Vascular access

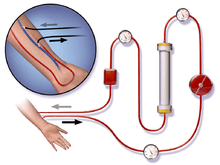

Vascular access refers to a rapid, direct method of introducing or removing devices or chemicals from the bloodstream. In hemodialysis, vascular access is used to remove the patient's blood so that it can be filtered through the dialyzer. Three primary methods are used to gain access to the blood: an intravenous catheter, an arteriovenous fistula (AV) or a synthetic graft. In the latter two, needles are used to puncture the graft or fistula each time dialysis is performed.

The type of vascular access created for patients on hemodialysis is influenced by factors such as the expected time course of a patient's kidney failure and the condition of his or her vasculature. Patients may have multiple accesses, usually because an AV fistula or graft is maturing and a catheter is still being used. The creation of all these three major types of vascular accesses requires surgery.[1]

Catheter

Catheter access, sometimes called a CVC (central venous catheter), consists of a plastic catheter with two lumens (or occasionally two separate catheters) which is inserted into a large vein (usually the vena cava, via the internal jugular vein or the femoral vein) to allow large flows of blood to be withdrawn from one lumen, to enter the dialysis circuit, and to be returned via the other lumen. However, blood flow is almost always less than that of a well functioning fistula or graft.

Catheters are usually found in two general varieties, tunnelled and non-tunnelled.[2]

Non-tunnelled catheter access is for short-term access (up to about 10 days, but often for one dialysis session only), and the catheter emerges from the skin at the site of entry into the vein.

Tunnelled catheter access involves a longer catheter, which is tunnelled under the skin from the point of insertion in the vein to an exit site some distance away. It is usually placed in the internal jugular vein in the neck and the exit site is usually on the chest wall. The tunnel acts as a barrier to invading microbes, and as such, tunnelled catheters are designed for short- to medium-term access (weeks to months only), because infection is still a frequent problem.

Aside from infection, venous stenosis is another serious problem with catheter access. The catheter is a foreign body in the vein and often provokes an inflammatory reaction in the vein wall. This results in scarring and narrowing of the vein, often to the point of occlusion. This can cause problems with severe venous congestion in the area drained by the vein and may also render the vein, and the veins drained by it, useless for creating a fistula or graft at a later date. Patients on long-term hemodialysis can literally 'run out' of access, so this can be a fatal problem.

Catheter access is usually used for rapid access for immediate dialysis, for tunnelled access in patients who are deemed likely to recover from acute kidney injury, and for patients with end-stage kidney failure who are either waiting for alternative access to mature or who are unable to have alternative access.

Catheter access is often popular with patients, because attachment to the dialysis machine doesn't require needles. However, the serious risks of catheter access noted above mean that such access should be contemplated only as a long-term solution in the most desperate access situation.

AV fistula

AV (arteriovenous) fistulas are recognized as the preferred access method. To create a fistula, a vascular surgeon joins an artery and a vein together through anastomosis. Since this bypasses the capillaries, blood flows rapidly through the fistula. One can feel this by placing one's finger over a mature fistula. This is called feeling for "thrill" and produces a distinct 'buzzing' feeling over the fistula. One can also listen through a stethoscope for the sound of the blood "whooshing" through the fistula, a sound called bruit.

Fistulas are usually created in the nondominant arm and may be situated on the hand (the 'snuffbox' fistula'), the forearm (usually a radiocephalic fistula, or so-called Brescia-Cimino fistula, in which the radial artery is anastomosed to the cephalic vein), or the elbow (usually a brachiocephalic fistula, where the brachial artery is anastomosed to the cephalic vein). Though less common, fistulas can also be created in the groin, though the creation process differs. Placement in the groin is usually done when options in the arm and hands are not available due to anatomy or the failure of fistulas previously created in the arms/hands. A fistula will take a number of weeks to mature, on average perhaps 4–6 weeks.

During treatment, two needles are inserted into the vein, one to draw blood and one to return it. The orientation of the needles takes the normal flow of the blood into account. The "arterial" needle draws blood from the "upstream" location while the "venous" needle returns blood "downstream". This sequence prevents partial recycling of the same blood through the dialysis machine, which would lead to less effective treatment.

