unselfishness”, he let all his friends into the secret. Drays, wheelbarrows and receptacles of all kinds were rushed to the scene, and large quantities of the “precious metal” were removed to a safe place. When it turned out that the metal was only mundic, Reupane became an object of ridicule, and, afterwards, was known as “Tommy Poorfellow.”[20]

Notable residents

The area was home to politician Sir Āpirana Ngata, and Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu — the second of three Māori to receive a Victoria Cross.[10][27]

See also

- Waiapu River

- Mount Hikurangi

- Ruatoria

- Tikitiki

- Ngāti Porou

- Gisborne Region

References

- "Deed of Settlement Schedule: Documents" (PDF). Ngāti Porou Deed of Settlement. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Government. 22 December 2010. p. 1. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Harmsworth, Garth; Warmenhoven, Tui Aroha (2002). "The Waiapu project: Maori community goals for enhancing ecosystem health" (DOC). Hamilton, New Zealand: New Zealand Association of Resource Management. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Gisborne District Ward Map" (PDF). Gisborne, New Zealand: Gisborne District Council. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Map of the district" (JPG). Opotiki, New Zealand: Opotiki District Council. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Reedy, Tamati Muturangi (4 March 2009). "Ngāti Porou - Tribal boundaries and resources". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "National population estimates, mean year ended 31 December 1991–2011 – tables" (XLS). Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand. 15 February 2012. Table 1, Cell M100. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Orange, Claudia (7 March 2011). "Northland region - Facts and figures". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Land area. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Population/Dwellings". QuickStats About Ruatoria. Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Cultural Diversity". QuickStats About Ruatoria. Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Soutar, Monty (23 August 2011). "East Coast places - Waiapu River valley". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Gisborne District Council. "Waiapu River". Land & Water New Zealand. The Regional Councils of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Gisborne District Council. "How the river is used". Land & Water New Zealand. The Regional Councils of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Walrond, Carl (1 March 2009). "Trout and salmon - Brown trout". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Gisborne District Council. "Current consents". Land & Water New Zealand. The Regional Councils of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- "Waiapu River Erosion Control Scheme" (PDF). Draft 2012-2022 Ten Year Plan. Gisborne, New Zealand: Gisborne District Council. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Waiapu River flood control". Draft 2012-2022 Ten Year Plan. Gisborne, New Zealand: Gisborne District Council. 18 March 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Finlayson, Hon Christopher (22 December 2010). "Ngāti Porou Deed of Settlement signed" (Press release). New Zealand Government. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Reedy, Tamati Muturangi (18 February 2011). "Ngāti Porou - Ancestors". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Karaka, Hapukuniha Te Huakore (28 July 2000). "Affidavit of Hapukuniha Te Huakore Karaka" (PDF). In the matter of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and in the matter of a claim by Apirana Tuahae Mahuika for and on behalf of Te Runanga o Ngati Porou. Wellington, New Zealand: Rainey Collins Wright & Co. pp. 6–7 Mana Moana/The Waiapu River; paras. 16–17. WAI272. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Mackay, Joseph Angus (1949). "Chapter XXXIX — Local Government: Waiapu County". Historic Poverty Bay and the East Coast, N.I., N.Z. Gisborne, New Zealand: Joseph Angus Mackay. pp. 402–3. Retrieved 7 May 2012. Online version provided by The New Zealand Electronic Text Centre.

- Soutar, Monty (25 September 2011). "East Coast region | Māori churches: Whakawhitirā church in the Waiapu valley (2nd of 2)". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Jones, Martin (2 February 2002). "St Mary's Church (Anglican)". Rarangi Taonga: the Register of Historic Places, Historic Areas, Wahi Tapu and Wahi Tapu Areas. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Historic Places Trust Pouhere Taonga. Brief History. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- Soutar, Monty (25 September 2011). "East Coast region | Marae in the Waiapu River valley". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Manatū Taonga | Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- BE45 - Waipiro Bay (Paoaruku) (Map). 1:50,000. Topo50. Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- BE45 - Waipiro Bay (Wairoa River, Gisborne) (Map). 1:50,000. Topo50. Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Mead, Hirini Moko; Grove, Neil (2003). Ngā Pēpeha a ngā Tīpuna [The Sayings of the Ancestors]. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0-86473-462-4. OCLC 174934126.

- Harper, Glyn; Richardson, Colin (2007). In the Face of the Enemy: The Complete History of the Victoria Cross and New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: HarperCollins. pp. 262–8. ISBN 978-1-86950-650-6. OCLC 154708169.

- Moorfield, John C. "Te Aka Māori-English, English-Māori Dictionary and Index (Online version)". New Zealand: Pearson Education; Auckland University of Technology. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

External links

- Waiapu River valley article in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Ngāti Porou - Tribal boundaries and resources article in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Marae in the Waiapu River valley map and photos in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand