Von der Leyen (family from Krefeld)

Von der Leyen [Laíen] is a German noble family which made its fortune as silk merchants and silk weaving industrialists. The Mennonite family established a major textile business in Krefeld in the 18th century. In its heyday, the business delivered silk to most European courts and aristocratic dynasties. The family was ennobled in 1786 and one branch raised to Baronial rank by Napoleon in 1813 and by the King of Prussia in 1816.

The family is not related to the princely House of Leyen which also bears the name von der Leyen.

History

The first known family member was Peter von der Leyen, mentioned 1579 in Radevormwald where the family produced passementerie; the family name derives from an incorporated village named Leye. In 1656 their Catholic ruler, Philip William, Elector Palatine, introduced high penalty taxes for Anabaptists and Mennonites which made the Mennonite Adolf von der Leyen (c. 1624-1698) seek refuge in the city of Krefeld, at the time ruled by the more tolerant House of Orange-Nassau. Then head of the family Heinrich von der Leyen secured citizenship in 1668 and established his wholesale business.[1] He also continued the family's silk business in the city. In 1693 the Mennonites of Krefeld were allowed to build their own church.

In 1720, Peter von der Leyen founded a factory producing sewing silk, and in 1724, brothers Johann, Friedrich and Heinrich (Adolf's grand sons) founded a silk dyeing factory. The family enterprises expanded rapidly and competed with Cologne companies. Krefeld had come under the rule of the King of Prussia in 1702 and kings Frederick William I and Frederick the Great sought to protect and develop domestic silk production and helped the von der Leyen business to expand further by granting them a silk production monopoly for Prussia. Frederick the Great stayed in the family's Krefeld house after winning the Battle of Krefeld in 1758.

Franz Heinrich Heydweiller inherited the silk-stocking business in 1749 from Peter's widow, who was his mother-in-law.[2] This new company was barred by the government from competing with the parent company. However, it survived and flourished after shifting to the manufacture of velvet ribbons.[2]

By 1763, half of Krefeld's population of 6082 worked for the von der Leyen factories. In 1760, the family founded the Von der Leyen foundation to support local Mennonites and in 1768 gave money for an organ in the Krefeld Mennonite Church.

The family built many factory and residential buildings in Krefeld some of which survived World War II bombardments. The success of the family's silk business has been attributed to the way they operated free from government control.[3] The Von der Leyen monopoly of the silk industry was finally ended during the French occupation in 1794.[1]

.jpg) Peter von der Leyen (1697–1742)

Peter von der Leyen (1697–1742).jpg) Friedrich von der Leyen (1701–1778)

Friedrich von der Leyen (1701–1778).jpg) Heinrich von der Leyen (1708–1782)

Heinrich von der Leyen (1708–1782).jpg) Friedrich von der Leyen (1732–1787)

Friedrich von der Leyen (1732–1787).jpg) Johann von der Leyen (1734–1795)

Johann von der Leyen (1734–1795) Johann von der Leyen's house of 1766/76 in Krefeld

Johann von der Leyen's house of 1766/76 in Krefeld Leyental House, Krefeld, of 1777

Leyental House, Krefeld, of 1777- Leyenburg manor, Rheurdt, of 1772

In the year of Frederick the Great's death, 1786, brothers Conrad, Friedrich and Johann von der Leyen were raised to the rank of hereditary nobility. At the same time when George Washington had the White House built, Conrad von der Leyen commissioned a similar but larger house for himself at Krefeld, between 1791 and 1794, with architect Martin Leydel. In 1860 it was sold to the city of Krefeld and has served as its town hall ever since. When the French Revolutionary Army occupied Krefeld in 1792, General La Marlière took Conrad von der Leyen, some of his relatives and a few other leading citizen as hostages and forced the town to pay him 300.000 guilders. Conrad and his companions in misfortune, however, are said to have won it back for the most part by playing cards with the general.

In 1795 the Left Bank of the Rhine, including Krefeld, was conquered during the War of the First Coalition and annexed by the First French Republic. Friedrich Heinrich von der Leyen (1769-1825), a son of Conrad's brother Friedrich, became mayor of Krefeld in 1800 and founded the local chamber of commerce. In 1803 he purchased Bloemersheim Castle near Neukirchen-Vluyn and the following year Meer Estate in Meerbusch, which are both still owned by the family. In 1804, Napoleon visited Krefeld and stayed in the von der Leyen residence. The following year Friedrich Heinrich became a member of the French Constituent assembly, and in 1813 he was created a hereditary Baron by Napoleon, in 1816 also by the king of Prussia (with the name Baron von der Leyen zu Bloemersheim), when the region had passed back to Prussia after Napoleon's defeat. The silk baron was granted many French and Prussian recognitions.

In 1828, the workers at the von der Leyen factories rebelled against their employers and the 11th Hussar Regiment put down the rebellion. Karl Marx described it as the "first workers' uprising in German history."[4]

Gustav Heinrich, Baron von der Leyen zu Bloemersheim, died in 1857 as the family's last silk producer. He had not succeeded in reestablishing the business to its old success after the Napoleonic Wars. His widow sold the factories and moved to her agricultural estates, which the baronial Bloemersheim branch of the family operates to this day.

Heiko von der Leyen, husband of politician Ursula von der Leyen (former German Federal Minister for Defence and current President of the European Commission), belongs to an ennobled (but not the baronial Bloemersheim) branch of the family.

Bloemersheim Castle

Bloemersheim Castle.jpg) Haus Meer Estate

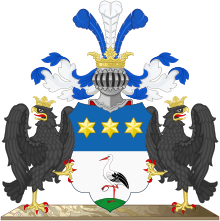

Haus Meer Estate Baronial coat-of-arms

Baronial coat-of-arms

References

- Hunley, J. D. (2019-07-03). Boom and Bust: Society and Electoral Politics in the Düsseldorf Area: 1867-1878. Routledge. ISBN 9781000008081.

- Diefendorf, Jeffry M. (2014). Businessmen and Politics in the Rhineland, 1789-1834. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9781400853786.

- Henderson, W. O. (2006). Studies in the Economic Policy of Frederick the Great. Oxon: Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 0415382033.

- Krefeld - Der Aufstand der Seidenweber, rp-online.de vom 13. Mai 2011

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Von der Leyen. |

- Friedrich and Heinrich von der Leyen on a website on the History of the Rhineland (German)

- 400 Jahre Mennoniten in Krefeld (400 Years of Mennonites in Krefeld, six lectures), Mennonitische Geschichtsblätter, 65. annual compendium, 2008, 360 p., ISBN 978-3-921881-26-2