Upton's Hill

Upton's Hill is a geographic eminence located in western Arlington County, Virginia. Its summit rises to 410 feet (120 m) above sea level.[1]

Location

Upton's Hill straddles the border of Arlington County and Fairfax County, Virginia at 38.874279°N 77.146369°W. The hill is generally conical in shape with its summit lying astride Wilson Boulevard at its intersection with McKinley Street. A large water tower now occupies and marks its summit. The Southwest Number 8 boundary marker stone of the original District of Columbia is 100 feet (30.5 m) southeast of the base of the water tower (see Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia).[2][3]

A local stream called Four Mile Run defines the hill's northern and eastern extent. Munson's Hill (367 feet) is adjacent on its southeast, and Minor's Hill (459 feet) is adjacent on its northwest. Its location overlooks Arlington County and the city of Washington, D.C.

Name

The hill is occasionally identified as Upton Hill, and during the American Civil War many references to this and other slight variances were found in newspaper accounts and soldiers' letters home.

Upton's Hill takes its name from Charles H. Upton, a newspaper editor from Ohio who settled in the vicinity in 1836. Upton continued his newspaper activities from his home in Virginia for over three decades.[4]

By the time the Civil War opened in 1861, Upton had built a fine home atop the hill, on the northeast corner of today's Wilson Boulevard and McKinley Street. The home was surrounded by fruit orchards and was a working estate. (The home at this location now, while large and sitting on several acres of property, is of later construction and is not the same home.)

A Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority site, Upton Hill Regional Park, is located just downhill, bearing the hill's name, continuing its modern use as a place name.

History

Prehistoric and colonial eras

Upton's Hill was well known to local Native American inhabitants of Northern Virginia prior to European colonization. Four Mile Run was an important water source, and soapstone quarries upstream from the hill in Falls Church—also home to an Indian camp—testify to the stream's popularity. The valley of Four Mile Run at the base of Upton's Hill also afforded an excellent transportation corridor from the Potomac River to the headwaters of the Run, from which other connections to the Potomac River, such as Pimmit Run, could be utilized.

English colonists established Falls Church as a regional center of government and worship in 1733, choosing as its location a place that was approximately one day's horseback ride from the Potomac River. The hill and its residents were associated with Falls Church for many decades, as the village—1.5 miles distant—offered the nearest post office and mercantile stores.

Early statehood era

After the War of Independence and Virginia's statehood, commercial progress in the region was rapid. Virginia's interior and mountain areas were settled, and the promise of increasing commerce drove the founding of the Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad. The AL&H linked the port of Alexandria with Leesburg, and was intended to extend to Hampshire County, in what is now West Virginia.

The railroad opened in 1860. Its route lay along the valley of Four Mile Run, following it on its climb out of the Potomac River basin. Trains wound their way around the base of Upton's Hill. The nearest station stops were at Carlinville, east of the hill, and Falls Church, to its west.[5]

The Civil War

Although the American Civil War is often thought to have a distinct beginning, on Upton's Hill the disquiet began in 1859, with the unsuccessful raid by abolitionist John Brown on the U.S. armory at Harper's Ferry. This event caused area residents to begin considering the issue of slavery and states' rights in starkly contradictory terms. Many northerners lived at Falls Church and Upton's Hill-—including Charles Upton himself—-and their Southern neighbors now made them feel very unwelcome.[6]

Virginia held a statewide referendum to determine whether it would secede from the Union. At Falls Church the vote, for secession, was badly split, 44-26. The nature of each citizen's vote was verbally announced by the clerk of the polling station, and Northerners were physically intimidated by armed Southerners—-some of them officers in the new Confederate army—-who had gathered.

Charles Upton's son-in-law Hugh W. Throckmorton, who also lived on Upton's Hill, voted for Virginia to remain in the Union. Hugh accused his brother, John A. Throckmorton, of leading a band of 15-20 Southerners who intimidated Northern voters at Ball's Crossroads (now Ballston) and later at Falls Church. One of his men came to Upton's home that night looking for Hugh, who hid in a cornfield and fled at dawn's first light, not stopping until he crossed the safety of the Potomac River into Washington. He and John are thought never to have spoken again.[7]

During that same election on May 23, 1861, Charles Upton presented himself as a candidate for United States Congress. He was elected and seated in the House of Representatives. Several days later, however, his seating was challenged due the uncomfortable fact that Virginia had seceded from the Union. How could he represent Virginia, his opponents asked?

He couldn't, the House of Representatives found. Upton served until February 1862, after which President Abraham Lincoln appointed him United States consul to Switzerland, a post in which he served from 1863 through his death in Geneva in 1877.[8]

The Union Army's disastrous defeat during the First Battle of Manassas, in July 1861, changed the balance of power on Upton's Hill wildly. Union troops fled Manassas in a chaotic retreat, crossing the bridges into Washington. Confederate troops followed, occupying Upton's Hill and its neighbor to the southeast, Munson's Hill.

Upton sent his family to safety in Ohio, and moved into Washington. Confederate Army troops—led by his estranged son-in-law, John Throckmorton—occupied his fine home, seizing the furniture and also three slaves belonging to Hugh Throckmorton. The home's strategic location and heavy use by two armies caused it to suffer. "It was a beautiful house built out of white pine and right new," a Virginia soldier wrote in a letter home. "[Upton] had every convenience about his house that the heart could wish, but everything is torn to pieces," he observed, after sleeping for one night in the house while on picket duty.[9]

Events quickly shifted in the Union's favor as Confederate troops withdraw from the hill in late September 1861 and regrouped at Manassas. Union troops occupied the hill and Upton's home. Upton's Hill played a locally important role during the war, as the Union Army command used the home as its headquarters. The fruit trees were cut and a large masonry fort was constructed opposite the road (now Wilson Boulevard), at the hill's topmost point.

