Positive airway pressure

Positive airway pressure (PAP) is a mode of respiratory ventilation used in the treatment of sleep apnea. PAP ventilation is also commonly used for those who are critically ill in hospital with respiratory failure, in newborn infants (neonates), and for the prevention and treatment of atelectasis in patients with difficulty taking deep breaths. In these patients, PAP ventilation can prevent the need for tracheal intubation, or allow earlier extubation. Sometimes patients with neuromuscular diseases use this variety of ventilation as well. CPAP is an acronym for "continuous positive airway pressure", which was developed by Dr. George Gregory and colleagues in the neonatal intensive care unit at the University of California, San Francisco.[1] A variation of the PAP system was developed by Professor Colin Sullivan at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, Australia, in 1981.[2]

| Positive airway pressure | |

|---|---|

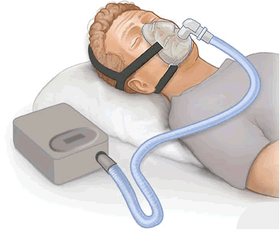

CPAP therapy: flow generator, hose, orinasal mask | |

| Specialty | pulmonary |

The main difference between BiPAP and CPAP machines is that BiPAP machines have two pressure settings: the prescribed pressure for inhalation (ipap), and a lower pressure for exhalation (epap). The dual settings allow the patient to get more air in and out of their lungs.

Medical uses

The main indications for positive airway pressure are congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. There is some evidence of benefit for those with hypoxia and community acquired pneumonia.[3]

PAP ventilation is often used for patients who have acute type 1 or 2 respiratory failure. Usually PAP ventilation will be reserved for the subset of patients for whom oxygen delivered via a face mask is deemed insufficient or deleterious to health (see CO

2 retention). Usually, patients on PAP ventilation will be closely monitored in an intensive care unit, high-dependency unit, coronary care unit or specialist respiratory unit.

The most common conditions for which PAP ventilation is used in hospital are congestive cardiac failure and acute exacerbation of obstructive airway disease, most notably exacerbations of COPD and asthma. It is not used in cases where the airway may be compromised, or consciousness is impaired. CPAP is also used to assist premature babies with breathing in the NICU setting.

The mask required to deliver CPAP must have an effective seal, and be held on very securely. The "nasal pillow" mask maintains its seal by being inserted slightly into the nostrils and being held in place by various straps around the head. Some full-face masks "float" on the face like a hover-craft, with thin, soft, flexible "curtains" ensuring less skin abrasion, and the possibility of coughing and yawning. Some people may find wearing a CPAP mask uncomfortable or constricting: eyeglass wearers and bearded men may prefer the nasal-pillow type of mask. Breathing out against the positive pressure resistance (the expiratory positive airway pressure component, or EPAP) may also feel unpleasant to some patients. These factors lead to inability to continue treatment due to patient intolerance in about 20% of cases where it is initiated.[4] Some machines have pressure relief technologies that makes sleep therapy more comfortable by reducing pressure at the beginning of exhalation and returning to therapeutic pressure just before inhalation. The level of pressure relief is varied based on the patient’s expiratory flow, making breathing out against the pressure less difficult.[5] Those who suffer an anxiety disorder or claustrophobia[6] are less likely to tolerate PAP treatment. Sometimes medication will be given to assist with the anxiety caused by PAP ventilation.

Unlike PAP used at home to splint the tongue and pharynx, PAP is used in hospital to improve the ability of the lungs to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide, and to decrease the work of breathing (the energy expended moving air into and out of the alveoli). This is because:

- During inspiration, the inspiratory positive airway pressure, or IPAP, forces air into the lungs—thus less work is required from the respiratory muscles.

- The bronchioles and alveoli are prevented from collapsing at the end of expiration. If these small airways and alveoli are allowed to collapse, significant pressures are required to re-expand them. This can be explained using the Young–Laplace equation (which also explains why the hardest part of blowing up a balloon is the first breath).

- Entire regions of the lung that would otherwise be collapsed are forced and held open. This process is called recruitment. Usually these collapsed regions of lung will have some blood flow (although reduced). Because these areas of lung are not being ventilated, the blood passing through these areas is not able to efficiently exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. This is called ventilation–perfusion (or V/Q) mismatch. The recruitment reduces ventilation–perfusion mismatch.

- The amount of air remaining in the lungs at the end of a breath is greater (this is called the functional residual capacity). The chest and lungs are therefore more expanded. From this more expanded resting position, less work is required to inspire. This is due to the non-linear compliance–volume curve of the lung.

