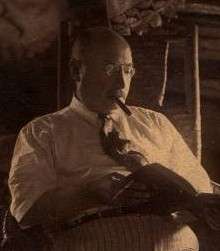

Percy G. Williams

Percy Garnett Williams (May 4, 1857 – July 21, 1923) was an American actor who became a travelling medicine salesman, real estate investor, amusement park operator and vaudeville theater owner and manager. He ran the Greater New York Circuit of first-class venues. Williams was known for giving generous pay and good working conditions to performers. At his death, he endowed his Long Island house as a retirement home for aged and destitute actors.

Percy G. Williams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 4, 1857 Baltimore, Maryland, US |

| Died | July 21, 1923 (aged 66) |

| Occupation | Vaudeville theater manager |

| Known for | Greater New York Circuit |

Early years

Percy Garnett Williams was born on May r, 1857, in Baltimore, Maryland.[1] He was the son of John B. Williams, a doctor and editor of the Baltimore Family Journal. Percy Williams was expected to also become a doctor, and after graduating from Baltimore College he studied medicine for a while. However, he was fascinated with theater.[2] He organized and became the manager of the Courtland Dramatic Club.[3] He played at the Front Street Theatre and Colonel Sinn's Theatre in Baltimore, then moved to Brooklyn in 1875, where he performed with Colonel Sinn's Park Theatre.[3] He spent two seasons in Brooklyn, then returned to Baltimore and was the leading comedian in the Holliday Street Theater stock company.[2] He performed in a traveling production of Uncle Tom's Cabin that received good reviews.[4]

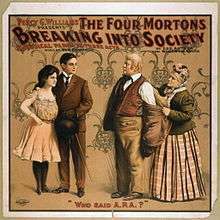

In 1880 Williams launched a travelling medicine show, hawking "liver bags". These contained various herbs plus a charged battery attached to a belt. Williams would enlist a local citizen in each town he visited to try wearing a liver bag, and to then tell the public how much better he felt.[3] At first the show was just a blackface song and dance routine by Williams accompanied by a banjo player. Williams sold the liver belts in the intermissions. Later the show expanded and was staged in a tent. Williams began organizing other acts to sell the liver belts.[3] He would book halls and put on variety shows.[5] Eventually he had sixty acts working for him, often as part of another travelling show.[3][lower-alpha 1]

Bergen Beach

Williams began investing in real estate around the end of the 1880s. He partnered with Thomas Adams, the chewing gum magnate, to buy what is now Bergen Beach, Brooklyn. This was 300 acres (120 ha) of marshland in Brooklyn west of Rockaway and south of Flatbush on Jamaica Bay.[3] Williams and Adams had meant to build housing, but decided to emulate the successful Coney Island.[4] They converted Bergen Island into a resort. It was accessible via the Flatbush Avenue streetcar, now the B41 bus route.[6] The resort opened in 1893 with a dance hall, concessions, rides and a pier.[7] The Percy Williams Amusement park opened in June 1896, later just called Bergen Beach.[8] Williams also opened Zip's Casino, a beer hall in Manhattan's Lower East Side.[3]

In March 1902 the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company offered to buy the Bergen Beach resort, but would not meet Williams' price. For a while trolley service to the beach was cut and business suffered, but trolley service was later improved again. The resort was damaged by two fires in 1904 and 1910. It was open again by 1915, but had closed by 1919.[8]

Theaters

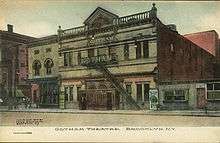

Williams bought the Brooklyn Music Hall in 1897, later changing its name to the Gotham. He also ran the Novelty in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, sometimes shuttling acts by carriage so they could play both theaters on the same day.[3] The Vaudeville Managers Association was formed in 1900 in an attempt to contain the salaries paid to performers. Williams refused to join. He believed in paying well and giving the performers good conditions. Performers found him a modest and approachable man, and enjoyed working for him.[5] Williams' third theatre was the Orpheum in Brooklyn.[3] He opened the Orpheum in 1901 on a plot of land he had bought in 1895. At the time it was thought to be the most beautiful theater in the world.[5]

Percy Williams continued to expand his operation, partnering with wealthy and well-connected men who could overcome problems with permits and licenses. He built or leased the Greenpoint, Crescent and Bushwick theaters in Brooklyn, the Bronx Opera House, the Circle and Colonial theaters in Manhattan, the Alhambra in Harlem, a theater in Philadelphia and another in Boston.[3] As of 1905 the theater owners who booked through the William Morris Agency seemed likely to become dominant in the vaudeville industry. They included Williams, Frederick Freeman Proctor, Timothy Sullivan and Willie Hammerstein. However, E.F. Albee was building up the Keith-Albee circuit into the largest vaudeville chain east of the Mississippi. Albee created the United Booking Office (UBO) to coordinate and regulate vaudeville, and became the UBO general manager.[3] Williams resisted joining the UBO, but was eventually persuaded to become the UBO business manager. He was pushed into this move by competition from A. L. Erlanger and Lee Shubert.[9]

