Viromandui

The Viromandui or Veromandui (French: Viromanduens, Viromand(ue)s,) were a Belgic tribe of the La Tène and Roman periods, dwelling in the modern Vermandois region (Picardy).[2]

During the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), they belonged to the Belgic coalition of 57 BC against Caesar.[2]

Name

They are mentioned as Viromanduos and Viromanduis by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC),[3] as Viromanduos by Livy (late 1st c. BC),[4] as Veromandui by Pliny (1st c. AD),[5] as (Ou̓i)romándues (<Οὐι>ῥομάνδυες) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[6] and as Veromandi by Orosius (early 5th c. AD).[7][8]

The name Viromandui can be interpreted as the Gaulish Uiro-mandui ('horse-men', or '[men] virile in owning ponies'), composed of uiros ('man') attached to mandus ('pony').[9][10]

The city of Vermand, probably attested as Virmandensium castrum in the 9th c. AD (Virmandi in 1160), and the region of Vermandois, are named after the Belgic tribe.[11][12] A civitas Veromandorum is mentioned in the Notita Galliarum (ca. 400 AD), and it has been debated whether it refers to Vermand or Saint-Quentin.[13]

Geography

Territory

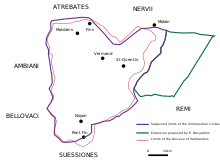

The territory of the Viromandui corresponded for the most part to the limits of the Diocese of Vermandois, around the modern towns of Vermand, Saint-Quentin, Noyon and Moislains.[14] It was located on the 'sill of Vermandois', in an area partly surrounded by dense forests on the upper courses of the Somme and Oise rivers.[2]

They dwelled between the Ambiani and Bellovaci in the west, the Nervii and Atrebates in the north, the Remi in the east, and the Suessiones in the south.[15][14] The Oise river is traditionally regarded as the eastern border between the Viromandui and Remi. Ernest Desjardins, followed by some authors, has proposed that the Viromanduan territory stretched further east until Vervins, although this is debated.[16][17]

Settlements

Late La Tène period

Their main oppidum (16–20 hectares) at the end of the La Tène period and at the beginning of the Roman period, corresponding to the modern town of Vermand, was situated on a promontory east of the Omignon river. Fortifications and continuous occupation emerged relatively late on the site, just before or during the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), and it probably served only as a temporary refuge until the Roman invasion of Belgica. Some have proposed that it was erected as a military camp by Belgic auxiliaries serving in the Roman army.[18] The site remained densely occupied from the Augustan era until the beginning of the 5th century AD.[19]

Roman period

Augusta Viromandorum (modern Saint-Quentin), founded closer to communication axis just 11km away from the oppidum during the reign of Emperor Augustus, soon replaced Vermand as the main settlement.[20] During the Roman period, Augusta Viromandorum reached a size of 40–60ha, in the average of Gallo-Roman chief towns.[21] In the 4th century, the settlement was apparently deserted or its population considerably reduced.[22] Some scholars have argued that Augusta (Saint-Quentin) was replaced by Virmandis (Vermand) as the chief town of the civitas during this period, and that it eventually regained its position in the 9th century.[23][24]

Noviomagus (Gaulish: novio-magos 'new market'; modern Noyon) is first mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary (late 3rd c. AD) as a station on the route between Amiens and Reims.[25] By the 6th century, the influence of the town could rival that of neighbouring towns and it became a local religious centre of power after the bishop Medardus transferred his episcopal siege to Noviomagus in 531.[26]

Other secondary agglomerations were located at Gouy, Contraginum (Condren), Châtillon-sur-Oise, and possibly at Marcy. Gouy was occupied from the 1st century AD until at least the 3rd century. Located in the neighbourhoods of Saint-Quentin, it reached a size of 12ha.[23]

History

La Tène period

According to archaeologist Jean-Louis Brunaux, large-scale migrations occurred in the northern part of Gaul in the late 4th–early 3rd century BC, which may correspond to the coming of the Belgae. The Viromandui were probably already culturally integrated to the Belgae by the 3rd century BC.[27]

