Slavic water spirits

In Slavic paganism there are a variety of female tutelary spirits associated with water. They have been compared to the Greek Nymphs,[1] and they may be either white (beneficent) or black (maleficent).[2] They may be called Boginka (plural Boginky) literally "little goddess",[3] Navia (and Navka or Mavka, pl. Navy, Navky),[1] Rusalka (pl. Rusalky),[3] and Vila (plural Vily).[4]

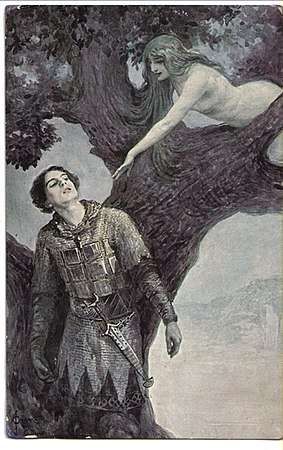

The Proto-Slavic root *navь-, which forms one of the names for these beings, means "dead",[5] as these minor goddesses are conceived as the spirits of dead children or young women. They are represented as half-naked beautiful girls with long hair, but in the South Slavic tradition also as birds who soar in the depths of the skies. They live in waters, woods and steppes, and they giggle, sing, play music and clap their hands. They are so beautiful that they bewitch young men and might bring them to death by drawing them into deep water.[1]

Etymology

Navia, spelled in various ways in the Slavic languages, refers to the souls of the dead.[6] Navka and Mavka (pl. Navky and Mavky) are variations with the diminutive suffix -ka. They are also known as Lalka (pl. Lalky).[7] The Proto-Slavic root *navь-, means "dead", "deceased" or "corpse".[5] The word Nav is also the name of the underworld, Vyraj, which is presided by the chthonic god Veles.[6]

The world of the dead is believed to be separated from the world of the living either by a sea or a river located deep underground.[6] In the folk beliefs of Ruthenia, Veles lives in a swamp located at the centre of Nav, sitting on a golden throne at the base of the world tree, and wielding a sword.[6] Symbolically, the Nav is also described as a huge green plain–pasture, onto which Veles guides the souls.[6] The entrance to Nav is guarded by a zmey, a dragon.[6]

According to Stanisław Urbańczyk, amongst other scholars, Navia was a general name for demons arising from the souls of tragic and premature deaths, the killers and the killed, warlocks, and the drowned.[8] They were said to be hostile and unfavourable towards the living, being jealous of life.[8] In Bulgarian folklore there exists the character of twelve Navias who suck the blood out of women giving birth, whereas in the Primary Chronicle the Navias are presented as a demonic personification of the 1092 plague in Polotsk.[5] According to folk beliefs, Navias may take the form of birds.[6]

Types of water goddesses

Rusalka

According to Vladimir Propp, Rusalka (pl. Rusalky) was an appellation used by the early Slavs for tutelary deities of water who favour fertility, and they were not considered evil entities before the nineteenth century. They came out of the water in spring to transfer life-giving moisture to the fields, thus nurturing the crops.[9]

In nineteenth-century descriptions, however, the Rusalka became an unquiet, dangerous, unclean spirit (Nav). According to Dmitry Zelenin,[10] young women, who either committed suicide by drowning due to an unhappy marriage (they might have been jilted by their lovers or abused and harassed by their much older husbands) or who were violently drowned against their will (especially after becoming pregnant with unwanted children), must live out their designated time on earth as Rusalkas. Original Slavic lore suggests that not all Rusalkas were linked with death from water.[11]

They appear in the form of beautiful girls, with long hair, generally naked but covered with their long tresses, with wreaths of sedge on their heads. They live in groups in crystal palaces at the bottom of rivers, emerging only in springtime; others live in fields and forests. In springtime, they dance and sing along the riverbanks promoting the growth of rye. After the first thunder, they return to their rivers or rise to the skies.[12]

According to Polish folklore, they appeared on new moon and lured young men to play with them, killing them with tickles or frenzied dancing.[13] Sometimes they would ask a riddle, and, if given the right answer, they would leave the man alone.[14] They were particularly mean towards young girls.[14] In some regions they were called majka (pl. majki); in the Tatra Mountains - dziwożona.[13] Other names used to describe this spirit were: water maiden, boginka, moriana and wodiana (the last one became topielica later). A rusalka wasn't necessarily a water spirit - forest ones existed too, and they appeared as more mature than their water counterparts (they also had black hair instead of golden).[13]

