Uta-awase

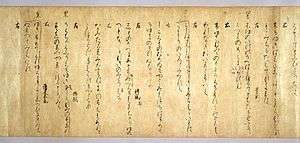

Uta-awase (歌合 or 歌合せ, sometimes romanized utaawase), poetry contests or waka matches, are a distinctive feature of the Japanese literary landscape from the Heian period. Significant to the development of Japanese poetics, the origin of group composition such as renga, and a stimulus to approaching waka as a unified sequence and not only as individual units, the lasting importance of the poetic output of these occasions may be measured also from their contribution to the imperial anthologies: 92 poems of the Kokinshū and 373 of the Shin Kokinshū were drawn from uta-awase.[1][2][3]

Social context

Mono-awase (物合), the matching of pairs of things by two sides, was one of the pastimes of the Heian court. The items matched might be paintings (絵合, e-awase), shells (貝合, kai-awase), sweet flag or iris roots, flowers, or poems.[4][5][6] The last took on new seriousness at the end of the ninth century with the Poetry Contest held by the Empress in the Kampyō era (寛平御時后宮歌合), the source of over fifty poems in the Kokinshū.[1][6]

The twenty-eight line diary of the Teijiin Poetry Contest (亭子院歌合) devotes two of its lines to the musical accompaniments, gagaku and saibara, and four to the costumes worn by the former emperor, other participants and the attendants who carried in the suhama (州浜), the trays with low miniature "sand-bar beach" coastal landscapes used in mono-awase. At the end of the contest, the poems were arranged around the suhama, those about mist being placed in the hills, those on the bush-warbler upon a blossoming bough, those on the cuckoo upon sprigs of unohana, and the remainder onto braziers hanging from miniature cormorant-fishing boats.[1][2]

Format

Elements common to uta-awase were a sponsor; two sides of contestants (方人, kataudo), the Left and the Right, the former having precedence, and usually the poets; a series of rounds (番, ban) in which a poem from each side was matched; a judge (判者, hanja) who declared a victory (勝, katsu) or a draw (持, ji), and might add comments (判詞, hanshi); and the provision of set topics (題, dai), whether handed out at the beginning or distributed in advance.[1] In general, anything that might introduce a discordant tone was avoided, while the evolving rules were 'largely prohibitive rather than prescriptive', admissible vocabulary largely limited to that of the Kokinshū, with words from the Man'yōshū liable to be judged archaism.[7] Use of a phrase such as harugasumi, 'in the spring haze', when the topic was the autumnal 'first geese' could provoke much hilarity.[7] The number of rounds varied by the occasion; The Poetry Contest in 1500 Rounds (千五百番歌合) of 1201 was the longest of all recorded uta-awase.[3]

Judgement

The judge was usually a poet of renown. During the Teijiin Poetry Contest the former emperor served as judge, and when one of his own offerings was matched against a superior poem by Ki no Tsurayuki, commented 'how can an imperial poem lose?', awarding himself a draw.[1] Fujiwara Shunzei served as judge some twenty-one times.[3] During the Poetry Contest in Six Hundred Rounds (六百番歌合) of 1192, he awarded victory to a poem with the line 'fields of grass', observing its reference to a previous work and commenting 'it is shocking for anyone to write poetry without knowing Genji'.[3] Judging another contest he wrote how, upon recital, there must be 'allure (en) and profundity (yūgen) ... an aura of its own that hovers about the poem much as a veil of haze among cherry blossoms, the belling of a stag before the autumn moon, the scent of springtime in the plum blossom, or the autumn rain in the crimson leaves upon the peak'.[7]

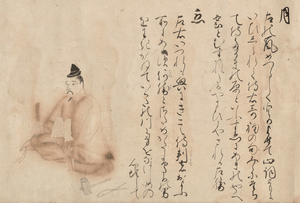

Utaawase-e

Utaawase-e (歌合絵) are illustrated records of actual poetry contests or depictions of imaginary contests such as between the Thirty-six Poetry Immortals.[8] The fourteenth-century emaki Tōhoku'in Poetry Contest among Persons of Various Occupations (東北院職人歌合絵巻) depicts a group of craftsmen who held a poetry contest in emulation of those of the nobility. With a sutra transcriber as judge, a physician, blacksmith, sword polisher, shrine maiden and fisherman competed against a master of Yin and Yang, court carpenter, founder, gambler and merchant, each composing two poems on the themes of the moon and love.[8][9]

Other offshoots

Jika-awase (自歌合), practised by the likes of poet-priest Saigyō, was a development in which the contestant 'played a kind of poetic chess with himself', selecting the topics, writing all the poems, and submitting the results to a judge for comment.[10][11] The Poetry Contest between Twelve Species (十二類歌合) is a satirical work of the early fifteenth century in which the Twelve Animals of the Zodiac hold a poetry competition on the themes of the moon and love; other animals headed by a stag and a badger gate-crash the gathering and the badger causes so much outrage that he barely escapes alive; disgraced, he retreats to a cave where he writes poems with a brush made of his own hair.[12]

See also

References

- McCullough, Helen Craig (1985). Brocade by Night: 'Kokin Waskashū' and the Court Style in Japanese Classical Poetry. Stanford University Press. pp. 240–254. ISBN 0-8047-1246-8.

- Konishi, Jin'ichi (1986). A History of Japanese Literature II: The Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. pp. 199–203. ISBN 0-691-10177-9.

- Keene, Donald (1999). Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from the Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century. Columbia University Press. pp. 648–652. ISBN 0-231-11441-9.

- "E-awase". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "Kai-awase". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Miner, Earl; Odagiri, Hiroko; Morrell, Robert E. (1985). The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature. Princeton University Press. pp. 290, 302. ISBN 0-691-00825-6.

- Royston, Clifton W. (1974). "Utaawase Judgments as Poetry Criticism". Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 34 (1): 99–108. doi:10.2307/2052411.

- "Utaawase-e". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "Touhoku'in Poetry Contest among Persons of Various Occupations, emaki". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- Miner, Earl (1968). An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford University Press. pp. 30–32. ISBN 0-8047-0636-0.

- Miner, Earl; Brower, Robert H. (1961). Japanese Court Poetry. Stanford University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 0-8047-1524-6.

- Ito, Setsuko (1982). "The Muse in Competition: Uta-awase Through the Ages". Monumenta Nipponica. Sophia University. 37 (2): 201–222 (209). doi:10.2307/2384242.