Gallic Wars

The Viromandui are perhaps most famous for being a part of a Belgic alliance against the expansion of Julius Caesar. Alongside the Nervii and the Atrebates, they fought against Julius Caesar in the Battle of the Sabis, around 57 BC, named for the river that split the battlefield. We know about this battle because it is described extensively in Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico.[28] He tells how the Belgae surprised the Romans by charging out of the woods while the legions were still constructing the Roman camp. In the initial part of the battle, the Romans lost their camp and took heavy losses, prompting their Gallic allies to desert them. However, they reformed their lines and were finally able to rout the Viromandui and Atrebates, wiping out the Nervii, who reportedly “fought to the last, fighting on top of the corpses of their brethren.” After this battle Caesar went on to destroy all the strongholds of all the Belgic tribes, breaking their power and making them part of the Roman Empire.[29]

The Viromandui and Nervi used cavalry in very small numbers, concentrating on infantry whenever possible. Defensively, they often defeated their enemies' cavalry by forming defensive "hedges", described by Caesar as impenetrable walls of sharpened branches and skillfully cut saplings wrapped in thorns. Using these tactics they resisted the Romans by striking from the safety of their dense forests and marshes.[28]

Roman period

The Viromandui probably gained the status of civitas during the 1st century AD. Roman-era inscriptions mention two Viromanduan serving as magistrates.[30]

Religion

The Gallo-Roman religious site of the "Champ des Noyers" (Marteville, 1km from Vermand) was probably erected on an older Gallic sanctuary, where some weapons of the La Tène period, including a voluntary-deformed sword, were probably involved in a tradition of religious offerings. Three temples (fana) were built during the Roman period at the "Champ des Noyers".[31]

From the beginning of the 1st century AD, a sanctuary was located in Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise, initially centred on a cremation platform used for the sacrifice of caprinae.[32] A temple was erected on the site ca. 150 AD and abandoned ca. 280–290 AD. A vase dedicated to Apollo Vatumarus and deposed as an offering was found in the site, along with the statuette of a mother-goddess, depictions of Risus, and effigies of the Nymphs and Sol.[33][34] The divine name Vatumaros ('High Vātis') is composed of the Gaulish root vāti- ('soothsayer, seer') attached to maros ('high').[35]

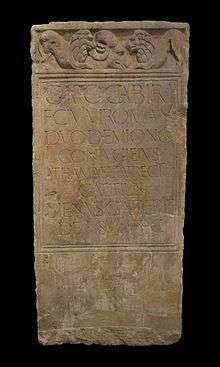

An inscription from Augusta Viromandorum mentions Suiccius as a Viromanduan priest honouring the Imperial numen, and attests the presence of a public cult to the god Vulcan.[30][36] In Condren was found a bas-relief made of stone and depicting Mercury and Rosmerta.[37]

Inscriptions

The Viromandui or their capital Augusta are also mentioned on following inscriptions:

- Viromanduo = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XIII, 1465 (Clermont-Ferrand)

- civi Viromanduo = CIL XIII, 8409, 8341 et 8342 (Koln, I c.)

- Viromand(uo) = CIL XIII, 1688 (Lyon, autel des Gaules)

- Civit (ati) Vi(romanduorum) = CIL XIII, 3528 (Saint-Quentin, end of II or III c.)

- Avg(vstae) Viromandvorv(orum) = CIL VI, 32550 = 2822 et 32551 = 2821 (Rome, middle of III c.)

References

- "Epigraphik Datenbank". db.edcs.eu. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Schön 2006.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:4; 2:16; 2:23

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, 104

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:106

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:6

- Orosius. Historiae Adversus Paganos, 6:7,14

- Falileyev 2010, entry 2424.

- Delamarre 2003, pp. 215, 321.

- Busse 2006, p. 199.

- Nègre 1990, p. 158.

- Collart 2007, pp. 378, 380.

- Beaujard & Prévot 2004, pp. 32–33.

- Ben Redjeb et al. 1992, p. 39.

- Wightman 1985, pp. 12, 26.

- Ben Redjeb et al. 1992, p. 40.

- Pichon 2002, p. 76.

- Collart & Gaillard 2004, p. 494.