Common non-Continuous positive airway pressure device.

Common non-Continuous positive airway pressure device.

Disadvantages

A major issue with CPAP is non-adherence. Studies showed that some users either abandon the use of CPAP, and/or use CPAP for only a fraction of the nights.[7][8]

Prospective PAP candidates are often reluctant to use this therapy, since the nose mask and hose to the machine look uncomfortable and clumsy. Airflow required for some patients can be vigorous. Some patients will develop nasal congestion while others may experience rhinitis or a runny nose.[9] Some patients adjust to the treatment within a few weeks, others struggle for longer periods, and some discontinue treatment entirely. However, studies show that cognitive behavioral therapy at the beginning of therapy dramatically increases adherence—by up to 148%.[10] While common PAP side effects are merely nuisances, serious side effects such as eustachian tube infection, or pressure build-up behind the cochlea are very uncommon. Furthermore, research has shown that PAP side effects are rarely the reason patients stop using PAP.[11] There are reports of dizziness, sinus infections, bronchitis, dry eyes, dry mucosal tissue irritation, ear pain, and nasal congestion secondary to CPAP use.[12]

PAP manufacturers frequently offer different models at different price ranges, and PAP masks have many different sizes and shapes, so that some users need to try several masks before finding a good fit. These different machines may not be comfortable for all users, so proper selection of PAP models may be very important in furthering adherence to therapy.

Beards, mustaches, or facial irregularities may prevent an air-tight seal. Where the mask contacts the skin must be free from dirt and excess chemicals such as skin oils. Shaving before mask-fitting may be necessary in some cases. However, facial irregularities of this nature frequently do not hinder the operation of the device or its positive airflow effects for sleep apnea patients. For many people, the only problem from an incomplete seal is a higher noise level near the face from escaping air.

The CPAP mask can act as an orthodontic headgear and move the teeth and the upper and/or lower jaw backward. This effect can increase over time and may or may not cause TMJ disorders in some patients. These facial changes have been dubbed "Smashed Face Syndrome".[13]

Mechanism of action

Continuous pressure devices

Fixed-pressure CPAP

A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine was initially used mainly by patients for the treatment of sleep apnea at home, but now is in widespread use across intensive care units as a form of ventilation. Obstructive sleep apnea occurs when the upper airway becomes narrow as the muscles relax naturally during sleep. This reduces oxygen in the blood and causes arousal from sleep. The CPAP machine stops this phenomenon by delivering a stream of compressed air via a hose to a nasal pillow, nose mask, full-face mask, or hybrid, splinting the airway (keeping it open under air pressure) so that unobstructed breathing becomes possible, therefore reducing and/or preventing apneas and hypopneas.[14][15] It is important to understand, however, that it is the air pressure, and not the movement of the air, that prevents the apneas. When the machine is turned on, but prior to the mask being placed on the head, a flow of air comes through the mask. After the mask is placed on the head, it is sealed to the face and the air stops flowing. At this point, it is only the air pressure that accomplishes the desired result. This has the additional benefit of reducing or eliminating the extremely loud snoring that sometimes accompanies sleep apnea.

The CPAP machine blows air at a prescribed pressure (also called the titrated pressure). The necessary pressure is usually determined by a sleep physician after review of a study supervised by a sleep technician during an overnight study (polysomnography) in a sleep laboratory. The titrated pressure is the pressure of air at which most (if not all) apneas and hypopneas have been prevented, and it is usually measured in centimetres of water (cmH

2O). The pressure required by most patients with sleep apnea ranges between 6 and 14 cmH

2O. A typical CPAP machine can deliver pressures between 4 and 20 cmH

2O. More specialised units can deliver pressures up to 25 or 30 cmH

2O.

CPAP treatment can be highly effective in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. For some patients, the improvement in the quality of sleep and quality of life due to CPAP treatment will be noticed after a single night's use. Often, the patient's sleep partner also benefits from markedly improved sleep quality, due to the amelioration of the patient's loud snoring.

Given that sleep apnea is a chronic health issue which commonly doesn't go away, ongoing care is usually needed to maintain CPAP therapy. Based on the study of cognitive behavioral therapy (referenced above), ongoing chronic care management is the best way to help patients continue therapy by educating them on the health risks of sleep apnea and providing motivation and support.

Automatic positive airway pressure

An automatic positive airway pressure device (APAP, AutoPAP, AutoCPAP) automatically titrates, or tunes, the amount of pressure delivered to the patient to the minimum required to maintain an unobstructed airway on a breath-by-breath basis by measuring the resistance in the patient's breathing, thereby giving the patient the precise pressure required at a given moment and avoiding the compromise of fixed pressure.

