United States Lake Survey

The United States Lake Survey (USLS) was a hydrographic survey for the Great Lakes, New York Barge Canal, Lake Champlain and the Boundary Waters of the Canada–United States border between Minnesota and Ontario. The Survey's activities began on 31 March 1841, with the goal of surveying the Great Lakes. The Lake Survey was created within the United States Army Topographical Engineers (later the United States Army Corps of Engineers). Like the Commerce Department's Coast and Geodetic Survey, the Lake Survey had responsibility for the preparation and publication of nautical charts and other navigational aids. By 1882, the Survey had completed the original Congressional mandate, producing 76 charts, then disbanded. By 1901, the original survey and charting products required revision. The Lake Survey was reconstituted and its mission expanded. In addition to traditional survey, charting, and navigation information responsibilities, the Lake Survey was also responsible for studies on lake levels and associated river flow.

.png)

Early history (1841–56)

The United States Lakes Survey was created on 31 March 1841 by an act of Congress, appropriating $15,000 for a United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers led survey of the Great Lakes.[1] William G. Williams was appointed the first commander of the survey. He was assisted by Howard Stansbury, James H. Simpson, Joseph E. Johnston and I. Carle Woodruff. They were headquartered at the mouth of the Buffalo River. In the first summer, a detailed topographical survey of Mackinac Island was completed, reconnaissance surveys in the northern part of Lake Michigan were made and a site for a baseline near the entrance to Green Bay was selected and partly cleared.[2]

The first four years of the survey largely dealt with the baseline at Green Bay, and building triangulation stations. Surveying work was additionally done on Lakes Michigan, St. Clair, and Erie, and at the Straits of Mackinac. To conduct hydrographic surveys, in 1843, an iron steamer named the Abert (after John James Abert) was built for the survey. Flaws in the ship's design were soon discovered, and it was overhauled and renamed Surveyor in early 1845. By the end of 1845, all harbors besides those in Lake Superior had been surveyed.[3]

James Kearney replaced Williams in 1845, relocating the survey to Detroit. Work was temporarily halted for most of the Mexican–American War. After the war, work resumed and the west end of Lake Erie was completed in 1849. John N. Macomb took command of the lake survey in 1851. It greatly increased in size and appropriations.[4] It published its first charts in 1852–covering all of Lake Erie.[5] During the 1852–55 seasons, the areas surveyed by the Lake Survey included the Straits of Mackinac and the approaches 30 miles (48 km) to 40 miles (64 km) either side of Mackinac Island, part of the north end of Lake Michigan, all of the St. Marys River, and a few harbors on Lake Superior. As a result of this work the Lake Survey published three new charts. A second steamer, the Jefferson Davis (after Jefferson Davis) was launched in 1856, and soon renamed Search.[6]

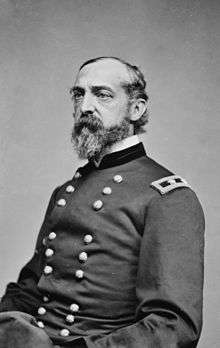

Meade years (1857–61)

On 20 May 1857, Kearney was replaced by George Meade. Meade completed the survey of Lake Huron during the 1857–59 seasons and completed the survey of Saginaw Bay as well. He surveyed the Fox and Manitou Islands, and Grand and Little Traverse Bays. The Lake Survey completed a few local harbor surveys on Lake Superior by 1859 and began a general survey of the western end of that lake in 1861. He oversaw a dramatic expansion in the survey, including the construction of an observatory in Detroit and the first systematic recording of lake water levels.[7][8]

In 1859, a network of 19 meteorological stations around the Lakes were completed.[9] From 1858 through 1861, the federal appropriations for the Lake Survey grew to $75,000 annually. Meade would later write that he considered his early work on the lakes survey as among the most important duties of his extensive career. Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, he offered his services to the Union Army.[8]

Completion of original survey

James D. Graham replaced Meade in 1861, and led the survey through much of the Civil War, during which it was the only active topographical field office still operating. During the war, the department still increased, with appropriations rising to $125,000 in 1865.[10][11] Surveys were completed of Portage Entry on Keweenaw Bay, and the waters of the Keweenaw Waterway. In 1863, the survey formally became part of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[12] In 1864, William F. Reynolds replaced Graham.[10] As a result of the work on Lake Superior, eight new charts of that lake were published between 1865 and 1873. The charts were given away for free to mariners. Between October 1861 and October 1865, 15,210 navigational charts had been distributed to Great Lakes mariners, bringing the number issued since 1852 to 30,120. In 1869, distribution was further expanded as the Lake Survey was authorized to sell surplus charts for the first time.[13]

In the spring of 1867, a program of river flow measurement was created. Three years later, Reynolds was removed from his command. Cyrus B. Comstock replaced him. Comstock oversaw the completion of a larger observatory, the publishing of a first complete set of charts. The surveys of Lake Michigan were completed in 1874, Lake Superior in 1874, Lake Ontario in 1875 and Lake Erie in 1877. Lake St. Clair and Lake Champlain were completed in 1871. During the summer of 1873 and the following winter, a complete survey of the city of Detroit and the Detroit River was made. A survey of the St. Lawrence began during 1871 at the boundary line near St. Regis, New York, and ended at the head of the river on Lake Ontario in 1873. The survey work on the Mississippi, for which Congress appropriated $16,000 in 1876, began in Cairo, Illinois, and was completed at the mouth of the Arkansas River in 1879.[14]

The survey was officially completed in 1882, when the original mandate was completed, with 76 charts produced.[5] A historian at the time said:

It is probable that thousands of lives and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of property would be lost annually except for the information afforded through the Lake Survey. In fact, the navigation of the lakes would of necessity almost entirely cease but for the information thus supplied.