They were worshipped together with ancestors during the Rosalia (or Rusalye) festival in spring, originally a Roman festival for offering roses (and other flowers) to gods and ancestors; from the festival derives the term Rusalka itself.[15] Another time associated with the Rusalkas is the green week (or Rusalnaya nedelja, "week of the Rusalkas") in early June; a common feature of this celebration was the ritual banishment or burial of the Rusalka at the end of the week, which remained popular in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine until the 1930s.[16]

Vila

Vila (pl. Vily) are another type of minor goddesses, already identified as Nymphs by the Greek historian Procopius; their name comes from the same root as the name of Veles. They are described as beautiful, eternally young, dressed in white, with eyes flashing like thunders, and provided with wings. They live in the clouds, in mountain woods or in the waters. They are well-disposed towards men, and they are able to turn themselves into horses, wolves, snakes, falcons and swans. The cult of the Vilas was still practised among South Slavs in the early twentieth century, with offerings of fruits and flowers in caves, cakes near wells, and ribbons hanged to the branches of trees.[4]

Names variations

- Boginka, Bogunka, Rusałka (Polish);[3][17][18]

- Navi, Navjaci (Bulgarian);[19]

- Navje, Mavje (Slovenian);[19]

- Nejka, Majka, Mavka (Ukrainian);[19]

- Nemodlika (Bohemian, Moravian);[3]

- Russalka (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian);[3]

- Vila, Wila;[20]

- Samovila, Samodiva (Bulgarian);[20]

- Latawci (Polish).[21]

See also

Gallery of household deities

The Mermaids, 1871, by Ivan Kramskoi

The Mermaids, 1871, by Ivan Kramskoi Rusalky, 1879, by Konstantin Makovsky

Rusalky, 1879, by Konstantin Makovsky Rusalka, 1928, by Sergey Solomko

Rusalka, 1928, by Sergey Solomko Stone representation of spirits in Donetsk

Stone representation of spirits in Donetsk

References

Footnotes

- Máchal 1918, pp. 253–255.

- Máchal 1918, p. 259.

- Mathieu-Colas 2017.

- Máchal 1918, pp. 256–259.

- Kempiński 2001.

- Szyjewski 2004.

- Szyjewski 2004, pp. 79, 199, 206.

- Strzelczyk 2007.

- Ivanits 1989, pp. 78–81; Wayland Barber 2013, p. 18.

- Ivanits 1989, p. 76.

- Wayland Barber 2013, p. 18.

- "Rusalka". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Toronto Press. 2001. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018.

- Encyklopedja Powszechna. Warsaw. 1866. pp. 531–532.

- Moszyński, Kazimierz (1934). Kultura duchowa Słowian [Spiritual Culture of the Slavs]. pp. 608, 632, 684–685.

- Machál 1916, pp. 254, 311–312.

- Ivanits 1989, p. 80.

- N. I. Tolstoy, ed. (1995). Славянские древности: Этнолингвистический словарь [Slavic antiquity. Ethnolinguistic dictionary] (in Russian). 1: А (Август) — Г (Гусь). Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye Otnosheniya. pp. 215–217. ISBN 5713307042.

- "Bogunka". Wielki słownik W. Doroszewskiego. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018.

- Máchal 1918, p. 253.

- Máchal 1918, p. 256.

- Máchal 1918, p. 254.

Sources

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kempiński, Andrzej (2001). Encyklopedia mitologii ludów indoeuropejskich [Encyclopedia of the Mythology of the Indo-European Peoples] (in Polish). Warszawa: Iskry. ISBN 8320716292.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Máchal, Jan (1918). "Slavic Mythology". In L. H. Gray (ed.). The Mythology of all Races. III, Celtic and Slavic Mythology. Boston. pp. 217–389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). "Dieux slaves et baltes" (PDF). Dictionnaire des noms des divinités (PDF). France: Archive ouverte des Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strzelczyk, Jerzy (2007). Mity, podania i wierzenia dawnych Słowian [Myths, Legends, and Beliefs of the Early Slavs] (in Polish). Poznań: Rebis. ISBN 9788373019737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szyjewski, Andrzej (2004). Religia Słowian [The Religion of the Slavs] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. pp. 48, 53, 54, 77–79, 133, 176, 204–207. ISBN 8373182055.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wayland Barber, Elizabeth (2013). The Dancing Goddesses: Folklore, Archaeology, and the Origins of European Dance. W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393089219.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)