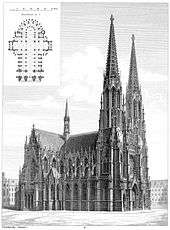

Votivkirche, Vienna

The Votivkirche (English: Votive Church) is a neo-Gothic style church located on the Ringstraße in Vienna, Austria. Following the attempted assassination of Emperor Franz Joseph in 1853, the Emperor's brother Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian inaugurated a campaign to create a church to thank God for saving the Emperor's life. Funds for construction were solicited from throughout the Empire. The church was dedicated in 1879 on the silver anniversary of Emperor Franz Joseph and his wife Empress Elisabeth.[1]

| Votivkirche | |

|---|---|

Votive Church in Vienna at night | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Provostry |

| Leadership | Dr. Joseph Farrugia |

| Year consecrated | 1879 |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Vienna, Austria |

| State | Vienna |

Shown within Austria | |

| Geographic coordinates | 48.215278°N 16.358611°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Heinrich von Ferstel |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Neo-Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1856 |

| Completed | 1879 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | SEbE |

| Length | 85 m (279 ft) |

| Width | 55 m (180 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 30 m (98 ft) |

| Height (max) | 99 m (325 ft) |

| Website | |

| www | |

Origin

The origin of the Votivkirche derives from a failed assassination attempt on Emperor Franz Joseph by Hungarian nationalist János Libényi on 18 February 1853.[2] During that time, when the Emperor was in residence at the Hofburg Palace, he took regular walks around the old fortifications for exercise in the afternoons. During one such stroll, while walking along one of the outer bastions with one of his officers, Count Maximilian Karl Lamoral O'Donnell von Tyrconnell, the twenty-one-year-old tailor's apprentice attacked the twenty-three-year-old Emperor from behind, stabbing him in the collar with a long knife. The blow was deflected by the heavy golden covering embroidered on the Emperor's stiff collar.[2] Although his life was spared, the attack left him bleeding from a deep wound.[3]

A civilian passer-by, Dr. Joseph Ettenreich, came to the Emperor's assistance, and Count O'Donnell struck Libényi down with his sabre, holding him until the police guards arrived to take him into custody.[3] As he was being led away, the failed assassin yelled in Magyar, "Long live Kossuth!" Franz Joseph insisted that his assailant not be mistreated. After Libényi's execution at Spinnerin am Kreuz in Favoriten for attempted regicide, the Emperor characteristically granted a small pension to the assassin's mother.[3]

Dr. Ettenreich, who quickly overwhelmed the attacker, was later elevated to nobility by Franz Joseph for his bravery, and became Joseph von Ettenreich.[4] Count O'Donnell, who up until then was a count in the German nobility by virtue of his great-grandfather, was afterwards made a Count of the Habsburg Empire and received the Commander's Cross of the Royal Order of Leopold. His customary O'Donnell arms were augmented by the initials and shield of the ducal House of Austria and also the double-headed eagle of the Empire. These arms are emblazoned on the portico of No. 2 Mirabel Platz in Salzburg, where O'Donnell later built his residence.[4]

After the unsuccessful assassination attempt, the Emperor's brother, Maximilian — later Emperor of Mexico — called upon communities throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire for donations to a new church on the site of the attack. The church was to be a votive offering for the rescue of Franz Joseph and "a monument of patriotism and of devotion of the people to the Imperial House."[4]

History

The church plans were established in an architectural competition in April 1854. 75 projects from the Austrian Empire, German lands, England, and France were submitted. Originally, the plans were to include the neighbouring Allgemeines Krankenhaus and create a campus fashioned after the plans of Oxford and Cambridge University.

Another plan was to create a national cathedral for all the people of the empire. However, because of spiraling costs and the changing political situation, this plan had to be downsized. The jury choose the project of Heinrich von Ferstel (1828–1883), who, at the time, was only 26. He chose to build the cathedral in the neo-Gothic style, borrowing heavily from the architecture of Gothic French cathedrals. Because of this concept, many people mistake this church for an original Gothic church. However, the Votivkirche is not a servile imitation of a French Gothic cathedral, but rather embodies a new and individual design concept. Furthermore, the Votivkirche was built with one single architect exercising supervision over its entire construction, and not by several generations, as were the cathedrals in the Middle Ages.

Construction began in 1856, and it was dedicated twenty-six years later on April 24, 1879, the occasion of the silver jubilee of the royal couple.

The church was one of the first buildings to be built on the Ringstraße. Since the city walls still existed at that point, the church had no natural parishioners. At that time it was meant as a garrison church, serving the many soldiers that had come to Vienna in the wake of 1848 Revolution. The church is not located directly on the boulevard but along a broad square (now the Sigmund Freud Park) in front of it. The Votivkirche is made out of white sandstone, similar to the Stephansdom, and therefore has to be constantly renovated and protected from air-pollution and acid rain, which tends to colour and erode the soft stone.

The church has undergone extensive renovations after being badly damaged during World War II.

Since its architectural style is quite similar to the Stephansdom, it often gets mistaken for it by tourists, in part because both churches have patterned tiling on their roofs. In reality the two churches differ in age by more than 700 years.

The design of this church has been closely imitated in the Gedächtniskirche in Speyer, Germany, the Cathedral of St. Helena in Helena, Montana, USA, and the Sint-Petrus-en-Pauluskerk in Oostende, Belgium.