— Silas Farmer[15]

Re-establishment

In the decade after the original survey was ended, it became clear that the charts were not sufficient; for example, since the deepest draft vessels used in the Great Lakes in the mid-late 1800s drew only 12 feet (3.7 m) of water, the Survey's charts only showed depths of 18 feet (5.5 m) or less.[5] Though work on charts had continued in the time between the survey, the Lake Survey was officially re-formed on 9 January 1901,[16] having been part of the Detroit office of the Army Corps of Engineers since 1889.[1]

For the first time, the Survey published maps in color, and the Great Lakes Bulletin. The charts and bulletin were increasingly requested. The Survey collaborated with the United States Geological Survey, and resumed field surveys, resurveying Apostle Islands and vicinity on Lake Superior, the St. Lawrence River, and northern Lake Michigan and the Straits of Mackinac. Several more steamers were acquired to cope with increased workload. Areas that needed the most work were identified, being the east end of Lake Superior and the waters around Isle Royale; the southern end of Lake Michigan; the Straits of Mackinac; both ends of Lake Erie; and the east end of Lake Ontario including the head of the St. Lawrence River. In addition, along the shores of the Lakes in inadequately surveyed areas, sounding and sweeping were necessary. Specifically, these areas were the south shore of Lake Superior, Grand and Little Traverse Bays, the Keweenaw Peninsula, the west shore of Lake Michigan, and the south and west shores of Lake Huron. It worked on those projects for the next 30 years.[17]

The Survey worked on several water diversion projects, including that undertaken by the Niagara Falls Hydraulic Power and Manufacturing Company (in 1906) and water diversion into the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (1912), both times it was called upon to study the effect the diversion would have.[18] On 4 March 1911, its jurisdiction was expanded to include the New York State Barge Canal System and the areas between Lake Superior and Lake of the Woods, which included the Boundary Waters.[1] After several other expansions, in 1914, it became responsible for "an inland waterway system extending nearly halfway across the continental United States". During World War I, the Lake Survey printed recruiting posters, charts and maps for the areas outside the Great Lakes, and other items requested by the War Department. By the end of 1918, it had printed and distributed 573,000 charts of the Great Lakes. Mason Patrick was one of the commanders during this time.[18]

Work continued throughout the 1920s. By 1922, the Lake Survey was distributing 123 different charts. The Superior Shoal was discovered. Funding shrunk at the onset of the Great Depression, but aerial photography was introduced. In 1936, a total of over 1 million charts was reached. To support new equipment and new surveys, funding for the Lake Survey was expanded in the 1930s. The project begun in 1907 was completed, and resurveying began in 1937.[19]

World War II and later work

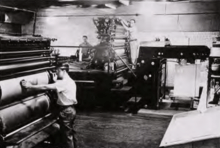

Upon the outbreak of World War II, the survey began working in various war capacities. It published a "Submarine Training Chart of Upper Lake Michigan" pamphlet. The Lake Survey, with its cartographic and lithographic specialists, directed a major portion of the military's mapping activity. It took over and consolidated the former WPA cartographic units in New York, Chicago, and Detroit on 1 June 1942. It published 370 tons of maps, producing 8,109 different charts and maps, printing and distributing 9,190,000 copies to the armed forces.[20] It was also responsible for Mosaic Mapping Unit in Detroit and the Military Grid Unit at New York City, accounting for another 885 separate mosaic maps with more than 3,128,000 copies being printed. The survey received the Army-Navy "E" Award for its work.[20]

After World War II, work on the survey continued. During the shipping season of 1948, it began work on an experimental "radar chart". The mapping unit also continued to do some work for the War Department, particularly during the Korean War. Electronic surveying methods were also tested.[21] The Survey grew further in 1962 with the establishment of the Great Lakes Research Center. The Center conducted strong programs in coastal engineering and water resources.[5] It was involved heavily in the building of the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Growth of the survey continued, reaching over two million dollars of appropriations in 1968.[21] By Reorganization Plan Number 4 of 1970, effective October 3, 1970, Lake Survey Office transferred to newly established National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), where it was redesignated the Lake Survey Center and assigned to the National Ocean Survey. Various activities of the Lake Survey Center transferred to other NOAA organizations, 1974–76. The Lake Survey Center was abolished, June 30, 1976.[1]

References

- "Records of the office of the Chief of Engineers [OCE]". National Archives. 2016-08-15. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 14, 19–23.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 23–28.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 29–31.

- "NOAA History – United States Lake Survey". National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 35–36.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 37–41.

- Person 2010, p. 44.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 47–62.

- Person 2010, p. 46.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 43–44, 46.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 43–44.

- Woodford 1991, p. 45.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 47–61.

- 56. Silas Farmer, History of Detroit and Wayne County and Early Michigan, 3rd ed., (Detroit: Farmer & Co., 1890), p. 918.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 47–83.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 85–100.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 102–108.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 114, 121–131.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 137–143.

- Woodford 1991, pp. 148–186.

Sources

- Person, Gustav J. (2010). Captain George G. Meade and the United States Lake Survey (PDF). United States Army.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodford, Arthur M. (1991). Charting the Inland Seas: A History of the U.S. Lake Survey (PDF). Detroit, Michigan: United States Army.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)