- Collart 2007, p. 377.

- Collart 2007, p. 367.

- Collart 2007, pp. 367, 377.

- Collart 2007, p. 378.

- Pichon 2002, p. 82.

- Collart & Gaillard 2004, p. 493.

- Ben Redjeb et al. 1992, p. 37.

- Ben Redjeb et al. 1992, p. 74.

- Pichon 2002, p. 74.

- C. Julius Caesar. De Bello Gallico. English translation by W. A. McDevitte and W. S. Bohn (1869) available on the Perseus Project.

- John N. Hough "Caesar's Camp on the Aisne". The Classical Journal, Vol. 36, No. 6. (Mar., 1941), pp. 337-345.

- Pichon 2002, p. 80.

- Collart 2007, p. 376.

- Cocu & Rousseau 2014, p. 109.

- Cocu et al. 2013, pp. 315–316.

- Cocu & Rousseau 2014, p. 116.

- Cocu et al. 2013, p. 318.

- Collart 1984, p. 249.

- Pichon 2002, p. 84.

Bibliography

- Beaujard, Brigitte; Prévot, Françoise (2004). "Introduction à l'étude des capitales "éphémères" de la Gaule (Ier s.-début VIIe s.)". Supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France. 25 (1): 17–37.

- Ben Redjeb, Tahar; Amandry, Michel; Angot, Jean Pierre; Desachy, Bruno; Talon, Marc; Bayard, Didier; Collart, Jean Luc; Fagnart, Jean-Pierre; Laubenheimer, Fanette; Woimant, Georges-Pierre (1992). "Une agglomération secondaire des Viromanduens : Noyon (Oise)". Revue archéologique de Picardie. 1 (1): 37–74. doi:10.3406/pica.1992.1643.

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Cocu, Jean-Sébastien; Dubois, Stéphane; Rousseau, Aurélie; Van Andringa, William (2013). "Un nouveau dieu provincial chez les Viromanduens : Apollon Vatumarus". Gallia. 70 (2): 315–321. ISSN 0016-4119.

- Cocu, Jean-Sébastien; Rousseau, Aurélie (2014). "Le sanctuaire de Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise: Mutations d'un lieu de culte chez les Viromanduens du I er au IV e s. apr. J.-C". Gallia. 71 (1): 109–117. ISSN 0016-4119.

- Collart, Jean Luc (1984). "Le déplacement du chef lieu des Viromandui au Bas-Empire, de Saint-Quentin à Vermand". Revue archéologique de Picardie. 3 (1): 245–258. doi:10.3406/pica.1984.1446.

- Collart, Jean-Luc; Gaillard, Michèle (2004). "Vermand /Augusta Viromanduorum (Aisne)". Supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France. 25 (1): 493–496.

- Collart, Jean-Luc (2007). "Au Bas-Empire la capitale des Viromandui se trouvait-elle à Saint-Quentin ou à Vermand ?". In Hanoune, Roger (ed.). Les villes romaines du Nord de la Gaule, Actes du XXVe colloque international de Halma-IPEL UMR CNRS 8164. Collection Art et Archéologie. 10. Revue du Nord. Hors-Série. pp. 349–393.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pichon, Blaise (2002). Carte archéologique de la Gaule: 02. Aisne (in French). Les Editions de la MSH. ISBN 978-2-87754-081-0.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Viromandui". Brill’s New Pauly.

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- de Muylder, Marjolaine; Aubazac, Guillaume; Broes, Frédéric; Dubois, Stéphane; Dubuis, Bastien; Font, Caroline; Morel, Alexia (2015). "Un grand domaine aristocratique de la cité des Viromanduens : la "villa" de la Mare aux Canards à Noyon (Oise)". Gallia. 72 (2): 281–299. ISSN 0016-4119.

External links

- The Celtic Tribes of Britain on www.Roman-Britain.org.

- Gallic Settlements: oppida from the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

- Antiquité : Les origines de la ville from a website on Saint-Quentin.

- https://www.livius.org/a/battlefields/sabis/selle.html#2

- Archéologie en Picardie (2000) from the French Ministry of Culture and Communication. (in French)