Cosmatesque

Cosmatesque, or Cosmati, is a style of geometric decorative inlay stonework typical of the architecture of Medieval Italy, and especially of Rome and its surroundings. It was used most extensively for the decoration of church floors, but was also used to decorate church walls, pulpits, and bishop's thrones. The name derives from the Cosmati, the leading family workshop of craftsmen in Rome who created such geometrical marble decorations.

The style spread across Europe, where it was used in the most prestigious churches; the high altar of Westminster Abbey, for example, is decorated with a Cosmatesque marble floor.[1][2]

Description and early history

The Cosmatesque style takes its name from the family of the Cosmati, which flourished in Rome during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and practiced the art of mosaic. The Cosmati's work is peculiar in that it consists of glass mosaic in combination with marble. At times it is inlaid on the white marble architraves of doors, on the friezes of cloisters, the flutings of columns, and on sepulchral monuments. Again, it frames panels, of porphyry or other marbles, on pulpits, episcopal chairs, screens, etc., or is itself used as a panel. The colour is brilliant, gold tesserae being freely used. While more frequent in Rome than elsewhere in Italy, its use is not confined to that city. Among other locations it is found in the Cappella Palatina in Palermo. Precisely what its connection may be with the southern art of Sicily has yet to be determined.[3]

Although the Cosmati of 12th Century Rome are the eponymous craftsmen of the style, they do not seem to have been the first to develop the art. A similar style may be seen in the pavement of the Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino (1066–1071), built using workers from Constantinople, making it likely that the geometric style was heavily influenced by Byzantine floor mosaics. However, the technique is distinct because Cosmati floors are made from variously shapes and sizes of stone, a property quite different from opus tessellatum mosaics in which the patterns are made from small units which are all the same size and shape. The stone used by the Cosmati artists were often salvaged material (cf. upcycling) from the ruins of ancient Roman buildings, the large roundels being the carefully cut cross sections of Roman columns.[4]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, this style of inlaid ornamental mosaic was "introduced into the decorative art of Europe during the twelfth century by a marble-worker named Laurentius [also known as "Lorenzo Cosmati"[5]], a native of Anagni, a small hill-town sixty kilometres east-south-east of Rome. Laurentius acquired his craft from Greek masters and followed their method of work for a while, but early in his career developed an original style. Freeing himself from Byzantine traditions and influences, Laurentius' style evolved into a decorative architectural mosaic, vigorous in colour and design, which he employed in conjunction with plain or sculpted marble surfaces.

"As a rule he used white or light-coloured marbles for his backgrounds; these he inlaid with squares, parallelograms, and circles of darker marble, porphyry, or serpentine, surrounding them with ribbons of mosaic composed of coloured and gold-glass tesseræ. These harlequinads he separated one from another with marble mouldings, carvings, and flat bands, and further enriched them with mosaic. His earliest recorded work was executed for a church at Fabieri in 1190, and the earliest existing example is to be seen in the church of Ara Coeli at Rome. It consists of an epistle and gospel ambo, a chair, screen, and pavement.

"In much of his work he was assisted by his son, Jacobus, who was not only a sculptor and mosaic-worker, but also an architect of ability, as witness the architectural alterations carried out by him in the cathedral of Civita Castellana, a foreshadowing of the Renaissance. This was a work in which other members of his family took part, and they were all followers of the craft for four generations. Those attaining eminence in their art are named in the following genealogical epitome: Laurentius (1140–1210); Jacobus (1165–1234); Luca (1221–1240); Jacobus (1213–1293); Deodatus (1225–1294); Johannes (1231–1303)."[6]

Terminology

Cosmatesque work is also known as opus alexandrinum.[7] Definitions of this term, and the distinction between it and opus sectile, vary somewhat. Some restrict opus alexandrinum to the typical large designs, especially for floors, using white guilloche patterns filled in with roundels and bands in coloured designs using small pieces.[8] Others include any geometric design including large pieces, as in the picture from Spoleto (right side) below, whereas opus sectile also includes figurative designs made in the same technique.

Opus alexandrinum is another form of opus sectile, where but few colours are used, such as white and black, or dark green on a red ground, or vice versa. This term is particularly employed to designate a species of geometrical mosaic, found in combination with large slabs of marble, much used on the pavements of medieval Roman churches and even in Renaissance times, as, for instance, on the pavements of the Sistine Chapel and the Stanza della Segnatura.

Examples in Rome

Among the churches decorated in cosmatesque style in Rome, the most noteworthy are Santa Maria in Trastevere, St. John Lateran, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, San Saba, San Paolo fuori le Mura, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Santa Maria Maggiore, San Crisogono,[9] San Clemente, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, and the Sistine Chapel and the Stanza della Segnatura at the Vatican. Outside Rome, Tivoli, Subiaco, Anagni, Ferentino, Terracina and Tarquinia contain remarkable cosmatesque works. Also, Cosmati built innovative decoration for the Cathedral of Civita Castellana.

See also

Gallery

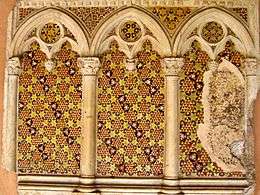

Cosmatesque decoration from the cloisters of San Paolo fuori le Mura, Rome.

Cosmatesque decoration from the cloisters of San Paolo fuori le Mura, Rome. Detail of Cosmatesque floor, from the central nave of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Detail of Cosmatesque floor, from the central nave of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. Detail of Cosmatesque floor, from the central nave of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Detail of Cosmatesque floor, from the central nave of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.- Detail of Cosmatesque floor, from Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome.

.jpg) Two columns with Cosmatesque ornament in the cloister of San Paolo fuori le Mura, Rome.

Two columns with Cosmatesque ornament in the cloister of San Paolo fuori le Mura, Rome.- Detail of Cosmatesque floor, in the Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

Detail of Cosmatesque floor, in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome.

Detail of Cosmatesque floor, in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome.- Cosmatesque floor, from the Chiesa di San Benedetto in Piscinula, in the Trastevere section of Rome.

Notes

- Maev Kennedy, 'Carpet of stone: medieval mosaic pavement revealed' , The Guardian, 5 May 2008

- BBC – The Culture Show – Cosmati Pavement

- Excerpted from A dictionary of architecture and building, biographical, historical, and descriptive by Russell Sturgis (1836–1909), published 1901 and out of copyright

- Paloma Pajares-Ayuela: Cosmatesque Ornament, W. W. Norton, 2002, p. 255

- A dictionary of architecture and building, p.691 Cosmati

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Cosmati Mosaic.

- Paloma Pajares-Ayuela: Cosmatesque Ornament, W. W. Norton, 2002, p. 30.

- Fawcett, Jane, Historic floors: their history and conservation, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998, ISBN 0-7506-2765-4, ISBN 978-0-7506-2765-8, Google books

- MIchela Cigola, Mosaici pavimentali cosmateschi. Segni, disegni e simboli, in "Palladio" Nuova serie anno VI n. 11, giugno 1993; pp. 101–110.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cosmatesque. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia article on Cosmati Mosaic

- Cosmatesque pavement of S. Maria in Cosmedin (with photographs)

- The Cosmati pavement at Westminster Abbey

- Encyclopaedia Britannica article on Cosmati work

![]()