Vaudeville Managers Association

The Vaudeville Managers Association (VMA) was a cartel of managers of American vaudeville theaters established in 1900, dominated by the Boston-based Keith-Albee chain. Soon afterwards the Western Vaudeville Managers Association (WVMA) was formed as a cartel of theater owners in Chicago and the west, dominated by the Orpheum Circuit. Although rivals, the two organizations collaborated in booking acts and dealing with the performers' union, the White Rats. By 1913 Edward Franklin Albee II had effective control over both the VMA and WVMA. In the 1920s vaudeville went into decline, unable to compete with film. In 1927 the Keith-Albee and Orpheum chains merged. The next year they became part of the RKO Pictures.

| Formation | 1900 / 1903 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 1927 |

| Type | Association |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Purpose | Vaudeville booking |

| Headquarters | Boston / Chicago |

Region | United States |

Official language | English |

Background

The Theatrical Syndicate was formed in 1896 by Marcus Klaw, A. L. Erlanger Charles Frohman, Al Hayman, Samuel F. Nixon and Fred Zimmerman. Between them they controlled three quarters of the legitimate theaters.[1] Touring companies who booked through the syndicate had to play only in syndicate theaters.[2] Although the syndicate never achieved a monopoly, by 1903 it controlled most first class theater productions.[3]

In 1900 Pat Shea of Buffalo proposed to Benjamin Franklin Keith and Edward Franklin Albee II of Boston that they should set up a similar arrangement for vaudeville. They called a meeting in May 1900 in Boston of most of the major vaudeville managers, including Weber & Fields, Tony Pastor, Hyde & Behman of Brooklyn, Kohl & Castle, Colonel J.D. Hopkins, and Meyerfield & Beck of the Orpheum Circuit of the western USA. They did not invite Frederick Freeman Proctor, Keith's main competitor, but the other managers objected to this and insisted on a meeting in New York where Proctor was invited. The Vaudeville Managers Association (VMA) was founded at the New York meeting.[4] Keith and Albee dominated the new organization.[5]

The purpose of the Vaudeville Managers Association was to end bidding wars for popular acts and eliminate competition between managers for the same audience. The VMA central booking office would arrange all bookings for touring performers in exchange for 5% of their pay.[4] The ground rules for what would become the United Booking Office (UBO) were thrashed out in the VMA meetings.[6] Essentially the VMA was a "monopsony", where a single employer dominates the labor market.[7] Since the theater managers controlled the VMA, they determined the pay and conditions.[8]

Under the new system, acts were booked individually. This forced the break-up of vaudeville companies run by producers who arranged complete travelling shows.[8] On the positive side, performers who paid their dues gained access to the best theaters, with schedules that minimized travel distances and gaps in engagements.[7]

History

The theater managers continued to act independently in setting pay and competing for turf, so the main goals of the VMA were not achieved.[9] After about a year F.F. Proctor left and started booking his own acts. Percy G. Williams of Brooklyn refused to join, so the monopoly was not complete.[5] The Western Managers Association (WMA) originated in 1903 when Meyerfield & Beck of the Orpheum arranged to provide bookings for the Sullivan & Considine theaters in the northwest.[10][11] Various small-time circuits signed up to the WMA for bookings.[10]

The UBO was eventually incorporated in 1906, with the stated aim of eliminating inefficiencies and making sure there was enough proven talent to meet demand.[6] It served the Keith-Albee circuit and many small-time theaters.[12] The UBO had a powerful position. An agent would struggle to get enough bookings for his performers unless he signed up to the UBO, and a theater manager would have difficulty finding enough acts for his shows except by going through the UBO.[13]

The Western Vaudeville Managers Association (WVMA) came into existence when John J. Murdock of Chicago joined up with Beck and others, and blocked expansion of Albee's UBO to Chicago and the west.[10] In a compromise, Martin Beck agreed to book acts for the Orpheum Circuit through the UBO.[11] It was agreed that the WVMA would handle all bookings to the west of the Mississippi and the UBO would handle all bookings to the east.[10] In Chicago the WVMA had arrangements with both the Keith-Albee and the Orpheum.[14] This meant that acts could arrange coast-to-coast tours through one agency.[12]

