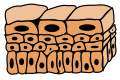

Transitional epithelium

Transitional epithelium is a type of stratified epithelium. This tissue consists of multiple layers of epithelial cells which can contract and expand in order to adapt to the degree of distension needed. Transitional epithelium lines the organs of the urinary system and is known here as urothelium. The bladder for example has a need for great distension.

| Transitional epithelium | |

|---|---|

Transitional epithelium | |

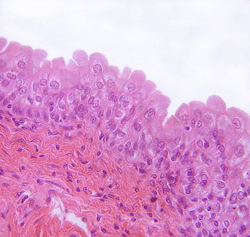

Transitional epithelium of the urinary bladder, known as urothelium. The rounded surface of the apical cells is a distinguishing characteristic of this type of epithelium. | |

| Details | |

| System | Urinary system |

| Identifiers | |

| TH | H2.00.02.0.02033 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

| This article is one of a series on |

| Epithelia |

|---|

| Squamous epithelial cell |

| Columnar epithelial cell |

| Cuboidal epithelial cell |

| Specialised epithelia |

|

| Other |

Structure

The appearance of transitional epithelium depends on the layers in which it resides. Cells of the basal layer are cuboidal, or cube-shaped, and columnar, or column-shaped, while the cells of the superficial layer vary in appearance depending on the degree of distension.[1] These cells appear to be cuboidal with a domed apex when the organ or the tube in which they reside is not stretched. When the organ or tube is stretched (e.g. when the bladder is filled with urine), the tissue compresses and the cells become stretched. When this happens, the cells flatten, and they appear to be squamous and irregular.

Cell layers

Transitional epithelium is made up of three types of cell layers: basal, intermediate, and superficial.[2] The basal layer fosters the epithelial stem cells in order to provide constant renewal of the epithelium.[3] These cells' cytoplasm is rich in tonofilaments and mitochondria; however, they contain few rough endoplasmic reticulum. The tonofilaments play a role in the attachment of the basal layer to the basement membrane via desmosomes.[4] The intermediate cell layer is highly proliferative and, therefore, provides for rapid cell regeneration in response to injury or infection of the organ or tube in which it resides.[3] These cells contain a prominent Golgi apparatus and an array of membrane-bound vesicles.[4] These function in the packaging and transport of proteins, such as keratin, to the superficial cell layer. The superficial cell layer, that which lines the lumen, is the only fully differentiated layer of the epithelium. It provides an impenetrable barrier between the lumen and the bloodstream, so as not to allow the bloodstream to reabsorb harmful wastes or pathogens.[3] All transitional epithelial cells are covered in microvilli and a fibrillar mucous coat.[2]

The epithelium contains many intimate and delicate connections to neural and connective tissue. These connections allow for communication to tell the cells to expand or contract. The superficial layer of transitional epithelium is connected to the basal layer via cellular projections, such as intermediate filaments protruding from the cellular membrane. These structural elements cause the epithelium to allow distension; however, these also cause the tissue to be relatively fragile and, therefore, difficult to study. All cells touch the basement membrane.

Cell membrane

Because of its importance in acting as an osmotic barrier between the contents of the urinary tract and the surrounding organs and tissues, transitional epithelium is relatively impermeable to water and salts. This impermeability is due to a highly keratinized cellular membrane synthesized in the Golgi apparatus.[5] The membrane is made up of a hexagonal lattice put together in the Golgi apparatus and implanted into the surface of the cell by reverse pinocytosis, a type of exocytosis.[6] The cells in the superficial layer of the transitional epithelium are highly differentiated, allowing for maintenance of this barrier membrane.[6] The basal layer of the epithelium is much less differentiated; however, it does act as a replacement source for more superficial layer.[6] While the Golgi complex is much less prominent in the cells of the basal layer, these cells are rich in cytoplasmic proteins that bundle together to form tonofibrils. These tonofibrils converge at hemidesmosomes to attach the cells at the basement membrane.[4]

Function

The transitional epithelium cells stretch readily in order to accommodate fluctuation of volume of the liquid in an organ (the distal part of the urethra becomes non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium in females; the part that lines the bottom of the tissue is called the basement membrane). Transitional epithelium also functions as a barrier between the lumen, or inside hollow space of the tract that it lines and the bloodstream. To help achieve this, the cells of transitional epithelium are connected by tight junctions, or virtually impenetrable junctions that seal together to the cellular membranes of neighboring cells. This barrier prevents re-absorption of toxic wastes and pathogens by the bloodstream.

