Vadomarius

Vadomarius (German: Vadomar) was an Alemannic king and Roman general, who shared power with his brother Gundomadus. After instigating an indecisive campaign in Gaul against the Romans, Vadomarius and his brother signed a treaty with the Roman emperor Constantius II in AD 356. Encouraged by Constantius II, Vadomarius employed his Alemanni forces in an attack against Julian (Constantius' Caesar who had revolted against his rule). Vadomarius then concluded a treaty with Julian, after which, he unsuccessfully attempted to play the two Roman figures against one another. When Julian was made aware of this, he arrested Vadomarius and banished him to Hispania. His son Vithicabius succeeded him as king. Later, Vadomarius allied himself with Rome under emperors Jovian and Valens, leading his forces against the usurper Procopius and fighting the Persians on Rome's behalf.

Life

The life of Vadomarius is best documented by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus. According to his writings, Constantius II explicitly went to Valentia to wage war against Vadomarius and Gundomadus, whose forces had been laying waste to parts of Gaul.[1] In 356, Vadomarius and his brother Gundomadus concluded a peace treaty with the Romans after having lost a battle against emperor Constantius II.[2]

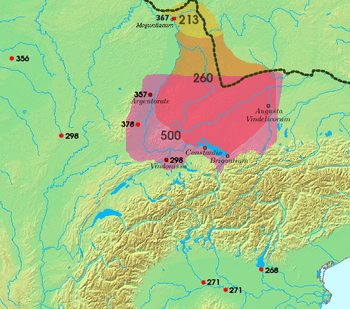

After Gundomadus was treacherously killed by his own people in 357, the Alemanni rallied themselves under Vadomarius, while remaining an ally of Constantius II.[3] Julian's rise to power and Vadomarius' decision to stand by Constantius II was likely the result of intimidation, which subsequently led him to join and lead the Alamannic coalition in AD 357.[4] It is possible that Vadomarius even may have supplied troops to fight against other Germanic tribesman during the Battle of Strasbourg.[4] The evidence for this stems from the fact that he continued acting as an agent of Constantius II in sorting out the mess following the battle—meanwhile, he also kept an eye on Julian.[4] In this regard, historian John F. Drinkwater argues that "Vadomarius should be regarded as Roman."[4] Constantius II even granted Vadomarius and the Alemanni rights to settle along the western bank of the Rhine.[5] Seeking to use the Alemanni against Julian the Apostate, Constantius II then incited the Germanic Alemanni to march upon his erstwhile competitor in the East, having established trust with them.[6] However, Julian's military power was greater than expected and in 359, he crossed the Rhine near Mainz with his forces and scattered his enemies; thereafter he concluded peace treaties with the Alemannic kings Vadomarius, Macrian, Hariobaudes, Urius, Ursicinus and Vestralpus.[7]

In 360, Vadomarius attacked areas along the border of Tyrol, which greatly grieved Julian since it violated the recent treaty.[8] Vadomarius was carrying out these raids along the borders areas per the urging of Constantius II, which were outlined in letters between the two.[9] When Julian learned of these messages, he was incensed and invited Vadomarius to a banquet, at which he was arrested and placed under guard.[10][6] Vadomarius was subsequently banished to Spain.[11]

After being a Spain for a brief period, Vadomarius then had a distinguished career in the Roman army,[12] rising to the position of dux of Phoenice.[13] Under emperor Valens, Vadomarius employed siege-warfare techniques he would have learned as a Roman soldier to besiege the supporters of the usurper Procopius in Nicaea.[14] He is last heard from fighting against the Persians in Mesopotamia in 371.[13] Vadomarius was succeeded as king by his son Vithicabius, who much like his father, was considered a threat to Rome.[15] The emperor Gratian had Vithicabius murdered when his loyalty to the Roman throne "became suspect."[16] The story of both Vadomarius and his son reveal the manner in which Romans handled their barbarian neighbors, co-opting and recruiting them when it suited their needs but against whom they often used treacherous means.[17]

See also

References

Citations

- Marcellinus 1894, p. 32, [14.10.1].

- Bunson 1995, p. 434.

- Marcellinus 1894, p. 111, [16.12.17–18].

- Drinkwater 2007, p. 156.

- Goldsworthy 2009, p. 216.

- Burns 2003, p. 338.

- Marcellinus 1894, pp. 163–165, [18.2.12–19].

- Marcellinus 1894, pp. 246–247, [21.3.1].

- Marcellinus 1894, p. 247–248, [21.3.4–5].

- Marcellinus 1894, p. 248, [21.3.6].

- Marcellinus 1894, p. 248, [21.4.6].

- Goldsworthy 2019, p. 167.

- James 2014, p. 42.

- Burns 1994, p. 5.

- Heather 2005, p. 90.

- Goldsworthy 2009, p. 273.

- Burns 2003, p. 339.

Bibliography

- Burns, Thomas (1994). Barbarians within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, CA. 375–425 A.D. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25331-288-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, Thomas (2003). Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.—A.D. 400. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80187-306-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19510-233-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drinkwater, John F. (2007). The Alamanni and Rome 213-496 (Caracalla to Clovis). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-29568-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30013-719-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2019). Roman Warfare. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-54169-923-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19515-954-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Edward (2014). Europe's Barbarians, AD 200–600. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-58277-296-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marcellinus, Ammianus (1894). The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus. Translated by C.D. Yonge. London: George Bell & Sons. OCLC 681127910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Thorsten Fischer: Vadomarius. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2. Auflage. Band 35, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-018784-7, S. 322–326.

- Dieter Geuenich: Die alemannischen Breisgaukönige Gundomadus und Vadomarius. In: Sebastian Brather, Dieter Geuenich, Christoph Huth (Hrsg.): Historia archaeologica. Festschrift für Heiko Steuer zum 70. Geburtstag (= Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde. Ergänzungsbände. Band 70). de Gruyter, Berlin u. a. 2009, ISBN

- Dieter Geuenich: Geschichte der Alemannen (= Kohlhammer-Urban-Taschenbücher. 575). 2., überarbeitete Auflage. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-17-018227-7.