In 1905 the Orpheum Circuit had seventeen theaters.[15] By 1909 it had grown to twenty-seven theatres.[11] Although the booking agreement held, the two main chains threatened to encroach on each other's territory. In 1911 Beck announced that he was building the Palace Theater on Broadway in Manhattan. In response Albee announced he was building theaters in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Only the Palace was built, and Albee and Keith managed to gain control of it.[10] Albee had secretly acquired 51% of the Orpheum Circuit.[16]

In 1913 the WVMA included over ten circuits and supplied shows to over 300 theaters, mostly in the Midwest, South and West, although it advertised national coverage. The chains included the Orpheum, Gus Sun, Butterfield, Allardt, Theilen, Finn & Heiman and Interstate. The WVMA imposed strict rules, as did the Keith-Albee circuit, to ensure that the shows were suitable for family audiences. "Everything of a vulgar, suggestive, profane or sacrilegious nature is forbidden..."[17] The USA had 2,973 large and small vaudeville theaters by 1913.[18] By 1915 Keith-Albee controlled about 1,500 theaters through the UBO. They imposed their terms on acts, and disciplined those that were late or caused other problems. Most performers had to accept the conditions if they wanted to play big-time theaters.[12]

Union relations

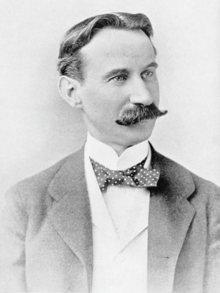

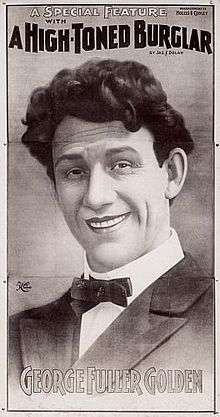

Almost immediately after the VMA was founded the performers responded by forming a union named the White Rats, led by the comedian George Fuller Golden. The White Rats only admitted white males as members. The performers demanded abolition of the 5% commission and went on strike in 1901 after failed negotiations. The Western managers quickly accepted their conditions. Keith met with representatives of the performers and promised to arrange with the other managers for improved conditions.[19] The strike fizzled out with only minor gains.[9]

In 1910 the White Rats was granted a charter by the American Federation of Labor led by Samuel Gompers.[20] In 1911 Albee met with representatives of the Colored Vaudeville Benevolent Association. He told them there was no need for the colored artist to join a union to get work. The managers would look after their interests. Any artist who joined the union would be blacklisted. A hostile report of the meeting in the New York Age asked performers "Does Mr. Albee give you an equitable contract, or does he simply promise to do it? ... Does Mr. Albee treat you like he treats all other artist, like dirt...?"[21]

Albee had a blacklist prepared by John J. Murdock, now his general manager, of all known White Rats. None of them could be employed on a Keith or Orpheum circuit. The Vaudeville Managers Protective Association (VMPA) was formed to enforce the blacklist.[22] Albee set up the National Vaudeville Artists (NVA) as an alternative union under his control. Performers who wanted bookings on the Keith or Orpheum circuits had to warrant that they were NVA members.[23]

In 1916 Harry Mountford of the White Rats organized a strike against the UBO that began in Oklahoma City and then spread to Boston and New York.[20] The strikes failed and the White Rats went bankrupt. In May 1918 the Federal Trade Commission charged that the Vaudeville Managers Protective Association was an illegal combination operating in restraint of trade. It dominated big-time vaudeville, forced performers to pay excessive fees and punished union members through the blacklist. The FTC also named the NVA, UBO and the Keith Vaudeville Collection Agency.[24] Marcus Loew, who had regional agencies for Famous Players and Universal Pictures, was seen as a co-conspirator by the government because many of the Keith theaters showed Loew-controlled films.[24] The only result of the hearings was that the VMPA agreed to drop the requirement for a performer to belong to the NVA to obtain bookings.[25]

