Centreville Military Railroad

The Centreville Military Railroad was a 5.5-mile (8.9 km) spur running from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad east of Manassas Junction across Bull Run and up the south side of the Centreville Plateau. Built by the Confederate States Army between November 1861 and February 1862, it was the first exclusively military railroad.[1] Ultimately, the Centreville Military Railroad reached a point near a modern McDonald's restaurant on Virginia State Route 28, south of the modern junction with U.S. Route 29 in Virginia.

Background

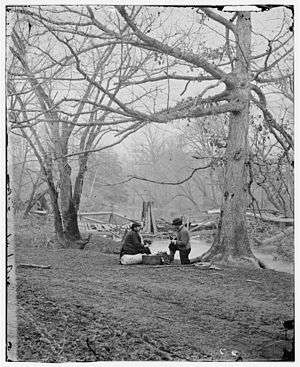

Centreville encampment

Gen Joseph E. Johnston faced a Federal force superior in size, while his own Confederate Army of the Potomac[1] was spread thinly across central Fairfax County, Virginia, at Minor’s Hill, Flint Hill, Pohick, Accotink, Annandale, Munson’s Hill and Mason’s Hill. To prepare a better defensible position, he concentrated his troops on the Centreville Plateau, the high ground between Little Rocky Run and Bull Run along the western edge of Fairfax County, with his main supply base at the Manassas Junction in his rear in Prince William County, Virginia. The Centreville Plateau is located about six miles (9.7 km) north of Manassas Junction (modern Manassas, Virginia). The Confederates built an elaborate series of connected forts and military positions, and the Confederate cavalry and advanced pickets and vedettes controlled the countryside as far east as Fairfax Courthouse. The army went into camp and built winter quarters in Centreville which were protected by strong fortifications. The logistics of supplying 40,000 Confederate troops on the front lines grew worse with wet weather in October, so they withdrew even more into Centreville. Behind the lines, warehouses were built at Manassas Junction. Chapman (Beverly) Mill in Thoroughfare Gap, at the border of Prince William and Fauquier counties, also served as a supply depot. Over one million pounds of meat were stored there in the winter of 1861-62 to feed the Confederate Army of the Potomac.[2]

Logistics problems

As winter approached the wagons hauling supplies from Manassas Junction up the old Centreville Road turned the roadway into muddy mire.[1] By October 19, 1861, the Centreville Road had been planked to help alleviate this problem, but with no success. By early November, Quartermaster Major Albert Marle discovered that the ox teams being used to haul the wagons were eating too much fodder to make the logistics operation practical.[3]

Construction

The idea of building a railroad, using spare and captured parts, became a viable option to ox carts and wagon teams on the muddy Centreville Road.[1] However, on November 7, 1861, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (O&ARR) disapproved a request to using any of their rails to build such a line.[1] Private McClellan of the 9th Alabama Infantry Regiment commented in his diary on November 23 that 50,000 men were working on a six-mile (9.7 km) railroad in shifts of six hours per day, causing them to have no time for working on winter huts. By November 30, 1861 newspaper articles reported two months would be necessary to build the planned railroad.[1][4]

Construction began in December from the O&ARR tracks at Manassas Junction.[1][5] On December 14, 1861, the newspapers reported that the new line was fully surveyed, was being leveled and that the line would run four miles (6.4 km) to Bull Run and then two miles (3.2 km) beyond that to the rear of the army. The rails, by order of Captain Thomas R. Sharp, were brought in from warehouses where they were being held in storage in Winchester, Virginia by wagon down to Strasburg, Virginia, and then by rail car to the Manassas Junction. "It is no mystery that the iron for the track came from the South's one unfailing source of supply in 1861, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad."[6] A deserter from the 6th Louisiana Infantry, who left Centreville on January 7, 1862 reported that 300 men were working on the railroad project.[1] The Pinkerton National Detective Agency confirmed on January 27, 1862, based on the report of a deserter that the railroad construction was in progress.[4]

By February 5, 1862 the construction was still proceeding, but no ballast was being used, as is typically needed for drainage and stability of rail beds, and the ties were being spaced a twice the normal spread. It is estimated that the railroad was probably not finished before the first week of February, 1862, but was in successful operation as early as February 17, 1862.[4]

Design

The rail line designed used long lazy-S curves, paralleling west along the old Centreville Road.[7] It ran four miles (6.4 km), crossing Liberia Plantation, then across a new special trestle bridge constructed on Bull Run. It ran another one and a half miles (2.4 km) north of Bull Run and finished in a terminus on level fields at Mertoff Farm. The gauge is presumed to be 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) narrow gauge, matching the O&ARR and Manassas Gap Railroad, which it spurred from, and used T-rail acquired from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad during raids.[3]

Operation

Trains, pressed into service from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad[7] ran on the line from Manassas Junction from about the second week of February, 1862 until March 11, 1862 when Confederate forces withdrew southward.

