Volvocaceae

The Volvocaceae are a family of unicellular or colonial biflagellates, including the typical genus Volvox. The family was named by Ehrenberg in 1834,[1] and is known in older classifications as the Volvocidae. All species are colonial and inhabit freshwater environments.

| Volvocaceae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gonium pectorale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Phylum: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Chlorophyceae |

| Order: | Chlamydomonadales |

| Family: | Volvocaceae Ehrenberg |

| Genera | |

| |

Description

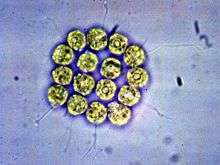

The simplest of the Volvocaeans are ordered assemblies of cells, each similar to the related unicellar protist Chlamydomonas and embedded in a gelatinous matrix. In the genus Gonium, for example, each individual organism is a flat plate consisting of 4 to 16 separate cells, each with two flagella. Similarly, the genera Eudorina and Pandorina form hollow spheres, the former consisting of 16 cells, the latter of 32 to 64 cells. In these genera each cell can reproduce a new organism by mitosis.[2]

Other genera of Volvocaceans represent another principle of biological development as each organism develops differented cell types. In Pleodorina and Volvox, most cells are somatic and only a few are reproductive. In Pleodorina californica a colony normally has either 128 or 64 cells, of which those in the anterior region have only a somatic function, while those in the posterior region can reproduce; the ratio being 3:5. In Volvox only very few cells are able to reproduce new individuals, and in some species of Volvox the reproductive cells are derived from cells looking and behaving like somatic cells. In V. carteri, on the other hand, the division of labor is complete with reproductive cells being set aside during cell division, and they never assume somatic functions or develop functional flagella.[2]

Thus, the simplest Volvocaceans are colonial organisms but others are truly multicellular organisms. Larger volvocaceans have evolved a specialized form of heterogamy called oogamy, the production of small motile sperm by one mating type and relatively larger immotile eggs by another. Among the Volvocaceans are thus the simplest organisms with distinguishable male and female members. In all Volvocaceans, the fertilization reaction results in the production of a dormant diploid zygote (zygospore) capable of surviving in harsh environments. Once conditions have improved the zygospore germinates and undergoes meiosis to produce haploid offspring of both mating types.[2]

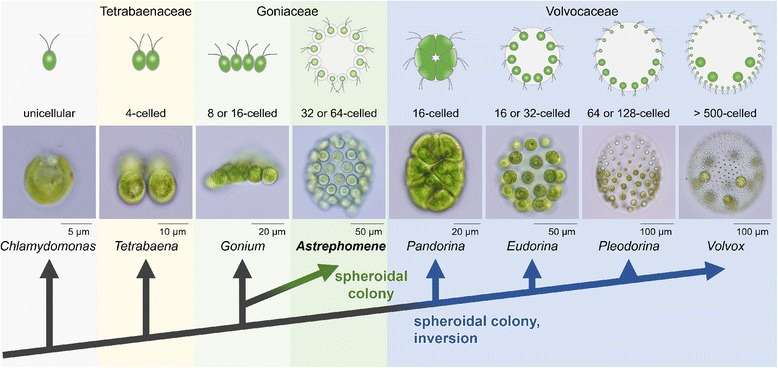

Colony inversion

Colony inversion during development is a special characteristic of this order that results in new colonies having their flagella facing outwards. During this process reproductive cells first undergo successive cell divisions to form a concave-to-cup-shaped embryo or plakea composed of a single cell layer. Immediately after, the cell layer is inside out compared with the adult configuration—the apical ends of the embryo protoplasts from which flagella are formed, are oriented toward the interior of the plakea. Then the embryo undergoes inversion, during which the cell layer inverts to form a spheroidal daughter colony with the apical ends and flagella of daughter protoplasts positioned outside. This process enables appropriate locomotion of spheroidal colonies of the Volvocaceae. The mechanism of inversion has been investigated extensively at the cellular and molecular levels using a model species, Volvox carteri.[3]

Spheroidal colony inversion evolved twice during evolution of the Chlamydomonadales. In the Volvocaceae inversion first occurred when the Volvocaceae diverged from the closely related Goniaceae (see figure). It also occurred during evolution of Astrephomene. Inversion differs between the two lineages: rotation of daughter protoplasts during successive cell divisions in Astrephomene, and inversion after cell divisions in the Volvocaceae. [3]

Notes

- Ehrenberg (1833). "Dritter Beitrag zur Erkenntniss grosser Organisation in der Richtung des kleinsten Raumes" [Third contribution to [our] knowledge of greater organization in the direction of the smallest realm]. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin [Treatises of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin] (in German): 145–336. From p. 281: "VOLVOCINA Nova Familia." (Volvocina New Family.) [Note: According to p. 145, Ehrenberg's paper was first presented in 1832, revised somewhat, and published in 1834.]

- Scott 2000

- Yamashita S, Arakaki Y, Kawai-Toyooka H, Noga A, Hirono M, Nozaki H. Alternative evolution of a spheroidal colony in volvocine algae: developmentalanalysis of embryogenesis in Astrephomene (Volvocales, Chlorophyta). BMC Evol Biol. 2016 Nov 9;16(1):243. PubMed PMID: 27829356; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5103382.

References

- Gilbert, Scott F. (c. 2000). "The Volvocaceans". Developmental Biology. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates, Inc. (NCBI). Retrieved August 9, 2016.

External links

- "Miller Group: Research Description". UMBC Biological Sciences. Retrieved August 9, 2016. (Research on Volvox carteri)