This fort was originally called Fort Upton but was later renamed Fort Ramsay. Several drawings, photographs and lithographs of it survive, and show an imposing structure fortified by multiple long-range cannon and manned accordingly. Surrounding the fort at various places on the hill were several large Union army encampments-—Camp Bliss, Camp Dupont, Camp Graham, Camp Keyes, Camp Marion, Camp Niagara, and Camp Upton. These replaced earlier Confederate fortifications.[10]

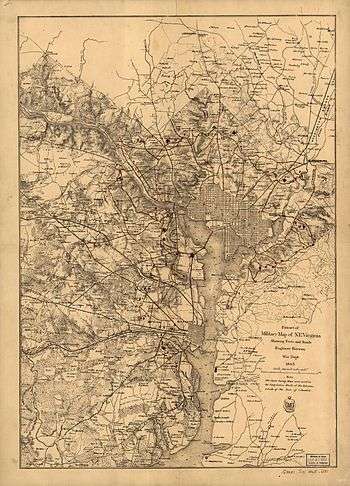

By the end of the war the Union Army built a tall wooden observation tower atop Congressman Upton's home, affording it line-of-sight communications with the Washington Monument and other observation and signal stations in the region. The hill was also connected to the military telegraph, at first to an army headquarters established in the mansion vacated by General Robert E. Lee (now called the Custis-Lee Mansion) in what is now Arlington National Cemetery, and later into a broader regional network.[11]

Battle Hymn of the Republic

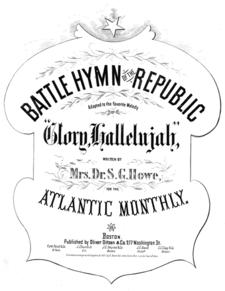

National history was made when one of the most famous songs of all time, Battle Hymn of the Republic, was composed as a result of events on Upton's Hill.

In November 1861, Julia Ward Howe rode from Washington in a carriage with the governor of Massachusetts and other family friends to Upton's Hill for a review of troops. The review was interrupted by reports of a firefight west of Falls Church between a possibly outgunned Union army cavalry and a larger Confederate force. The review ended quickly and soldiers left quickly for Falls Church.

Mrs. Howe was impressed by the review and by the night-time sights and sounds she encountered as she left it. The campfires and burnished arms all made an impression.

Riding in her carriage back to Washington, they made slow speed due to the soldiers marching before and behind them in the road. The soldiers were singing the popular tune, John Brown's Body ("John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave…"). A friend in the carriage suggested Howe, a sometime poet, should write new words for the tune. "I wish I might!," replied Mrs. Howe.

Early the next morning Mrs. Howe awoke in her hotel room in Washington and found she seemed to be composing verse. She "…found that the wished-for lines were arranging themselves in my brain. I lay quite still until the last verse had completed itself in my thoughts, then hastily arose, saying to myself, 'I shall lose this if I don't write it down immediately'."

Atlantic Monthly published Mrs. Howe's composition as a poem, set to the tune "John Brown's Body", in February 1862, calling it "Battle Hymn of the Republic". It was an immediate success, and was popular in the North for the rest of the war—and today.

As witnesses attested, "Battle Hymn" was composed as a result of the review on Upton's Hill. During later years confusion set in, as local historians mistakenly attributed the song's birth to a much larger and better known review held by President Abraham Lincoln at Bailey's Crossroads.[12] However, it is possible that Howe and others actually were viewing the Bailey's Crossroads troop review from Upton's Hill.[13]

Modern era

Upton Hill's summit is now home to a large water tower and an apartment complex. This is emblematic of the wave of residential and commercial development which swept the hill in the 1950s and 1960s. Some of the hill has been preserved as woods by the Upton Hill Regional Park, which also includes a pool, water park and batting cage at the top of the hill. A replica of a "Quaker gun"—a log painted black used to fool the enemy into believing the fort was defended with more guns—is also located in the park. The slopes are dotted with single-family homes. Seven Corners, a locally prominent shopping district, occupies neighboring Perkins Hill to the south and the shallow valley which separates the two.

References

- Falls Church quad, U.S. Geological Survey map.

- "SW8". Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia. boundarystones.org. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- "Southwest No. 8 Boundary Marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Bradley E. Gernand. A Virginia Village Goes to War--Falls Church During the Civil War. Virginia Beach: The Donning Company, 2002, p. 27.

- AL&H Railroad Company timetable republished in Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, p. 13.

- Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, p. 11.

- Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, pp. 25-27.

- Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, p. 27.

- Letter by C.J. Winston, dated September 4, 1861, as cited by Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, p. 65.

- Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, pp. 38, 41-42, 48, 49-50, 108, 123, 135, 137, 150, 152-153, 155, 157.

- Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, pp. 111, 116, 154, 199.

- Letters and memoirs by Julia Ward Howe; a book later published by her daughter; and a memoir by the assistant secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, cited by Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, pp. 137-139.

- http://www.friendsofgettysburg.org/FriendsofGettysburg/TheGreatTaskBeforeUs/TheGreatTaskBeforeUsDetails/tabid/99/ItemId/371/November-20th-2011-Grand-Review-at-Bailey-s-Crossroads.aspx shows the likely perspective of an artist who sketched the review as Upton's Hill.