In 1919 Albee acquired the former White Rats clubhouse as NVA headquarters.[23] In March 1924 an article in Equity magazine said the NVA "was formed so that the vaudeville artists could be herded into an organization under the control of the vaudeville managers. The N.V.A. is a lightning rod down which the collective strength of the vaudeville actor runs harmlessly into the ground."[23]

In the 1920s a small hospital/lodge was built in Saranac Lake, New York, for performers ailing from tuberculosis and other respiratory ailments. Later a larger hospital was built in the mid to late 1920s. It was called the National Vaudeville Artist Lodge. After the NVA went bankrupt and merged with what later became RKO in the 1930s, the hospital was renamed the Will Rogers Memorial Hospital. The Tudor mansion still stands today as a retirement home. It was painstakingly restored and looks exactly as it did when it was originally built.

Funds for the building and the upkeep of the hospital were raising through annual benefits in which many artists performed. To commemorate these efforts, souvenir books were created, featuring photographs of the many performers, a list of who was performing, cartoons, and poems written by performers.

Decline and dissolution

In 1929 the National Vaudeville Artists was taken in a hostile move by Joseph Kennedy. He kept Albee only as a figure head. One day Albee had a idea and was immediately told "You are nothing" A year and half later Albee died. Some of the theaters began offering combinations of film and vaudeville, or film only.[10] This mix of film and vaudeville remained popular for many years. By 1925 the Albee-Keith chain was down to 350 theaters. By 1926 there were only twelve theaters dedicated to big-time vaudeville.[18] In 1927 the Orpheum merged with the Keith-Albee chain. In October 1928 the consolidated Keith-Albee-Orpheum company combined with the Radio Corporation of America and the Film Booking Office. The new company was called Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO). The former vaudeville theaters became cinemas.[26]

References

Citations

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 252.

- Davis 2010, p. 182.

- Cobrin 2009, p. 177.

- Stewart 2006, p. 122.

- Stewart 2006, p. 124.

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 1139.

- Haupert 2006, p. 15.

- Stewart 2006, p. 123.

- Stewart 2006, p. 126.

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 852.

- Rogers, Gragert & Johansson 2001, p. 54.

- Haupert 2006, p. 16.

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 1140.

- Haupert 2006, p. 25.

- Rogers, Gragert & Johansson 2001, p. 53.

- Sanjek 1988, p. 18.

- Rogers, Gragert & Johansson 2001, p. 291.

- Mates 1987, p. 159.

- Stewart 2006, p. 125.

- Slide 2012, p. 554.

- Sampson 2013, p. 265.

- Sanjek 1988, p. 19.

- Slide 2012, p. 368.

- Sanjek 1988, p. 20.

- Sanjek 1988, p. 21.

- Rogers, Gragert & Johansson 2001, p. 55.

Sources

- Cobrin, Pamela (2009). From Winning the Vote to Directing on Broadway: The Emergence of Women on the New York Stage, 1880-1927. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-058-4. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; McNeilly, Donald (2004). Vaudeville old & new: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Andrew (2010). America's Longest Run: A History of the Walnut Street Theatre. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-03578-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haupert, Michael John (2006-01-01). The Entertainment Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-313-32173-3. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mates, Julian (1987). America's Musical Stage: Two Hundred Years of Musical Theatre. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-92714-1. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rogers, Will; Gragert, Steven K.; Johansson, M. Jane (2001-05-01). The Papers of Will Rogers: From vaudeville to Broadway : September 1908-August 1915. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8061-3315-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sampson, Henry T. (2013-10-30). Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musical Shows. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8351-2. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanjek, Russell (1988-07-28). American Popular Music and Its Business : The First Four Hundred Years Volume III: From 1900 to 1984: The First Four Hundred Years Volume III: From 1900 to 1984. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-504311-2. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slide, Anthony (2012). The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-61703-250-9. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, D. Travis (2006-10-31). No Applause--Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-1-4299-3041-3. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)