Bi-level pressure devices

"VPAP" or "BPAP" (variable/bilevel positive airway pressure) provides two levels of pressure: inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and a lower expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) for easier exhalation. (Some people use the term BPAP to parallel the terms APAP and CPAP.) Often BPAP is incorrectly referred to as "BiPAP". However, BiPAP is the name of a portable ventilator manufactured by Respironics Corporation; it is just one of many ventilators that can deliver BPAP.[16]

- Modes

- S (Spontaneous) – In spontaneous mode the device triggers IPAP when flow sensors detect spontaneous inspiratory effort and then cycles back to EPAP.

- T (Timed) – In timed mode the IPAP/EPAP cycling is purely machine-triggered, at a set rate, typically expressed in breaths per minute (BPM).

- S/T (Spontaneous/Timed) – Like spontaneous mode, the device triggers to IPAP on patient inspiratory effort. But in spontaneous/timed mode a "backup" rate is also set to ensure that patients still receive a minimum number of breaths per minute if they fail to breathe spontaneously.

Expiratory positive airway pressure devices

Nasal expiratory positive airway pressure (Nasal EPAP) is a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and snoring.[17][18]

Contemporary EPAP devices have two small valves that allow air to be drawn in through each nostril, but not exhaled; the valves are held in place by adhesive tabs on the outside of the nose.[17] The mechanism by which EPAP may work is not clear; it may be that the resistance to nasal exhalation leads to a buildup in CO

2 which in turn increases respiratory drive, or that resistance to exhalation generates pressure that forces the upper airway to open wider.[17]

Components

- Flow generator (PAP machine) provides the airflow

- Hose connects the flow generator (sometimes via an in-line humidifier) to the interface

- Interface (nasal or full face mask, nasal pillows, or less commonly a lip-seal mouthpiece) provides the connection to the user's airway

Optional features

- Humidifier adds moisture to low humidity air

- Heated: Heated water chamber that can increase patient comfort by eliminating the dryness of the compressed air. The temperature can usually be adjusted or turned off to act as a passive humidifier if desired. In general, a heated humidifier is either integrated into the unit or has a separate power source (i.e. plug).

- Passive: Air is blown through an unheated water chamber and is dependent on ambient air temperature. It is not as effective as the heated humidifier described above, but still can increase patient comfort by eliminating the dryness of the compressed air. In general, a passive humidifier is a separate unit and does not have a power source.

- Mask liners: Cloth-based mask liners may be used to prevent excess air leakage and to reduce skin irritation and dermatitis.

- Ramp may be used to temporarily lower the pressure if the user does not immediately sleep. The pressure gradually rises to the prescribed level over a period of time that can be adjusted by the patient and/or the DME provider.

- Exhalation pressure relief: Gives a short drop in pressure during exhalation to reduce the effort required. This feature is known by the trade name C-Flex or A-Flex in some CPAPs made by Respironics and EPR in ResMed machines.

- Flexible chin straps may be used to help the patient not breathe through the mouth (full-face masks avoid this problem), thereby keeping a closed pressure system. The straps are elastic enough that the patient can easily open his mouth if he feels that he needs to. Modern straps use a quick-clip instant fit. Velcro-type adjustments allow quick sizing, before or after the machine is turned on.

- Data logging records basic compliance info or detailed event logging, allowing the sleep physician (or patient) to download and analyse data recorded by the machine to verify treatment effectiveness.

- Automatic altitude adjustment versus manual altitude adjustment.

- DC power source versus AC power source.

Such features generally increase the likelihood of PAP tolerance and compliance.[10]

Care and maintenance

As with all durable medical equipment, proper maintenance is essential for proper functioning, long unit life and patient comfort. The care and maintenance required for PAP machines varies with the type and conditions of use, and are typically spelled out in a detailed instruction manual specific to the make and model.

