Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex

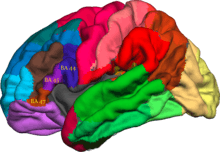

The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex located on the inferior frontal gyrus, bounded superiorly by the inferior frontal sulcus and inferiorly by the lateral sulcus. It is attributed to the anatomical structures of Brodmann's area (BA) 47, 45 and 44 (considered the subregions of the VLPFC – the anterior, mid and posterior subregions).

| Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex | |

|---|---|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex praefrontalis ventrolateralis |

| Acronym(s) | VLPFC |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Specific functional distinctions have been presented between the three Brodmann subregions of the VLPFC.[1][2][3] There are also specific functional differences in activity in the right and left VLPFC.[4] Neuroimaging studies employing various cognitive tasks have shown that the right VLPFC region is a critical substrate of control.[4] At present, two prominent theories feature the right VLPFC as a key functional region. From one perspective, the right VLPFC is thought to play a critical role in motor inhibition, where control is engaged to stop or override motor responses.[5] Alternatively, Corbetta and Shulman[2][6][7] have advanced the hypothesis that there are two distinct frontoparietal networks involved in spatial attention, with the right VLPFC being a component of a right-lateralized ventral attention network that governs reflexive reorienting. From this perspective, the right lateral PFC, along with a region spanning the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ) and the inferior parietal lobule, are engaged when abrupt onsets occur in the environment, suggesting that these regions are involved in re-orienting attention to perceptual events that occur outside the current focus of attention.[4] Also, the VLPFC is the end point of the ventral pathway (stream) that brings information about the stimuli's characteristics.[8]

Functions

The whole right VLPFC is active during motor inhibition, having a critical role, meaning when a person is walking and suddenly stops, the VLPFC activates to stop or override the motor activity in the cortex. The right posterior VLPFC (BA 44) is active during the updating of action plans. The right middle VLPFC (BA 45) responds to decision uncertainty (presumably in right-handed individuals).[4]

See also

- Attention versus memory in prefrontal cortex

- Attentional shift

- Cognitive control

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- Mesocortical pathway

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

- Working memory

References

- Gold, BT; Balota, DA; Jones, SJ; Powell, DK; Smith, CD; Andersen, AH (Jun 2006). "Dissociation of automatic and strategic lexical-semantics: functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for differing roles of multiple frontotemporal regions". J Neurosci. 26 (24): 6523–6532. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0808-06.2006. PMID 16775140.

- Badre, D; Wagner, AD (Oct 2007). "Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory". Neuropsychologia. 45 (13): 2883–901. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.015. PMID 17675110.

- Danker, JF; Gunn, P; Anderson, JR (Nov 2008). "A rational account of memory predicts left prefrontal activation during controlled retrieval". Cereb Cortex. 18 (11): 2674–85. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn027. PMC 2733322. PMID 18321871.

- Levy, BJ; Wagner, AD (2004). "Cognitive control and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex: reflexive reorienting, motor inhibition, and action updating". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1224 (1): 40–62. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05958.x. PMC 3079823. PMID 21486295.

- Aron, AR (2004). "Review Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex". Trends Cogn Sci. 8 (4): 170–7. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. PMID 15050513.

- Corbetta, M; Shulman, GL (Mar 2002). "Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain". Nat Rev Neurosci. 3 (3): 201–15. doi:10.1038/nrn755. PMID 11994752.

- Corbetta, M; Patel, G; Shulman, GL (May 2008). "The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind". Neuron. 58 (3): 306–24. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. PMC 2441869. PMID 18466742.

- Lee, T. G.; Blumenfeld, R. S.; d'Esposito, M. (2013). "Disruption of Dorsolateral but Not Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex Improves Unconscious Perceptual Memories". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (32): 13233–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5652-12.2013. PMC 3735892. PMID 23926275.