Supply operations begin

While the railroad was exclusively designed only for resupply of the army, on a temporary and light track, an issue soon arose about the transportation of heavier loads of sick soldiers. Initially the locomotives used were under-powered for hauling large loads of sick soldiers and General Johnston did not allow use of the trains for transporting the sick. Later, larger locomotives were brought in and Johnston changed his mind, allowing evacuations of the sick south to the large Confederate hospital located in Charlottesville, Virginia. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad company disagreed with Johnston’s decision and actions, but were over-ridden by order of Johnston to Major Barber to transport the sick all the way to Charlottesville.

On March 1, 1862 Major Barber issued orders to Captain Thomas Sharp regulating the operations of the railroad, specifying the types of loading for sick, for lady passengers, supplies, baggage, and requiring daily reports.

Federal reaction

Federal soldiers examining the earthworks from a distance came to believe the defenses at Centreville were virtually impregnable. The Confederate defense line along Bull Run appeared too strong to Major General George B. McClellan, the Federal officer charged with the responsibility of capturing Richmond after Major General Irvin McDowell had failed in July, 1861. McClellan identified another route to Richmond that would bypass the Bull Run defenses - sail the Union Army down the Potomac River to Fortress Monroe, then march up the Peninsula past Williamsburg to Richmond.[4]

Operations end

The operation of the railroad was very short lived, as General Johnston decided on March 9, 1862 to abandon his defensive positions on the Centreville Plateau and move south of the Rappahannock River[8] to counter Major General McClellan’s movements to Hampton Roads, Virginia. On March 11, 1862, the Confederates quickly abandoned their positions, tore up as much track as possible, leaving much of the rail lying in place, and destroyed the trestle bridge across Bull Run. Federal troops entered and occupied the area on that same day[4] and decided to rip up and "use the slightly worn rails for repairs elsewhere in Virginia."[8]

Aftermath

On May 7, 1862, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&ORR) began trying to recover property from the abandoned rail line after making an inspection trip on April 30. The B&ORR claimed that their rails were uniquely identifiable, and knew they had been stolen during Virginia Militia and Confederate operations as part of the Great Train Raid of 1861. However the Federal quartermaster made a decision on May 20 to take 6.5 miles (10.5 km) of inventoried and captured Confederate rail from this railroad and use it on other needed Union Army rail projects. The following day, B&ORR President John W. Garrett send a letter of protest regarding the intended Federal re-use, having found out that the Union Army planned to use the rails to repair the Manassas Gap Railroad for help in resupplying Major General Nathaniel Prentice Banks in the Shenandoah Valley.[4][7]

Quickly taking action, the B&ORR provided a full report with a detailed description of their property on May 24. The Union Army replied on June 7 that it intended to keep and use the rails, and President Garrett again responded on June 9 that he absolutely needed the rails for the more serious need of repairing the B&O rail line to restore services there, which were more vital to overall Union Army needs. The Union Army finally complied with Garrett’s request and by the end of July 1862 the rails of the Centreville Military Railroad were all returned to the original rightful owners, the B&O Railroad.[4]

"Once its rails were removed virtually all traces of the world's first military railroad were speedily obliterated by undergrowth. For all but a very few its brief existence was soon forgotten."[7]

Notes

- Johnston, p.35

- Candendquist, CWEA Tour

- Candenquist

- Candenquist, CWEA Tour

- Netherton p. 68

- Johnston, pp.35-36

- Johnston, p.36

- Johnston, p. 36

References

- Candenquist, Arthur, The Great Train Robbery - or The Confederates Gather Steam, Winchester, Virginia, CWEA, August 2008, 17-page pamphlet for historical field tours through the Civil War Education Association

- Hanson, Joseph Mills, Bull Run Remembers: The History, Traditions, and Landmarks of the Manassas (Bull Run) Campaign Before Washington, 1861-1862, National Capitol Publishers, Inc., 1957 ISBN B0007DRPR6

- Johnston II, Angus James, Virginia Railroads in the Civil War, University of North Carolina Press for the Virginia Historical Society, 1961.

- Netherton, Ross D., In the Path of History: Virginia between the Rappahannock and the Potomac, Ruth Preston Rose, 1986. ISBN 0-914927-46-9