Most manufacturers recommend that the end user perform daily and weekly maintenance. Units must be checked regularly for wear and tear and kept clean. Poorly connected, worn or frayed electrical connections may present a shock or fire hazard; worn hoses and masks may reduce the effectiveness of the unit. Most units employ some type of filtration, and the filters must be cleaned or replaced on a regular schedule. Sometimes HEPA filters may be purchased or modified for asthma or other allergy clients. Hoses and masks accumulate exfoliated skin, particulate matter, and can even develop mold. Humidification units must be kept free of mold and algae. Because units use substantial electrical power, housings must be cleaned without immersion. For humidification units, cleaning of the water container is imperative for several reasons. First, the container may build up minerals from the local water supply which eventually may be become part of the air breathed. Second, the container may eventually show signs of "sludge" coming from dust and other particles which make their way through the air filter which must also be changed as it accumulates dirt. To help clean the unit, some patients have used a very small amount of hydrogen peroxide mixed with the water in the container. They would then let it stand for a few minutes before emptying and rinsing. If this procedure is used, it is imperative to rinse the unit with soap and water before reinstalling onto the machine and breathing. Anti-bacterial soap is not recommended by sellers. To reduce the risk of contamination, distilled water is a good alternative to tap water. If traveling in areas where the mineral content or purity of the water is unknown or suspect, an alternative is to use a water "purifier" such as Brita. In cold climates, humidified air may require insulated and/or heated air hoses. These may be bought ready-made, or modified from commonly available materials.

Automated activated oxygen (ozone) cleaners are becoming more popular as a preferred maintenance method. However, the biological effects of using ozone as a PAP cleaning method has not scientifically been proven to provide a benefit to PAP users.

Portability

Since continuous compliance is an important factor in the success of treatment, it is of importance that patients who travel have access to portable equipment. Progressively, PAP units are becoming lighter and more compact, and often come with carrying cases. Dual-voltage power supplies permit many units to be used internationally.

Long-distance travel or camping presents special considerations. Most airport security inspectors have seen the portable machines, so screening rarely presents a special problem. Increasingly, machines are capable of being powered by the 400-Hz power supply used on most commercial aircraft and include manual or automatic altitude adjustment. Machines may easily fit on a ventilator tray on the bottom or back of a power wheelchair with an external battery. Some machines allow power-inverter and/or car-battery powering.

A limited study in Amsterdam in January 2016 using an induced sleep patient and when awake whilst on CPAP stretched the pectoralis major frontal chest muscles to bring back the shoulders and expand the chest and noted an increase in blood oxygen levels of over 6% during the manual therapy and 5% thereafter. The conclusion by Palmer was that the manual stretching of the pectoralis major combined at the time of the maximum inflation of CPAP allowed the permanent increase in blood oxygen levels and reinflation of collapsed alveoli. Further studies are required.

Some patients on PAP therapy also use supplementary oxygen. When provided in the form of bottled gas, this can present an increased risk of fire and is subject to restrictions. (Commercial airlines generally forbid passengers to bring their own oxygen.) As of November 2006, most airlines permit the use of oxygen concentrators.

Availability

In many countries, PAP machines are only available by prescription. A sleep study at an accredited sleep lab is usually necessary before treatment can start. This is because the pressure settings on the PAP machine must be tailored to a patient's treatment needs. A sleep medicine doctor, who may also be trained in respiratory medicine, psychiatry, neurology, paediatrics, family practice or otolaryngology (ear, nose and throat), will interpret the results from the initial sleep study and recommend a pressure test. This may be done in one night (a split study with the diagnostic testing done in the first part of the night, and CPAP testing done in the later part of the night) or with a follow up second sleep study during which the CPAP titration may be done over the entire night. With CPAP titration (split night or entire night), the patient wears the CPAP mask and pressure is adjusted up and down from the prescribed setting to find the optimal setting. Studies have shown that split-night protocol is an effective protocol for diagnosing OSA and titrating CPAP. CPAP compliance rate showed no difference between the split-night and the two-night protocols.[19]

- In the United States, PAP machines are often available at large discounts online, but a patient purchasing a PAP personally must handle the responsibility of securing reimbursement from his or her insurance or Medicare. Many of the internet providers that deal with insurance such as Medicare will provide upgraded equipment to a patient even if he or she only qualifies for a basic PAP. In some locations a government program, separate from Medicare, can be used to claim a reimbursement for all or part of the cost of the PAP device.

- In the United Kingdom, PAP machines are available on National Health Service prescription after a diagnosis of sleep apnea or privately from the internet provided a prescription is supplied.

- In Australia, PAP machines can be bought from the Internet or physical stores. There is no requirement for a doctor's prescription, however many suppliers will require a referral. Low-income earners who hold a Commonwealth Health Care Card should enquire with their state's health department about programmes that provide free or low-cost PAP machines. Those who have private health insurance may be eligible for a partial rebate on the cost of a CPAP machine and the mask. Superannuation may be released for the purchase of essential medical equipment such as PAP machines, on the provision of letters from two doctors, one of whom must be a specialist, and an application to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA).