The advantages of the AV fistula use are lower infection rates, because no foreign material is involved in their formation, higher blood flow rates (which translates to more effective dialysis), and a lower incidence of thrombosis. The complications are fewer than with other access methods. If a fistula has a very high blood flow and the vasculature that supplies the rest of the limb is poor, a steal syndrome can occur, where blood entering the limb is drawn into the fistula and returned to the general circulation without entering the limb's capillaries. This results in cold extremities of that limb, cramping pains, and, if severe, tissue damage. One long-term complication of an AV fistula can be the development of an aneurysm, a bulging in the wall of the vein where it is weakened by the repeated insertion of needles over time. To a large extent the risk of developing an aneurysm can be reduced by carefully rotating needle sites over the entire fistula, or using the "buttonhole" (constant site) technique. Aneurysms may necessitate corrective surgery and may shorten the useful life of a fistula. Fistulas can also become blocked due to blood clotting or infected if sterile precautions are not followed during needle insertion at the start of dialysis. Because of the high volume of blood flowing through the fistula, excessive bleeding can also occur. This is most common soon after a dialysis treatment. Pressure must be applied to the needle holes to induce clotting. If that pressure is removed prematurely or a patient engages in physical activity too soon after dialysis, the needle holes can open up.

To prevent damage to the fistula and aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm formation, it is recommended that the needle be inserted at different points in a rotating fashion. Another approach is to cannulate the fistula with a blunted needle, in exactly the same place. This is called a 'buttonhole' approach. Often two or three buttonhole places are available on a given fistula. This also can prolong fistula life and help prevent damage to the fistula.

A recent study that was published in The American Journal of Pathology, provides information about the mechanisms underlying failure of the most common type of hemodialysis vascular access, the arteriovenous fistula. In spite of AV Fistula being one of the most preferred methods of Vascular access, the researchers observed that, up to 60% of newly created fistulas never become usable for dialysis because they fail to mature (meaning the vessels do not enlarge enough to support the dialysis blood circuit.). This study suggests that, the impairment in responsiveness to nitric oxide that occurs in some patients with end-stage renal disease may result in hyperplasia (excessive growth) of the innermost layer of the blood vessels or reduced ability of the vessels to dilate. Either abnormality can limit the maturation and viability of the arteriovenous fistula. This research raises the possibility that therapeutic restoration of nitric oxide responsiveness through manipulation of local mediators may prevent fistula maturation failure in patients and potentially contribute to their ability to remain on hemodialysis.[3]

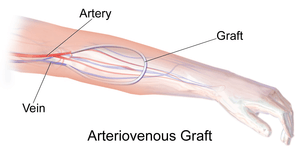

AV graft

AV (arteriovenous) grafts are much like fistulas in most respects, except that an artificial vessel is used to join the artery and vein. The graft usually is made of a synthetic material, often PTFE, but sometimes chemically treated, sterilized veins from animals are used. Grafts are inserted when the patient's native vasculature does not permit a fistula. They mature faster than fistulas, and may be ready for use several weeks after formation (some newer grafts may be used even sooner). However, AV grafts are at high risk to develop narrowing, especially in the vein just downstream from where the graft has been sewn to the vein. Narrowing often leads to thrombosis (clotting). As foreign material, they are at greater risk for becoming infected. More options for sites to place a graft are available, because the graft can be made quite long. Thus a graft can be placed in the thigh or even the neck (the 'necklace graft').

Fistula First project

AV fistulas have a much better access patency and survival than do venous catheters or grafts. They also produce better patient survival and have far fewer complications compared to grafts or venous catheters. For this reason, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) has set up a Fistula First Initiative,[4] whose goal is to increase the use of AV fistulas in dialysis patients. This initiative has had many successes, but fistula is not always the superior strategy when it comes to the elderly.[5]

There is ongoing research to make bio-engineered blood vessels, which may be of immense importance in creating AV fistulas for patients on hemodialysis, who do not have good blood vessels for creation of one. It involves growing cells which produce collagen and other proteins on a biodegradable micromesh tube followed by removal of those cells to make the 'blood vessels' storable in refrigerators.[6]

See also

References

- Kallenbach J.Z.In: Review of hemodialysis for nurses and dialysis personnel. 7th ed. St. Louis, Missouri:Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

- Frankel, A. (2006-04-01). "Temporary Access and Central Venous Catheters". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 31 (4): 417–422. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.10.003. PMID 16360326.

- "New research shows promise for improving vascular access for hemodialysis patients". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- Fistula First Initiative

- DeSilva, R. N.; Patibandla, B. K.; Vin, Y.; Narra, A.; Chawla, V.; Brown, R. S.; Goldfarb-Rumyantzev, A. S. (2013-08-01). "Fistula First Is Not Always the Best Strategy for the Elderly". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 24 (8): 1297–1304. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012060632. ISSN 1046-6673. PMC 3736704. PMID 23813216.

- Seppa, Nathan (2 February 2011). "Bioengineering Better Blood Vessels". Science News. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

External links