Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine

Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine (Wadzek's Struggle with the Steam Turbine) is a 1918 comic novel by the German author Alfred Döblin. Set in Berlin, it narrates the futile and often delusional struggle of the eponymous industrialist Wadzek against Rommel, his more powerful competitor. In its narrative technique and its refusal to psychologize its characters, as well as in its vivid evocations of Berlin as a modern metropolis, Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine has been read as a precursor to Döblin's better-known 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz.[1]

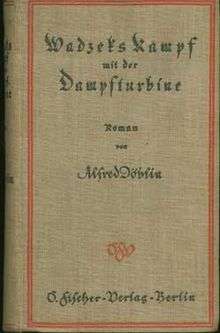

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Alfred Döblin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Fischer Verlag |

Publication date | 1918 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover & Paperback) |

Plot

As the novel opens, Wadzek, owner of a factory that produces steam engines, is locked in a struggle with his more powerful rival Rommel, whose much larger company manufactures turbines. He can be seen as representing a new type of entrepreneur, more technologically advanced and less scrupulous than Wadzek.[2] Losing value, the stock of Wadzek's company is being bought up by Rommel; in desperation, Wadzek teams up with Schneemann, an engineer working at one of Rommel's factories, to thwart his company's takeover by Rommel. This effort includes the misguided theft of some of Rommel's business correspondence. Fearing legal retribution for this theft, Wadzek, accompanied by Schneemann, flees with his wife Pauline and daughter Herta to his house in Reinickendorf, where the two men fortify the house in delusional preparation for a siege that never comes. Financially and spiritually broken, Wadzek returns to Berlin and with Schneemann attempts to turn himself in at a police station, where they learn that no warrant has even been issued for their arrest. There follows a temporary reconciliation with his estranged family and the first attempts to begin a new career in education—Wadzek would instruct his students in a new, moralistic and humane approach to technology. However, after walking in on an erotically and exotically charged debauch held in his own parlor (the aftermath of an African-themed birthday party Pauline held with her two new friends from Reinickendorf), Wadzek suffers a further breakdown. The novel ends aboard a ship bound for America, Wadzek eloping with Gaby, an old acquaintance and erstwhile lover of Rommel's, to begin a new life.

Stylistic and thematic aspects

The novel, originally conceived by Döblin as a novel in "Kino-Stil" ("cinematic style"), is characterized by rapid shifts of perspective and the increasingly sophisticated use of montage.[3] Döblin, having emphatically rejected the psychological novel in his 1913 essay "To novel writers and their critics," presents the reader of Wadzek with a depiction of characters from a perspective that, rather than offering psychological motivations for their actions, opts for a "psychiatric method" that records events and processes without commenting on them or attempting to explain them.[4] Condemned by contemporary critics for its overly-detailed and grotesque descriptive language, the novel's style has since received acknowledgment for its "radical naturalism".[5] Describing the narrative technique used in Wadzek, the critic Judith Ryan has written,

At times Wadzek and his co-actors are seen from without, as if by a [...] camera, at times his perceptions are given from within, but regardless of the observational standpoint, we have no access to Wadzek's psyche. What we know of his emotions and his internal responses to events is solely what we have deduced from his external actions.[6]

Döblin's refusal to make Wadzek a tragic figure, as well as the novel's thematization and satire of tragedy, earned the praise of a young Bertolt Brecht, who declared, "Ich liebe das Buch."[7] Other themes of the novel include monopoly capitalism, modern technology, the bourgeois family, and the modern metropolis. Certain aspects of the plot, such as Schneemann's dislike of Stettin (Szczecin) and Wadzek's elopement for America, recapitulate elements of Döblin's own biography.[8]

Genesis and publication

By his own account, Döblin wrote Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine "in one go" from August to December 1914, at which time he had to begin work as a military doctor near the western front in Sarreguemines.[9] While he had originally conceived of the work as a three-stage narrative about the progress of modern technology (represented by the steam engine, the steam turbine, and the oil motor), his planned sequel, Der Ölmotor (The Oil Motor), never came to fruition.[10] He conducted extensive research for the novel, spending time in the facilities of AEG and learning about the construction of machines, turbines, and motors.[11] Döblin submitted the draft to rigorous stylistic overhaul during the war years, shortening the novel considerably and radicalizing the syntax.[12] The novel was published in May 1918 by Fischer Verlag and was not reprinted until a critical edition, based on the text of the first edition with minor corrections drawn from the manuscript and typescript, was published by Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag in 1987. The original manuscript and subsequent typescript are preserved in the German Literary Archive in Marbach. As of 2016, no English translation is available.

Notes

- Ryan 1981, p. 418; Sander 2001, p. 141

- Sander 2001, p. 140

- Sander 2001, p. 140

- Riley 1987, p. 380

- Riley 1987, p. 370,381; Ryan 1981, p. 419

- Ryan 1981, p. 419

- Riley 1987, p. 383

- Schoeller 2011, p. 146

- Riley 1987, p. 337; Sander 2001, p. 139

- Schoeller 2011, p. 143

- Schoeller 2011, p. 144

- Riley 1987, p. 343

References

- Döblin, Alfred (1987). Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine (in German). Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-423-02424-0.

- Riley, Anthony W. (1987). Editorial Afterword to Wadzeks Kampf mit der Dampfturbine (in German). Munich: Deutsche Taschenbuch Verlag. pp. 363–393. ISBN 3-423-02424-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryan, Judith (November 1981). "From Futurism to 'Döblinism'". The German Quarterly. 54 (4): 415–426. doi:10.2307/405005.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sander, Gabriele (2001). Alfred Döblin (in German). Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 3-15-017632-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schoeller, Wilfried F. (2011). Alfred Döblin: Eine Biographie (in German). Munich: Carl Hanser. ISBN 3-446-23769-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Dollenmayer, David B. The Berlin Novels of Alfred Döblin: Wadzek's Battle with the Steam Turbine, Berlin Alexanderplatz, Men Without Mercy, and November 1918. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. Print.