Clinical significance

Urothelium is susceptible to carcinoma. Because the bladder is in contact with urine for extended periods, chemicals that become concentrated in the urine can cause bladder cancer. For example, cigarette smoking leads to the concentration of carcinogens in the urine and is a leading cause of bladder cancer. Aristolochic acid, a compound found in plants of the family Aristolochiaceae, also causes DNA mutations and is a cause of liver, urothelial and bladder cancers.[7] Occupational exposure to certain chemicals is also a risk factor for bladder cancer. This can include aromatic amines (aniline dye), polycytic aromatic hydrocarbons, and diesel engine exhaust.[8]

Carcinoma

Carcinoma is a type of cancer that occurs in epithelial cells. Transitional cell carcinoma is the leading type of bladder cancer, occurring in 9 out of 10 cases.[9] It is also the leading cause of cancer of the ureter, urethra, and urachus, and the second leading cause of cancer of the kidney. Transitional cell carcinoma can develop in two different ways. Should the transitional cell carcinoma grow toward the inner surface of the bladder via finger-like projections, it is known as papillary carcinoma. Otherwise, it is known as flat carcinoma.[9] Either form can transition from non-invasive to invasive by spreading into the muscle layers of the bladder. Transitional cell carcinoma is commonly multifocal, more than one tumor occurring at the time of diagnosis.

Transitional cell carcinoma can metastasize, or spread to other parts of the body via the surrounding tissues, the lymph system, and the bloodstream. It can spread to the tissues and fat surrounding the kidney, the fat surrounding the ureter, or, more progressively, lymph nodes and other organs, including bone. Common risk factors of transitional cell carcinoma include long-term misuse of pain medication, smoking, and exposure to chemicals used in the making of leather, plastic, textiles, and rubber.[10]

Transitional cell carcinoma patients have a variety of treatment options. These include nephroureterectomy, or the removal of kidney, ureter, and bladder cuff, and segmental resection of the ureter. This is an option only when the cancer is superficial and infects only the bottom third of the ureter. The procedure entails removing the segment of cancerous ureter and reattaching the end.[10] Patients with advanced bladder cancer or disease, also often look to bladder reconstruction as a treatment. Current methods of bladder reconstruction include the use of gastrointestinal tissue. However, while this method is effective in improving the function of the bladder, it can actually increases the risk of cancer, and can cause other complications, such as infections, urinary stones, and electrolyte imbalance. Therefore, other methods loom in the future. For example, current research paves the way for use of pluripotent stem cells to derive urothelium, as they are highly and indefinitely proliferative in vitro (i.e. outside of the body).[3]

Urothelial lesions

- Papillary urothelial lesions

- Papillary urothelial hyperplasia

- Urothelial papilloma

- Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP)

- Low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

- High-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

- Invasive urothelial carcinoma

- Flat urothelial lesions

- Reactive urothelial atypia

- Urothelial inverted papilloma

- Urothelial atypia of unknown significance

- Urothelial dysplasia

- Urothelial carcinoma in situ

- Invasive urothelial carcinoma

- Invasive urothelial carcinoma (NOS)

- Urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth pattern

- Urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation

- Urothelial carcinoma with villoglandular differentiation

- Urothelial carcinoma, micropapillary variant

- Urothelial carcinoma, lymphoepithelioma-like variant

- Urothelial carcinoma, clear cell (glycogen-rich) variant

- Urothelial carcinoma, lipoid cell variant

- Urothelial carcinoma with syncitiotrophoblastic giant cells

- Urothelial carcinoma with rhabdoid differentiation

- Urothelial carcinoma similar to giant cell tumor of bone

Gallery

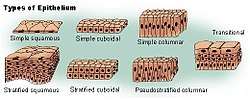

Types of epithelium

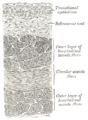

Types of epithelium Schematic view of transitional epithelium

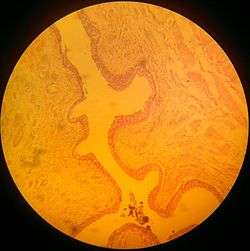

Schematic view of transitional epithelium Vertical section of bladder wall.

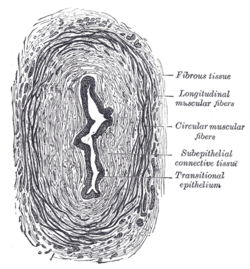

Vertical section of bladder wall. Transverse section of ureter.

Transverse section of ureter.

References

- Marieb, E., & Hoehn, K. (2013). Human anatomy & physiology (9th ed., pp. 122-124). Boston: Pearson.

- Monis, B., & Zambrano, D. (1968). Ultrastructure of transitional epithelium of man. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und Microscopical Anatomie, 87(1), 101-117.

- Osborn, S. L., & Kurzrock, E. A. (2015). Production of Urothelium from Pluripotent Stem Cells for Regenerative Applications. Current Urology Reports, 16(1), 1+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA390522720&v=2.1&u=clemsonu_main&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=bf6961c15c9b9523113dee93fd8df89c

- Hicks, R. (1965). The Fine Structure Of The Transitional Epithelium Of Rat Ureter. The Journal of Cell Biology, 26(1), 25-48. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://jcb.rupress.org/content/26/1/25.abstract

- Hicks, R. (1966). THE FUNCTION OF THE GOLGI COMPLEX IN TRANSITIONAL EPITHELIUM: Synthesis of the Thick Cell Membrane. The Journal of Cell Biology, 30(3), 623-643. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://jcb.rupress.org/content/30/3/623.abstract

- Firth, J. A., & Hicks, R. M. (1973). Interspecies variation in the fine structure and enzyme cytochemistry of mammalian transitional epithelium. Journal of Anatomy, 116(Pt 1), 31–43.

- Poon, Song Ling; Huang, Mi Ni; Choo, Yang; McPherson, John R.; Yu, Willie; Heng, Hong Lee; Gan, Anna; Myint, Swe Swe; Siew, Ee Yan; Ler, Lian Dee; Ng, Lay Guat; Weng, Wen-Hui; Chuang, Cheng-Keng; Yuen, John SP; Pang, See-Tong; Tan, Patrick; Teh, Bin Tean; Rozen, Steven G. (Dec 2015). "Mutation signatures implicate aristolochic acid in bladder cancer development". Genome Medicine. 7 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s13073-015-0161-3. PMC 4443665. PMID 26015808.

- "Bladder cancer risk factors". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- American Cancer Society. (2014). Bladder cancer. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/bladdercancer/detailedguide/bladder-cancer-what-is-bladder-cancer

- Transitional Cell Cancer. (2012, April 13). Retrieved December 14, 2014, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases_conditions/hic_Transitional_Cell_Cancer_of_Renal_Pelvis_and_Ureter

Bibliography

- Andersson, Karl-Erik (2011). Urinary Tract. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-16498-9.

External links

- Histology at utmb.edu

- Histology image: 36_02 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "ureter"

- Histology image: 37_02 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "urinary bladder"

- Anatomy Atlases - Microscopic Anatomy, plate 02.24 - "Transitional Epithelium", Ureter

- Histology at KUMC urinary-renal16 "ureter"

- www.urothelium.com is an online resource for information about Human Urothelium and the "Biomimetic Urothelium"

- Urothelium at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Histology at qmul.ac.uk

- Diagram at umich.edu

- Histology at wisc.edu