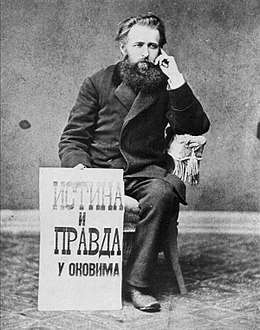

Vasa Pelagić

Vasilije "Vasa" Pelagić (Gornji Žabar, now Pelagićevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1833 – Požarevac, Serbia, 1899) was a Bosnian Serb writer, physician, educator, clergyman, nationalist and a proponent of utopian socialism among the Serbs in the second half of the nineteenth century.[1] Today he is considered one of the first theoreticians of physical education in the Balkans. He is also remembered as a revolutionary democrat and one of the leaders of the national liberation and socialist movement in Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Vasa Pelagić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1833 Gornji Žabar, now Pelagićevo |

| Died | 1899 |

| Other names | Vasilije Pelagić |

| Occupation | Politician |

Biography

Born into a middle-class Serb family, Pelagić was educated at a high school (gymnasium) in Sarajevo and went on to pursue further studies at the Grandes écoles in Belgrade, graduating from the Faculty of Theology in 1857. In 1860 he served as teacher in Brčko where he founded a Serbian reading room, one of the first in Bosnia. From there, via Belgrade, he went to Russia for his post-graduate studies. At the Moscow State University, he attended lectures in political issues facing medicine and history of medicine, from 1863 to 1865. He returned to Bosnia where he served in Banja Luka as an archimandrite and rector of a newly founded Serbian Orthodox Seminary. There he preached progressive ideas and taught gymnastics. His world view was greatly influenced not only by the Russian Revolutionary Democrats but by the decline of the vassal and tributary states of the Ottoman Empire.

Brooding upon what he saw as the humiliation of his native land by Turkish sultans and later by Habsburg monarchs, Pelagić conceived the idea of restoring the spirits of his countrymen by the development of their physical and moral powers through the practice of gymnastics. He wrote pamphlets and books which brought together his study of the attitudes of the ancients toward diet, exercise and hygiene, and the use of natural methods for the cure of diseases. He also explained the principles of physical therapy and his Narodni lekar (People's Physician) is considered the first Serbian book on sports medicine. Young gymnasts would regard themselves as members of a kind of guild for the emancipation of their homeland.

Exile in Asia Minor

The authorities finally realized Pelagić aimed at establishing a united Serbia, and that his school was a political and liberal club. The conflict resulted in the closing of the Seminary in 1869 and Pelagić's arrest on grounds (among other charges) that he taught gymnastics. For the Turks, gymnastics evidently seemed to bear a keen resemblance to military exercises. Kept in semi-confinement successively at the metropolitan's residence in Sarajevo, he was finally sentenced to exile and imprisonment for many years.

He spent more than two years in confinement, first he was taken from a Sarajevo prison to northwestern Anatolia in what is now Turkey. From Troy he was transferred to Balikesir in the Marmara region, then back northwestern Anatolia, but this time in Bursa, and finally at the end to Kutahya, where he spent a little more than a year. With the help of the Serbian (Filip Hristić) and Russian (Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev) ambassadors in Constantinople, Pelagić succeeded, however, in effecting his escape and reached Serbia in 1871 where he assisted in the organization of the Serbian Liberal Youth Movement, known as Omladina, and then lead their congress in Vršac. From there he went to Cetinje and assisted in the organization of the Association for Serb Liberation and Unification with Milan Kostić, Jovan Sundečić, Miša Dimitijević and many other prominent Serbian intellectuals. There he came into conflict with Prince Nicholas I of Montenegro who did not want to compromise his relations with Russia and other empires. In 1872 he left Cetinje for Novi Sad, Graz, Prague, Trieste and Zurich. Upon his return, he decided to publicly reject his monastic title of archimandrite and in the Serbian liberal journal Zastava (Flag) on 29 April (17 Julian Calendar) 1873 he announced his decision. From then on he became one of the most famous dissenters and anti-clerical activists in the Balkans.

Uprising in Bosnia

Pelagić took part in the anti-Turkish uprising of 1875–78 in Bosnia and vigorously protested the occupation of these territories by Austria-Hungary three years later (1878). The rebellion preparations started later than the Herzegovinian, and the actions of the two regions were not coordinated. Among the organizers and leaders were Vaso Vidović (1840-1925), Simo Bilbija, Jovo Bilbija, Spasoje Babić and Vasa Pelagić. During the 1875 uprisings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there was a leftist trend that championed a social programme. It was led by Pelagić and enjoyed the support of journalist-anarchists such as Manojlo Ervaćanin (1849–1909), a prominent figure in the Serbian liberation movement and member of the Bakuninist Slavonic Section, Kosta Ugrinić (1848–1933), Pera Matanović, Djoka Vlajković (1831-1883), Jevrem Marković (1839-1878), Vladimir Jovanović, and others. Many Italian anarchists were involved in the uprisings (Errico Malatesta himself making two attempts to enter Bosnia-Herzegovina), as well as anarchists from Russia and other parts of Europe. Early in 1875 Pelagić took an active part in the formation of a Free Corps, a volunteer force in the Bosnian rebel army. He commanded a battalion of the corps, though he was often employed in the secret service during the same period.

In the 1890s Pelagić helped organize labor societies among artisans and workers which he believed would become the basis for a Serbian socialist party. With a group of like-minded Serbian intellectuals, Pelagić helped found the Belgrade newspaper Socijal-Demokrat in 1895. In his works he advocated socialism and materialist views on the development of nature.

Last years

After the war he returned to Belgrade where he was appointed state teacher of gymnastics, and took on a role in the formation of the student patriotic fraternities, promoting physical fitness. A man of populistic nature, rugged, eccentric and outspoken, Pelagić often came into conflict with politicians and clerics. Late in life, Pelagić was incarcerated for his anarchistic writings in Požarevac, where he suddenly died.

Legacy

Vasa Pelagić's influence on the development of physical education and sports in Serbia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina was of great significance. Because of his theoretical and practical work, most of all in the school of physical education he is classified as one of the most important personalities from Bosnia and Herzegovina from that particular era, and within the area of physical culture. He also gave a great significance to the development of theory of physical exercise, physical education in schools, promoted games and other sport activities. He was a first theoretician and a pioneer of modern theory of physical culture in Bosnia and Serbia. Pelagić's role was creating and developing the theory of physical culture in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia.

During the thirty years of his revolutionary life and lengthy prison terms Pelagić managed to publish numerous books, pedagogic treatises and books aimed at educating people, which brought him fame as "the people's teacher". Vasa Pelagić's Narodni učitelj ("People's Teacher") was from 1879 until 1894 published in four editions in circulation of 18,000, while all his other books and booklets reached the circulation of 212,000 before his death, which made him probably the most widely read Serbian writer.[2] Alongside a vehement anti-clericalism his books spread early socialist ideas.

Works

- Pokušaji za narodno i lično unaprećenje (Belgrade, 1871).

- Put srećnijem životu ili nova nauka i novi ljudi (Budapest, 1879).

- Socijalizam ili osnovni preporoćaj društva (Belgrade, 1894).

- Istorija bosansko-hercegovačke bune (Sarajevo, 1893).

References

- Roumen Daskalov, Diana Mishkova (2013). "Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Two". Brill. p. 233.

- Risto Besarović, "Vasa Pelagić", p. 190

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vaso Pelagić. |

2. Biography adapted from Serbian Wikipedia:https://sr.wikipedia.org/sr/%D0%92%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%BE_%D0%9F%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%B8%D1%9B