Victoria Ponsonby, Baroness Sysonby

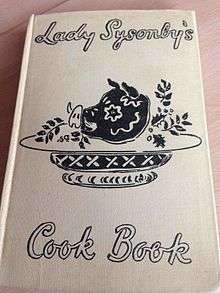

Victoria ("Ria") Lily Hegan Ponsonby, Baroness Sysonby (1874 – 2 June 1955),[1] was a British cookbook author with an "eager and unconventional mind" whose recipes were popular during the 1930s and 1940s.[2][3] Her friend Osbert Sitwell described her book Lady Sysonby's Cookbook as "varied, historic, traditional, and not intended for the rich man's table alone".[4]

Life

Born Victoria Lily Hegan Kennard, the daughter of Colonel Edmund Hegan Kennard, she was also known by the name "Ria". Lady Sysonby said that she took no particular interest in cookery until she got married, on 17 May 1899, to Frederick Ponsonby, 1st Baron Sysonby, the private secretary to Queen Victoria and later to Edward VII.[5] She decided, she said, to study cookery "in a practical way", helped by a collection of recipes inherited from her great-grandmother, her grandmother and mother.[6] Her recipe collection was first published in 1935, the year of her husband's death. Despite their position in the higher echelons of British society, the family were "never particularly well" off, according to The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and at one point had to withdraw their daughter from boarding school because they could not pay the fees.[5] Unlike other upper-class food writers of the interwar years, such as Agnes Jekyll, Ria Sysonby needed the money that her cookbook brought her.[2] But her love of food was wholly genuine, recalled her friend Lord Esher after her death, in a letter to The Times.[3] He remembered her "exquisite cookery", her "original and charming personality" and that she demanded "quality in everything around her".

She and her husband (who went by the nickname "Fritz") had two children: Edward Ponsonby, 2nd Baron Sysonby, and Loelia Lindsay, who married and divorced the second duke of Westminster.

Lady Sysonby served 1916–18 in the French Red Cross in France as a Canteen Worker (two medals).[7] Ria Sysonby died in 1955, after having endured "manifold sufferings" in her later years.[3] She liked to say that her "greatest triumph" was "a caravan holiday when for ten days she did the entire cooking to the unqualified satisfaction of him who ate it" (meaning her husband Fritz).[6]

Work

Lady Sysonby's Cook Book — which was illustrated by Oliver Messel — includes recipes for Soup, Fish, Luncheon Dishes, Meat, Poultry and Game, Vegetables, Salads, Puddings, Savouries, Cakes, Jams and Jellies, Sauces, Sandwiches and Mixed Drinks.[8] She was addressing an upper-middle-class audience, noting for example that "all self-respecting households start the midday meal with a dish usually of eggs in some form or another".[9] In the second edition, in 1948, she addressed the question of postwar scarcity in the kitchen, noting that margarine could be used instead of fresh butter and "top of the milk for cream".[10] She also included a recipe for the wartime favourite, Woolton pie, made from vegetables, white sauce, Bovril and a "small pinch of ginger". Her recipes came from a surprisingly wide range of countries: New Zealand raspberry jam, Hungarian chocolate, Italian gnocchi ("when after a long day, you come in tired and late, this rapidly made rough gnocchi with cheese and herbs is sustaining and easy on the digestion"), Russian cabbage soup, Greek moussaka (her recipe for the latter was a concoction including potatoes, mushrooms, grated carrot and even spaghetti in place of the usual aubergine).[11] She lamented the "fashionable craze of slimming" and the way it caused people to wave away "even the most delicious" of puddings, but noted that "thanks to the war, and the even worse restrictions now, nature has done the thinning for us!"[12]

References

- "The Times". Obituary. 3 June 1955.

- Sage, Lorna (1999). The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English. p. 247. ISBN 978-0521668132.

- Esher (7 June 1955). "The Times".

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. xi.

- Kuhn, William. "'Ponsonby, Frederick Edward Grey, first Baron Sysonby (1867–1935)'". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cookbook. Putnam. dust jacket.

- medal rolls, Kew

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. vii.

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. 37.

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. v.

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. 50.

- Sysonby, Ria (1948). Lady Sysonby's Cook Book. Putnam. p. 125.