- In Canada, CPAP units are widely available in all provinces. Funding for the therapy varies from province to province. In the province of Ontario, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care's Assistive Devices Program will fund a portion of the cost of a CPAP unit based on a sleep study in an approved sleep lab showing Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and the signature of an approved physician on the application form. This funding is available to all residents of Ontario with a valid health card.[20]

References

- Gregory GA; Kitterman JA; Phibbs RH; Tooley WH; Hamilton WK (1971). "Treatment of the idiopathic respiratory-distress syndrome with continuous positive airway pressure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 284 (24): 1333–40. doi:10.1056/NEJM197106172842401. PMID 4930602.

- "Sleepfoundation.com". Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- Cosentini R, Brambilla AM, Aliberti S, et al. (July 2010). "Helmet continuous positive airway pressure vs oxygen therapy to improve oxygenation in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized, controlled trial". Chest. 138 (1): 114–20. doi:10.1378/chest.09-2290. PMID 20154071.

Luo Y, Luo Y, Li Y, Zhou L, Zhu Z, Chen Y, Huang Y, Chen X (July 2016). "Helmet CPAP Versus Oxygen Therapy in Hypoxemic Acute Respiratory Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Yonsei Med J. 57 (4): 936–941. doi:10.3349/ymj.2016.57.4.936. PMC 4951471. PMID 27189288. - Dunn, Robert (2010). The Emergency Medicine Manual. Venom. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-9578121-6-1.

- "C-Flex Pressure Relief Technology". Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- "Sleep apnea". University of Maryland Medical Center – In-Depth Patient Education Reports. A.D.A.M. 2006-07-19. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- Rueda, A.D.; Santos-Silva, R.; Togeiro, S.M.; Tufik, S.; Bittencourt, L.R.A. (2009). "Improving CPAP compliance by a basic educational program with nurse support for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients". Sleep Science. 2 (1): 8–13. ISSN 1984-0063.

- Collen J, Lettieri C, Kelly W, Roop S (2009). "Clinical and polysomnographic predictors of short-term continuous positive airway pressure compliance". Chest. 135 (3): 704–9. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2182. PMID 19017888.

- "Effectiveness of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) in obstructive sleep apnoea in adults" (PDF). National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. 2000-02-20. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Richards D, Bartlett DJ, Wong K, Malouff J, Grunstein RR (May 2007). "Increased adherence to CPAP with a group cognitive behavioral treatment intervention: a randomized trial". Sleep. 30 (5): 635–40. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.5.635. PMID 17552379.

- Atwood, Charles W. "Sleep and CPAP Adherence". Ask The Expert. National Sleep Foundation.

- Ayow TM, Paquet F, Dallaire J, Purden M, Champagne KA (2009). "Factors influencing the use and nonuse of continuous positive airway pressure therapy: a comparative case study". Rehabil Nurs. 34 (6): 230–6. doi:10.1002/j.2048-7940.2009.tb00255.x. PMID 19927850.

- Tsuda H, Almeida FR, Tsuda T, Moritsuchi Y, Lowe AA (Oct 2010). "Craniofacial changes after 2 years of nasal continuous positive airway pressure use in patients with obstructive sleep apnea". Chest. 138 (4): 870–4. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0678. PMID 20616213.

- "Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea". WebMD. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "Different Types of Positive Airway Pressure Devices". SnoringHQ. 2015-02-08. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- C. Hormann; M. Baum; C. Putensen; N. J. Mutz; H. Benzer (January 1994). "Biphasic positive airway pressure (BIPAP)--a new mode of ventilatory support". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 11 (1): 37–42. PMID 8143712.

- Wu, H; Yuan, X; Zhan, X; Li, L; Wei, Y (September 2015). "A review of EPAP nasal device therapy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 19 (3): 769–74. doi:10.1007/s11325-014-1057-y. PMID 25245174.

- Riaz, M; et al. (2015). "Nasal Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure Devices (Provent) for OSA: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Sleep Disorders. 2015: 734798. doi:10.1155/2015/734798. PMC 4699057. PMID 26798519.

- BaHammam AS, ALAnbay E, Alrajhi N, Olaish AH (2015). "The success rate of split-night polysomnography and its impact on continuous positive airway pressure compliance". Ann Thorac Med. 10 (4): 274–8. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.160359. PMC 4652294. PMID 26664566.→

- "ADP: Continuous/Autotitrating Positive Pressure Systems". Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Archived from the original on 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-08-12.