Description

The Votivkirche has the typical form of a Gothic cathedral :

- a façade with two slimline towers and three gabled portals with archivolts and a gallery with statues above the portals,

- central portal twice as wide as the side portals

- a rose window, crowned by the roof gable of the nave

- belfries and a transept spire

- buttresses, abutments and flying buttresses

The interior consists of a nave and two aisles, crossed by a transept. This transept has the same height as the nave, while the aisles are only half as high and half as wide as the nave. The side chapels in the transept are as high and wide as the aisles. The choir is surrounded by an ambulatory with apsidioles and a Lady chapel.

This imposing church constitutes a harmonious whole through the proportions, arrangement, spaciousness and unity of style of all the elements.

The Emperor window, donated by the City of Vienna, depicted the delivrance of the Emperor, saved from assassination by Maximilian Graf O'Donnell von Tyrconnell, but this original theme was lost when the windows were destroyed during World War II. The replacement window was restored by the City of Vienna in 1964, albeit modified to reflect the changing times. The detail of the actual moment of the Emperor's deliverance was lost, and although otherwise faithful to the original design, the replacement took on a less monarchical and more religious tone.

Main altar

This impressive altar catches the eye with its gilded retable and an elaborate ciborium over it. The artist Joseph Glasser drew his inspiration for the ciborium from examples in Italian Gothic churches, such as the Basilica of St. John Lateran and the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, both in Rome.

The marble altar is decorated with panels with glass mosaic inlays work. and is supported by six alabaster columns.

A gilded retable stands above the altar, at the bottom of which is the tabernacle, flanked by enameled panels depicting two scenes from the Old Testament: the Sacrifice of Isaac and the dream of Joseph. Above the tabernacle is a niche with a crucifix. Niches surrounding the tabernacle contain statues of angels and various saints. These are: on the left side, statues of the patron saints of the church, Charles Borromeo, and of the founder, Maximilian of Lorch; on the right side, Hilary of Poitiers and Bernard of Clairvaux.

The ciborium is supported by four massive red granite columns. It opens up into four pointed arches, crowned with gables and flanked by pinnacles with statues of saints in their niches. The cross vault is painted with allegorical representations of the four cardinal virtues, while the Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove, is portrayed on the boss. In the spandrel on the front, one can see a mosaic of the Blessed Virgin Mary in her title as the Immaculate Conception, trampling on a snake. This was a gift of Pope Pius IX. In the spire at the top of the ciborium, stands Christ surrounded by four angels.

Transept

The four side chapels in the transept are as high and wide as the aisles : the Rosary chapel, the Chapel of the Cross, the Bishops’ chapel and the baptistry. They form side aisles in the transept, giving the strange impression that the transept is composed of three aisles. Each of these four transept chapels display on their wall pillars four statues of saints. The famous polychrome Antwerp altar in Late-Gothic style (ca. 1530) was in the Rosary chapel till 1986, but is now located in the Museum. The Renaissance sarcophagus of Nicholas, Graf von Salm (defender of Vienna during the Turkish siege in 1529) stands in the baptistry. It was set up as a token of gratitude by emperor Ferdinand I.

Pulpit

The hexagonal Neo-Gothic pulpit stands on six marble pillars. The front panels show us in the middle a preaching Christ, flanked on both sides by the Church Fathers: Saint Augustine, Saint Gregory, Saint Jerome, and Saint Ambrose. These half-reliefs are framed inside sunken medaillons with a gilded mosaic background. Four pillars support the wooden soundboard and on top a spire with a statue of John the Baptist. And just as the sculptor of the Stephansdom has been portrayed under the pulpit of that church, the architect of the Votivkirche, Heinrich Ferstel, has been portrayed under this pulpit by Viktor Tilgner.

Votivpark

The urban park surrounding the church is named Votivpark, which is separated by a street (Straße des achten Mai) from the adjacent Sigmund Freud Park, both of which are located near the Main building (Hauptgebäude) of the University of Vienna.

Gallery

Votivkirche under construction, 1866

Votivkirche under construction, 1866- Choir

- Kreuzaltar in the Kreuzkapelle

Statue of Johannes Nepomuk on the north tower

Statue of Johannes Nepomuk on the north tower Stained glass

Stained glass- Organ

References

- Citations

- Schnorr 2012, p. 69.

- Palmer 1995, p. 66.

- Palmer 1995, p. 67.

- "Attentat auf Kaiser Franz Joseph I". Wein-Vienna (in German). Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Bibliography

- Bousfield, Jonathan; Humphreys, Rob (2001). The Rough Guide to Austria. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1858280592.

- Brook, Stephan (2012). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Vienna. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd. ISBN 978-0756684280.

- Farrugia, Joseph (1990). The Votive Church in Vienna. Ried im Inkreis: Kunstverlag Hofstetter.

- Gaillemin, Jean-Louis (1994). Knopf Guides: Vienna. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0679750680.

- Meth-Cohn, Delia (1993). Vienna: Art and History. Florence: Summerfield Press. ASIN B000NQLZ5K.

- O'Domhnaill, Abu (1987). O'Donnell Clan Newsletter, No. 7.

- Palmer, Alan (1995). Twilight of the Habsburgs: The Life and Times of Emperor Francis Joseph. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0802115607.

- Schnorr, Lina (2012). Imperial Vienna. Vienna: HB Medienvertrieb GesmbH. ISBN 978-3950239690.

- Schulte-Peevers, Andrea (2007). Alison Coupe (ed.). Michelin Green Guide Austria. London: Michelin Travel & Lifestyle. ISBN 978-2067123250.

- Toman, Rolf (1999). Vienna: Art and Architecture. Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 978-3829020442.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Votive Church, Vienna. |

- Votivkirche official website (German)

- Votivkirche, photo gallery in Flickr

- YouTube Video of church, YouTube video showing the inside of the church.