The city of New York had "Blue Laws" that banned theatrical performances on Sundays, but did not enforce them strictly. Mayor George B. McClellan ordered their enforcement in 1907. In protest, the theaters closed down until the mayor was forced to ease up. Williams took the city to court over the laws, and won his case before the New York State Supreme Court.[1]

William's Orpheum Company advertised "Clean Shows in Clean Houses." In 1907 Mae West performed at the Gotham Theater as a child actor in Hal Clarendon's stock theater company.[10] Williams looked for acts in Europe, and signed contracts with Vesta Victoria, Vesta Tilley and Marie Lloyd among others.[2] In 1909 Williams joined The Lambs, the famed theatrical club.[11] In 1910 Williams staged a production called The Wow-Wows at the Alhambra, Bronx, Orpheum, Greenpoint and Colonial Theatres. Players who appeared in this show included Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel.[1] In 1910 Williams was managing more vaudeville theaters in New York City than any other. He had two in Manhattan and one each in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens. He said that after several trips to the Old World to search for talent he found that all he was looking for was in the USA.[12] He said of vaudeville performers,

The great thing about vaudeville is that each and every one must depend on his or her own ability. You are not a trained puppet, giving voice to the ideas of a stage manager whose conception may or may not be correct. You do your own staging, the theater gladly furnishing you with anything in the way of props or mechanical effects that will in any way enhance the value of your act, but nowhere in the world can the expression "make good" be more aptly used than in the world of vaudeville.[12]

Last years

By 1912 Williams was financially involved in eight highly profitable theaters in New York City. He was sick, suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, and lived in Florida part of the year.[9] Both Albee and Martin Beck of the Orpheum Circuit wanted these theaters, Albee so his circuit would gain a dominant position in New York, and Beck so his circuit would become the first coast-to-coast vaudeville operation in the USA. Albee made the higher bid, and acquired Williams' theater interests for $5.25 million.[9]

Percy Williams became a thirty-second degree Mason and grand treasurer of the Elks for the United States.[2] He died on 21 July 1923 at East Islip, New York, on Long Island. He was aged 66. His will said "I made my money from the actors; I herewith return it to them."[7] He bequeathed his 48 acres (19 ha) home in East Islip as a home for aging and destitute actors, with a fund for their maintenance. Most of the property, including a nine-hole golf course, was sold by the trustees in 1973 so they could expand the Actors Fund Home in New Jersey.[9]

Bergen Beach was sold off in lots after 1925. Bergen House was razed around 1930. What was left of the boardwalk and amusement park were torn down in 1939. The Belt Parkway now runs through the area.[6] The Gotham closed in 1934 and was demolished to make way for a parking lot.[10] The Orpheum became part of the RKO chain, and was converted to showing only films after the Albee Theatre opened in 1925. It was closed early in the 1950s and was left unused until it was demolished.[13] The 1,265-seat Colonial Theatre on Broadway, which Williams bought in April 1905 shortly after it opened, was renamed Keith's Colonial in 1912 and continued as a big-time vaudeville venue. Later it became Hampden's Theatre, the RKO Colonial cinema, an NBC and then ABC television studio, and in 1974 briefly became home of the Harkness Ballet.[14] The theater closed in 1977. It was torn down and replaced by condominiums and a plaza.[15]

References

Notes

- His New York Times obituary summarized the travelling medicine show period of his life as "For a time he manufactured electrical goods, and, it is said, profitably..."[2]

Citations

- Tara 2001.

- Percy G. Williams, NYT 1923, p. 5.

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 1215.

- Rubin 2012, p. 70.

- Stewart 2006, p. 124.

- Bergen Beach Playground, NYC parks.

- Slide 2012, p. 559.

- Stanton 2014.

- Cullen, Hackman & McNeilly 2004, p. 1216.

- Gomes 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-08. Retrieved 2015-12-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- What the Season Promises... NYT 1910.

- Orpheum Theatre, NYC AGO.

- Rogers, Gragert & Johansson 2001, p. 237.

- Colonial Theatre, Cinema Treasures.

Sources

- "Bergen Beach Playground". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- "Colonial Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; McNeilly, Donald (2004). Vaudeville old & new: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gomes, Riccardo (2014). "Gotham Theater". East New York Project. Retrieved 2014-05-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Orpheum Theatre". NYC Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- "Percy G. Williams". The New York Times. 22 July 1923. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- Rogers, Will; Gragert, Steven K.; Johansson, M. Jane (2001-05-01). The Papers of Will Rogers: From vaudeville to Broadway : September 1908 – August 1915. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-8061-3315-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubin, Lucas (2012). Brooklyn's Sportsmen's Row: Politics, Society and the Sporting Life on Northern Eighth Avenue. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-273-1. Retrieved 2014-05-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slide, Anthony (2012). "Percy G. (Garnett) Williams". The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-61703-250-9. Retrieved 2014-05-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanton, Jeffrey (2014). "BERGEN BEACH - Brooklyn, NY". Retrieved 2014-05-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, D. Travis (2006-10-31). No Applause--Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-1-4299-3041-3. Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tara (2001). "Percy G. Williams, 1857-1923". Retrieved 2014-05-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "What the Season Promises for Patrons of Vaudeville: Percy G. Williams" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 September 1910. Retrieved 2014-05-17.